27 Jan 2026

LXer Linux News

LXer Linux News

GParted 1.8 Partition Editor Improves FAT Handling

GParted 1.8 partition editor is out with multiple crash fixes, improved FAT handling, and safer file system copying.

27 Jan 2026 8:38am GMT

How one developer used Claude to build a memory-safe extension of C

Robin Rowe talks about coding, programming education, and China in the age of AIfeature TrapC, a memory-safe version of the C programming language, is almost ready for testing.…

27 Jan 2026 7:06am GMT

AMD Radeon Linux Driver Introduces Low-Latency Video Decode Option

AMD's RadeonSI Gallium3D driver for next quarter's Mesa 26.1 release is introducing a new low-latency video decode mode. This lower-latency video decoding comes with a trade-off of increased GPU power consumption...

27 Jan 2026 5:35am GMT

Drupal.org aggregator

Drupal.org aggregator

ImageX: Mastering Robots.txt: An Essential SEO Tool for Your Drupal Site

When we think of robots, we often picture shiny machines whirring around in sci‑fi movies, or perhaps we think of something that is gradually becoming part of our reality. But not all robots are mechanical. In the world of SEO, search engine bots are tiny robots exploring your Drupal website, and with the right guidance, you can make sure they stick to the paths that matter.

27 Jan 2026 4:29am GMT

26 Jan 2026

Drupal.org aggregator

Drupal.org aggregator

drunomics: drunomics joins the Drupal AI Initiative as Silver Maker

drunomics joins the Drupal AI Initiative as Silver Maker

wolfgang.ziegler

26 Jan 2026 8:50pm GMT

Talking Drupal: Talking Drupal #537 - Orchestration

Today we are talking about Integrations into Drupal, Automation, and Drupal with Orchestration with guest Jürgen Haas. We'll also cover CRM as our module of the week.

For show notes visit: https://www.talkingDrupal.com/537

Topics

- Understanding Orchestration

- Orchestration in Drupal

- Introduction to Orchestration Services

- Drupal's Role in Orchestration

- Flexibility in Integration

- Orchestration Module in Drupal

- Active Pieces and Open Source Integration

- Security Considerations in Orchestration

- Future of Orchestration in Drupal

- Getting Involved with Orchestration

Resources

- Orchestration

- N8N

- Drupal as an application

- Tools

Guests

Jürgen Haas - lakedrops.com jurgenhaas

Hosts

Nic Laflin - nLighteneddevelopment.com nicxvan John Picozzi - epam.com johnpicozzi

MOTW Correspondent

Martin Anderson-Clutz - mandclu.com mandclu

- Brief description:

- Have you ever wanted a Drupal-native way to store, manage, and interact with people who might not all be registered users? There's a module for that.

- Module name/project name:

- Brief history

- How old: created in Apr 2007 by Allie Micka, but the Steve Ayers aka bluegeek9 took over the namespace

- Versions available: 1.0.0-beta2, which works with Drupal 11.1 or newer

- Maintainership

- Actively maintained, latest release just a day ago

- Security coverage: opted in, but needs a stable release

- Test coverage

- Number of open issues: 73 open issues, but all bugs have been marked as fixed

- Usage stats:

- 10 sites

- Module features and usage

- Listeners may remember some mention of the CRM module in the conversation about the Member Platform initiative back in episode 512

- As a reminder, something other than standard Drupal user accounts is useful for working with contact information for people where you may not have all the criteria necessary for a Drupal user account, for example an email address. Also, a dedicated system can make it easier to model relationships between contacts, and provide additional capabilities.

- It's worth noting that this module defines CRM as Contact Relationship Management, not assuming that the data is associated with "customers" or "constituents" as some other solutions do

- At its heart, CRM defines three new entity types: contacts, contact methods, and relationships. Each of these can have fieldable bundles, and provides some default examples: Person, Household, and Organization for contacts; Address, Email, and Telephone for contact methods; and Head of household, Spouse, Employee, and Member for relationships

- Out of the box CRM includes integrations with other popular modules like Group and Context, in addition to a variety of Drupal core systems like views and search

- As previously mentioned CRM is intended to be the foundational data layer of the Member Platform, but is also a key element of the Open Knowledge distribution, meant to allow using Drupal as a collaborative knowledge base and learning platform

26 Jan 2026 7:00pm GMT

Planet Python

Planet Python

Real Python: GeoPandas Basics: Maps, Projections, and Spatial Joins

GeoPandas extends pandas to make working with geospatial data in Python intuitive and powerful. If you're looking to do geospatial tasks in Python and want a library with a pandas-like API, then GeoPandas is an excellent choice. This tutorial shows you how to accomplish four common geospatial tasks: reading in data, mapping it, applying a projection, and doing a spatial join.

By the end of this tutorial, you'll understand that:

- GeoPandas extends pandas with support for spatial data. This data typically lives in a

geometrycolumn and allows spatial operations such as projections and spatial joins, while Folium focuses on richer interactive web maps after data preparation. - You inspect CRS with

.crsand reproject data using.to_crs()with an authority code likeEPSG:4326orESRI:54009. - A geographic CRS stores longitude and latitude in degrees, while a projected CRS uses linear units like meters or feet for area and distance calculations.

- Spatial joins use

.sjoin()with predicates like"within"or"intersects", and both inputs must share the same CRS or the relationships will be computed incorrectly.

Here's how GeoPandas compares with alternative libraries:

| Use Case | Pick pandas | Pick Folium | Pick GeoPandas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tabular data analysis | ✅ | - | ✅ |

| Mapping | - | ✅ | ✅ |

| Projections, spatial joins | - | - | ✅ |

GeoPandas builds on pandas by adding support for geospatial data and operations like projections and spatial joins. It also includes tools for creating maps. Folium complements this by focusing on interactive, web-based maps that you can customize more deeply.

Get Your Code: Click here to download the free sample code for learning how to work with GeoPandas maps, projections, and spatial joins.

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive "GeoPandas Basics: Maps, Projections, and Spatial Joins" quiz. You'll receive a score upon completion to help you track your learning progress:

Interactive Quiz

GeoPandas Basics: Maps, Projections, and Spatial JoinsTest GeoPandas basics for reading, mapping, projecting, and spatial joins to handle geospatial data confidently.

Getting Started With GeoPandas

You'll first prepare your environment and load a small dataset that you'll use throughout the tutorial. In the next two subsections, you'll install the necessary packages and read in a sample dataset of New York City borough boundaries. This gives you a concrete GeoDataFrame to explore as you learn the core concepts.

Installing GeoPandas

This tutorial uses two packages: geopandas for working with geographic data and geodatasets for loading sample data. It's a good idea to install these packages inside a virtual environment so your project stays isolated from the rest of your system and you can manage its dependencies cleanly.

Once your virtual environment is active, you can install both packages with pip:

$ python -m pip install "geopandas[all]" geodatasets

Using the [all] option ensures you have everything needed for reading data, transforming coordinate systems, and creating plots. For most readers, this will work out of the box.

If you do run into installation issues, the project's maintainers provide alternative installation options on the official installation page.

Reading in Data

Most geospatial datasets come in GeoJSON or shapefile format. The read_file() function can read both, and it accepts either a local file path or a URL.

In the example below, you'll use read_file() to load the New York City Borough Boundaries (NYBB) dataset. The geodatasets package provides a convenient path to this dataset, so you don't need to download anything manually. You'll also drop unnecessary columns:

>>> import geopandas as gpd

>>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

>>> from geodatasets import get_path

>>> path_to_data = get_path("nybb")

>>> nybb = gpd.read_file(path_to_data)

>>> nybb = nybb[["BoroName", "Shape_Area", "geometry"]]

>>> nybb

BoroName Shape_Area geometry

0 Staten Island 1.623820e+09 MULTIPOLYGON (((970217.022 145643.332, ....

1 Queens 3.045213e+09 MULTIPOLYGON (((1029606.077 156073.814, ...

2 Brooklyn 1.937479e+09 MULTIPOLYGON (((1021176.479 151374.797, ...

3 Manhattan 6.364715e+08 MULTIPOLYGON (((981219.056 188655.316, ....

4 Bronx 1.186925e+09 MULTIPOLYGON (((1012821.806 229228.265, ...

>>> type(nybb)

<class 'geopandas.geodataframe.GeoDataFrame'>

>>> type(nybb["geometry"])

<class 'geopandas.geoseries.GeoSeries'>

nybb is a GeoDataFrame. A GeoDataFrame has rows, columns, and all the methods of a pandas DataFrame. The difference is that it typically includes a special geometry column, which stores geographic shapes instead of plain numbers or text.

The geometry column is a GeoSeries. It behaves like a normal pandas Series, but its values are spatial objects that you can map and run spatial queries against. In the nybb dataset, each borough's geometry is a MultiPolygon-a shape made of several polygons-because every borough consists of multiple islands. Soon you'll use these geometries to make maps and run spatial operations, such as finding which borough a point falls inside.

Mapping Data

Once you've loaded a GeoDataFrame, one of the quickest ways to understand your data is to visualize it. In this section, you'll learn how to create both static and interactive maps. This allows you to inspect shapes, spot patterns, and confirm that your geometries look the way you expect.

Creating Static Maps

Read the full article at https://realpython.com/geopandas/ »

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 - Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

26 Jan 2026 2:00pm GMT

Kushal Das: replyfast a python module for signal

replyfast is a Python module to receive and send messages on Signal.

You can install it via

python3 -m pip install replyfast

or

uv pip install replyfast

I have to add Windows builds to CI though.

I have a script to help you to register as a device, and then you can send and receive messages.

I have a demo bot which shows both sending and rreceiving messages, and also how to schedule work following the crontab syntaxt.

scheduler.register(

"*/5 * * * *",

send_disk_usage,

args=(client,),

name="disk-usage",

)

This is all possible due to the presage library written in Rust.

26 Jan 2026 12:16pm GMT

Real Python: Quiz: GeoPandas Basics: Maps, Projections, and Spatial Joins

In this quiz, you'll test your understanding of GeoPandas.

You'll review coordinate reference systems, GeoDataFrames, interactive maps, and spatial joins with .sjoin(). You'll also explore how projections affect maps and learn best practices for working with geospatial data.

This quiz helps you confirm that you can prepare, visualize, and analyze geospatial data accurately using GeoPandas.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 - Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

26 Jan 2026 12:00pm GMT

Planet Lisp

Planet Lisp

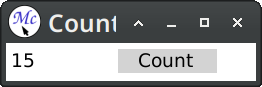

TurtleWare: McCLIM and 7GUIs - Part 1: The Counter

Table of Contents

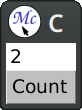

For the last two months I've been polishing the upcoming release of McCLIM. The most notable change is the rewriting of the input editing and accepting-values abstractions. As it happens, I got tired of it, so as a breather I've decided to tackle something I had in mind for some time to improve the McCLIM manual - namely the 7GUIs: A GUI Programming Benchmark.

This challenge presents seven distinct tasks commonly found in graphical interface requirements. In this post I'll address the first challenge - The Counter. It is a fairly easy task, a warm-up of sorts. The description states:

Challenge: Understanding the basic ideas of a language/toolkit.

The task is to build a frame containing a label or read-only textfield T and a button B. Initially, the value in T is "0" and each click of B increases the value in T by one.

Counter serves as a gentle introduction to the basics of the language, paradigm and toolkit for one of the simplest GUI applications imaginable. Thus, Counter reveals the required scaffolding and how the very basic features work together to build a GUI application. A good solution will have almost no scaffolding.

In this first post, to make things more interesting, I'll solve it in two ways:

- using contemporary abstractions like layouts and gadgets

- using CLIM-specific abstractions like presentations and translators

In CLIM it is possible to mix both paradigms for defining graphical interfaces. Layouts and gadgets are predefined components that are easy to use, while using application streams enables a high degree of flexibility and composability.

First, we define a package shared by both versions:

(eval-when (:compile-toplevel :load-toplevel :execute)

(unless (member :mcclim *features*)

(ql:quickload "mcclim")))

(defpackage "EU.TURTLEWARE.7GUIS/TASK1"

(:use "CLIM-LISP" "CLIM" "CLIM-EXTENSIONS")

(:export "COUNTER-V1" "COUNTER-V2"))

(in-package "EU.TURTLEWARE.7GUIS/TASK1")

Note that "CLIM-EXTENSIONS" package is McCLIM-specific.

Version 1: Using Gadgets and Layouts

Assuming that we are interested only in the functionality and we are willing to ignore the visual aspect of the program, the definition will look like this:

(define-application-frame counter-v1 ()

((value :initform 0 :accessor value))

(:panes

;; v type v initarg

(tfield :label :label (princ-to-string (value *application-frame*))

:background +white+)

(button :push-button :label "Count"

:activate-callback (lambda (gadget)

(declare (ignore gadget))

(with-application-frame (frame)

(incf (value frame))

(setf (label-pane-label (find-pane-named frame 'tfield))

(princ-to-string (value frame)))))))

(:layouts (default (vertically () tfield button))))

;;; Start the application (if not already running).

;; (find-application-frame 'counter-v1)

The macro define-application-frame is like defclass with additional clauses. In our program we store the current value as a slot with an accessor.

The clause :panes is responsible for defining named panes (sub-windows). The first element is the pane name, then we specify its type, and finally we specify initargs for it. Panes are created in a dynamic context where the application frame is already bound to *application-frame*, so we can use it there.

The clause :layouts allows us to arrange panes on the screen. There may be multiple layouts that can be changed at runtime, but we define only one. The macro vertically creates another (anonymous) pane that arranges one gadget below another.

Gadgets in CLIM operate directly on top of the event loop. When the pointer button is pressed, it is handled by activating the callback, that updates the frame's value and the label. Effects are visible immediately.

Now if we want the demo to look nicer, all we need to do is to fiddle a bit with spacing and bordering in the :layouts section:

(define-application-frame counter-v1 ()

((value :initform 0 :accessor value))

(:panes

(tfield :label :label (princ-to-string (value *application-frame*))

:background +white+)

(button :push-button :label "Count"

:activate-callback (lambda (gadget)

(declare (ignore gadget))

(with-application-frame (frame)

(incf (value frame))

(setf (label-pane-label (find-pane-named frame 'tfield))

(princ-to-string (value frame)))))))

(:layouts (default

(spacing (:thickness 10)

(horizontally ()

(100

(bordering (:thickness 1 :background +black+)

(spacing (:thickness 4 :background +white+) tfield)))

(15 (make-pane :label))

(100 button))))))

;;; Start the application (if not already running).

;; (find-application-frame 'counter-v1)

This gives us a layout that is roughly similar to the example presented on the 7GUIs page.

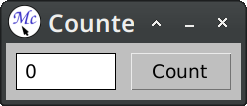

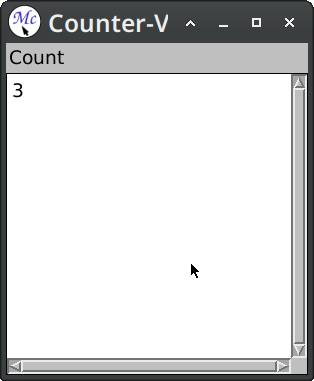

Version 2: Using the CLIM Command Loop

Unlike gadgets, stream panes in CLIM operate on top of the command loop. A single command may span multiple events after which we redisplay the stream to reflect the new state of the model. This is closer to the interaction type found in the command line interfaces:

(define-application-frame counter-v2 ()

((value :initform 0 :accessor value))

(:pane :application

:display-function (lambda (frame stream)

(format stream "~d" (value frame)))))

(define-counter-v2-command (com-incf-value :name "Count" :menu t)

()

(with-application-frame (frame)

(incf (value frame))))

;; (find-application-frame 'counter-v2)

Here we've used :pane option this is a syntactic sugar for when we have only one named pane. Skipping :layouts clause means that named panes will be stacked vertically one below another.

Defining the application frame defines a command-defining macro. When we define a command with define-counter-v2-command, then this command will be inserted into a command table associated with the frame. Passing the option :menu t causes the command to be available in the frame menu as a top-level entry.

After the command is executed (in this case it modifies the counter value), the application pane is redisplayed; that is a display function is called, and its output is captured. In more demanding scenarios it is possible to refine both the time of redisplay and the scope of changes.

Now we want the demo to look nicer and to have a button counterpart placed beside the counter value, to resemble the example more:

(define-presentation-type counter-button ())

(define-application-frame counter-v2 ()

((value :initform 0 :accessor value))

(:menu-bar nil)

(:pane :application

:width 250 :height 32

:borders nil :scroll-bars nil

:end-of-line-action :allow

:display-function (lambda (frame stream)

(formatting-item-list (stream :n-columns 2)

(formatting-cell (stream :min-width 100 :min-height 32)

(format stream "~d" (value frame)))

(formatting-cell (stream :min-width 100 :min-height 32)

(with-output-as-presentation (stream nil 'counter-button :single-box t)

(surrounding-output-with-border (stream :padding-x 20 :padding-y 0

:filled t :ink +light-grey+)

(format stream "Count"))))))))

(define-counter-v2-command (com-incf-value :name "Count" :menu t)

()

(with-application-frame (frame)

(incf (value frame))))

(define-presentation-to-command-translator act-incf-value

(counter-button com-incf-value counter-v2)

(object)

`())

;; (find-application-frame 'counter-v2)

The main addition is the definition of a new presentation type counter-button. This faux button is printed inside a cell and surrounded with a background. Later we define a translator that converts clicks on the counter button to the com-incf-value command. The translator body returns arguments for the command.

Presenting an object on the stream associates a semantic meaning with the output. We can now extend the application with new gestures (names :scroll-up and :scroll-down are McCLIM-specific):

(define-counter-v2-command (com-scroll-value :name "Increment")

((count 'integer))

(with-application-frame (frame)

(if (plusp count)

(incf (value frame) count)

(decf (value frame) (- count)))))

(define-presentation-to-command-translator act-scroll-up-value

(counter-button com-scroll-value counter-v2 :gesture :scroll-up)

(object)

`(10))

(define-presentation-to-command-translator act-scroll-dn-value

(counter-button com-scroll-value counter-v2 :gesture :scroll-down)

(object)

`(-10))

(define-presentation-action act-popup-value

(counter-button nil counter-v2 :gesture :describe)

(object frame)

(notify-user frame (format nil "Current value: ~a" (value frame))))

A difference between presentation to command translators and presentation actions is that the latter does not automatically progress the command loop. Actions are often used for side effects, help, inspection etc.

Conclusion

In this short post we've solved the first task from the 7GUIs challenge. We've used two techniques available in CLIM - using layouts and gadgets, and using display and command tables. Both techniques can be combined, but differences are visible at a glance:

- gadgets provide easy and reusable components for rudimentary interactions

- streams provide extensible and reusable abstractions for semantic interactions

This post only scratched the capabilities of the latter, but the second version demonstrates why the command loop and presentations scale better than gadget-only solutions.

Following tasks have gradually increasing level of difficulty that will help us to emphasize how useful are presentations and commands when we want to write maintainable applications with reusable user-defined graphical metaphors.

26 Jan 2026 12:00am GMT

23 Jan 2026

Django community aggregator: Community blog posts

Django community aggregator: Community blog posts

Django News - Djangonaut Space Session 6 Applications Open! - Jan 23rd 2026

News

uvx.sh by Astral

Astral, makers of uv, have a new "install Python tools with a single command" website.

Python Software Foundation

Announcing Python Software Foundation Fellow Members for Q4 2025!

The PSF announces new PSF Fellows for Q4 2025, recognizing community leaders who contribute projects, education, events, and mentorship worldwide.

Departing the Python Software Foundation (Staff)

Ee Durbin is stepping down as PSF Director of Infrastructure, transitioning PyPI and infrastructure responsibilities to staff while providing 20% support for six months.

Djangonaut Space News

Announcing Djangonaut Space Session 6 Applications Open!

Djangonaut Space Session 6 opens applications for an eight-week mentorship program to contribute to Django core, accessibility, third-party projects, and new BeeWare documentation.

New Admins and Advisors for Djangonaut Space

Djangonaut Space appoints Lilian Tran and Raffaella Suardini as admins and Priya Pahwa as advisor, strengthening Django community leadership and contributor support.

Wagtail CMS News

llms.txt - preparing Wagtail docs for AI tools

Wagtail publishes developer and user documentation in llms.txt to provide authoritative, AI-friendly source files for LLMs, improving accessibility and evaluation for smaller models.

Updates to Django

Today, "Updates to Django" is presented by Pradhvan from Djangonaut Space! 🚀

Last week we had 16 pull requests merged into Django by 11 different contributors - including 3 first-time contributors! Congratulations to Kundan Yadav, Parth Paradkar, and Rudraksha Dwivedi for having their first commits merged into Django - welcome on board! 🥳

This week's Django highlights: 🦄

ModelIterablenow checks if foreign key fields are deferred before attempting optimization, avoiding N+1 queries when using.only()on related managers. (#35442)- The XML deserializer now raises errors for invalid nested elements instead of silently processing them, preventing potential performance issues from malformed fixtures. (#36769)

- Error messages now clearly indicate when annotated fields are excluded by earlier

.values()calls in chained queries. (#36352) - Improved performance in

construct_change_message()by avoiding unnecessarytranslation_override()calculation when logging additions. (#36801)

Django Newsletter

Articles

Unconventional PostgreSQL Optimizations

Use PostgreSQL check constraints, function-based or virtual generated columns, and hash-based exclusion constraints to reduce scans, shrink indexes, and enforce uniqueness efficiently.

Django 6.0 Tasks: a framework without a worker

Django 6.0 adds a native tasks abstraction but only supports one-off tasks without scheduling, retries, persistence, or a worker backend, limiting real-world utility.

I Created a Game Engine for Django?

Multiplayer Snake implemented in Django using Django LiveView, 270 lines of Python, server side game state, WebSocket driven HTML updates, no custom JavaScript.

Django Icon packs with template partials

Reusable SVG icon pack using Django template partialdefs and dynamic includes to render configurable icons with classes, avoiding custom template tags.

Building Critical Infrastructure with htmx: Network Automation for the Paris 2024 Olympics

HTMX combined with Django, Celery, and procedural server-side views enabled rapid, maintainable network automation tools for Paris 2024, improving developer productivity and AI-assisted code generation.

Don't Let Old Migrations Haunt Your Codebase

Convert old data migrations that have already run into noop RunPython migrations to preserve the migration graph while preventing test slowdowns and legacy breakage.

Django Time-Based Lookups: A Performance Trap

Your "simple" __date filter might be turning a millisecond query into a 30-second table scan-here's the subtle Django ORM trap and the one-line fix that restores index-level performance.

Podcasts

Django Brew

DjangoCon US 2025 recap covering conference highlights, community discussions on a REST story, SQLite in production, background tasks, and frontend tools like HTMX.

Django Job Board

Two new senior roles just hit the Django Job Board, one focused on building Django apps at SKYCATCHFIRE and another centered on Python work with data heavy systems at Dun & Bradstreet.

Senior Django Developer at SKYCATCHFIRE 🆕

Senior Python Developer at Cial Dun & Bradstreet

Django Newsletter

Projects

quertenmont/django-msgspec-field

Django JSONField with msgspec structs as a Schema.

radiac/django-nanopages

Generate Django pages from Markdown, HTML, and Django template files.

This RSS feed is published on https://django-news.com/. You can also subscribe via email.

23 Jan 2026 5:00pm GMT

22 Jan 2026

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

James Bottomley: Adding Two Factor Authentication to Android (LineageOS)

I really like the idea of using biometrics to add extra security, but have always hated the idea that simply touching the fingerprint sensor would unlock your entire phone, so in my version of LineageOS the touch to unlock feature is disabled but I still use second factor biometrics for the security of various apps. Effectively the android unlock policy is Fingerprint OR PIN/Pattern/Password and I simply want that OR to become an AND.

The problem

The idea of using two factor authentication (2FA) was pioneered by GrapheneOS but since I like the smallness of the Pixel 3 that's not available to me (plus it only seems to work with pin and fingerprint and my preferred unlock is pattern). However, since I build my own LineageOS anyway (so I can sign and secure boot it) I thought I'd look into adding the feature … porting from GrapheneOS should be easy, right? In fact, when looking in the GrapheneOS code for frameworks/base, there are about nine commits adding the feature:

a7a19bf8fb98 add second factor to fingerprint unlock

5dd0e04f82cd add second factor UI

9cc17fd97296 add second factor to FingerprintService

c92a23473f3f add second factor to LockPattern classes

c504b05c933a add second factor to TrustManagerService

0aa7b9ec8408 add second factor to AdaptiveAuthService

62bbdf359687 add second factor to LockSettingsStateListener

7429cc13f971 add second factor to LockSettingsService

6e2d499a37a2 add second factor to DevicePolicyManagerServiceAnd a diffstat of over 3,000 lines … which seems a bit much for changing an OR to an AND. Of course, the reason it's so huge is because they didn't change the OR, they implemented an entirely new bouncer (bouncer being the android term in the code for authorisation gateway) that did pin and fingerprint in addition to the other three bouncers doing pattern, pin and password. So not only would I have to port 3,000 lines of code, but if I want a bouncer doing fingerprint and pattern, I'd have to write it. I mean colour me lazy but that seems way too much work for such an apparently simple change.

Creating a new 2FA unlock

So is it actually easy? The rest of this post documents my quest to find out. Android code itself isn't always easy to read: being Java it's object oriented, but the curse of object orientation is that immediately after you've written the code, you realise you got the object model wrong and it needs to be refactored … then you realise the same thing after the first refactor and so on until you either go insane or give up. Even worse when many people write the code they all end up with slightly different views of what the object model should be. The result is what you see in Android today: model inconsistency and redundancy which get in the way when you try to understand the code flow simply by reading it. One stroke of luck was that there is actually only a single method all of the unlock types other than fingerprint go through KeyguardSecurityContainerController.showNextSecurityScreenOrFinish() with fingerprint unlocking going via a listener to the KeyguardUpdateMonitorCallback.onBiometricAuthenticated(). And, thanks to already disabling fingerprint only unlock, I know that if I simply stop triggering the latter event, it's enough to disable fingerprint only unlock and all remaining authentication goes through the former callback. So to implement the required AND function, I just have to do this and check that a fingerprint authentication is also present in showNext.. (handily signalled by KeyguardUpdateMonitor.userUnlockedWithBiometric()). The latter being set fairly late in the sequence that does the onBiometricAuthenticated() callback (so I have to cut it off after this to prevent fingerprint only unlock). As part of the Android redundancy, there's already a check for fingerprint unlock as its own segment of a big if/else statement in the showNext.. code; it's probably a vestige from a different fingerprint unlock mechanism but I disabled it when the user enables 2FA just in case. There's also an insanely complex set of listeners for updating the messages on the lockscreen to guide the user through unlocking, which I decided not to change (if you enable 2FA, you need to know how to use it). Finally, I diverted the code that would call the onBiometricAuthenticated() and instead routed it to onBiometricDetected() which triggers the LockScreen bouncer to pop up, so now you wake your phone, touch the fingerprint to the back, when authenticated, it pops up the bouncer and you enter your pin/pattern/password … neat (and simple)!

Well, not so fast. While the code above works perfectly if the lockscreen is listening for fingerprints, there are two cases where it doesn't: if the phone is in lockdown or on first boot (because the Android way of not allowing fingerprint only authentication for those cases is not to listen for it). At this stage, my test phone is actually unusable because I can never supply the required fingerprint for 2FA unlocking. Fortunately a rooted adb can update the 2FA in the secure settings service: simply run sqlite3 on /data/system/locksettings.db and flip user_2fa from 1 to 0.

The fingerprint listener is started in KeyguardUpdateMonitor, but it has a fairly huge set of conditions in updateFingerprintListeningState() which is also overloaded by doing detection as well as authentication. In the end it's not as difficult as it looks: shouldListenForFingerprint needs to be true and runDetect needs to be false. However, even then it doesn't actually work (although debugging confirms it's trying to start the fingerprint listening service); after a lot more debugging it turns out that the biometric server process, which runs fingerprint detection and authentication, also has a redundant check for whether the phone is encrypted or in lockdown and refuses to start if it is, which also now needs to return false for 2FA and bingo, it works in all circumstances.

Conclusion

The final diffstat for all of this is

5 files changed, 55 insertions(+), 3 deletions(-)So I'd say that is way simpler than the GrapheneOS one. All that remains is to add a switch for the setting (under the fingerprint settings) in packages/apps/Settings and it's done. If you're brave enough to try this for yourself you can go to my github account and get both the frameworks and settings commits (if you don't want fingerprint unlock disable when 2FA isn't selected, you'll have to remove the head commit in frameworks). I suppose I should also add I've up-ported all of my other security stuff and am now on Android-15 (LineageOS-22.2).

22 Jan 2026 5:17pm GMT

Planet Plone - Where Developers And Integrators Write

Planet Plone - Where Developers And Integrators Write

Maurits van Rees: Mikel Larreategi: How we deploy cookieplone based projects.

We saw that cookieplone was coming up, and Docker, and as game changer uv making the installation of Python packages much faster.

With cookieplone you get a monorepo, with folders for backend, frontend, and devops. devops contains scripts to setup the server and deploy to it. Our sysadmins already had some other scripts. So we needed to integrate that.

First idea: let's fork it. Create our own copy of cookieplone. I explained this in my World Plone Day talk earlier this year. But cookieplone was changing a lot, so it was hard to keep our copy updated.

Maik Derstappen showed me copier, yet another templating language. Our idea: create a cookieplone project, and then use copier to modify it.

What about the deployment? We are on GitLab. We host our runners. We use the docker-in-docker service. We develop on a branch and create a merge request (pull request in GitHub terms). This activates a piple to check-test-and-build. When it is merged, bump the version, use release-it.

Then we create deploy keys and tokens. We give these access to private GitLab repositories. We need some changes to SSH key management in pipelines, according to our sysadmins.

For deployment on the server: we do not yet have automatic deployments. We did not want to go too fast. We are testing the current pipelines and process, see if they work properly. In the future we can think about automating deployment. We just ssh to the server, and perform some commands there with docker.

Future improvements:

- Start the docker containers and curl/wget the

/okendpoint. - lock files for the backend, with pip/uv.

22 Jan 2026 9:43am GMT

Maurits van Rees: Jakob Kahl and Erico Andrei: Flying from one Plone version to another

This is a talk about migrating from Plone 4 to 6 with the newest toolset.

There are several challenges when doing Plone migrations:

- Highly customized source instances: custom workflow, add-ons, not all of them with versions that worked on Plone 6.

- Complex data structures. For example a Folder with a Link as default page, with pointed to some other content which meanwhile had been moved.

- Migrating Classic UI to Volto

- Also, you might be migrating from a completely different CMS to Plone.

How do we do migrations in Plone in general?

- In place migrations. Run migration steps on the source instance itself. Use the standard upgrade steps from Plone. Suitable for smaller sites with not so much complexity. Especially suitable if you do only a small Plone version update.

- Export - import migrations. You extract data from the source, transform it, and load the structure in the new site. You transform the data outside of the source instance. Suitable for all kinds of migrations. Very safe approach: only once you are sure everything is fine, do you switch over to the newly migrated site. Can be more time consuming.

Let's look at export/import, which has three parts:

- Extraction: you had collective.jsonify, transmogrifier, and now collective.exportimport and plone.exportimport.

- Transformation: transmogrifier, collective.exportimport, and new: collective.transmute.

- Load: Transmogrifier, collective.exportimport, plone.exportimport.

Transmogrifier is old, we won't talk about it now. collective.exportimport: written by Philip Bauer mostly. There is an @@export_all view, and then @@import_all to import it.

collective.transmute is a new tool. This is made to transform data from collective.exportimport to the plone.exportimport format. Potentially it can be used for other migrations as well. Highly customizable and extensible. Tested by pytest. It is standalone software with a nice CLI. No dependency on Plone packages.

Another tool: collective.html2blocks. This is a lightweight Python replacement for the JavaScript Blocks conversion tool. This is extensible and tested.

Lastly plone.exportimport. This is a stripped down version of collective.exportimport. This focuses on extract and load. No transforms. So this is best suited for importing to a Plone site with the same version.

collective.transmute is in alpha, probably a 1.0.0 release in the next weeks. Still missing quite some documentation. Test coverage needs some improvements. You can contribute with PRs, issues, docs.

22 Jan 2026 9:43am GMT

Maurits van Rees: Fred van Dijk: Behind the screens: the state and direction of Plone community IT

This is a talk I did not want to give.

I am team lead of the Plone Admin team, and work at kitconcept.

The current state: see the keynotes, lots happening on the frontend. Good.

The current state of our IT: very troubling and daunting.

This is not a 'blame game'. But focussing on resources and people this conference should be a first priority. We are a real volunteer organisation, nobody is pushing anybody around. That is a strength, but also a weakness. We also see that in the Admin team.

The Admin team is 4 senior Plonistas as allround admin, 2 release managers, 2 CI/CD experts. 3 former board members, everyone overburdened with work. We had all kinds of plans for this year, but we have mostly been putting out fires.

We are a volunteer organisation, and don't have a big company behind us that can throw money at the problems. Strength and weakness. In all society it is a problem that volunteers are decreasing.

Root causes:

- We failed to scale down in time in our IT landscape and usage.

- We have no clean role descriptions, team descriptions, we can't ask a minimum effort per week or month.

- The trend is more communication channels, platforms to join and promote yourself, apps to use.

Overview of what have have to keep running as admin team:

- Support main development process: github, CI/CD, Jenkins main and runners, dist.plone.org.

- Main communication, documentation: pone.org, docs.plone.org, training.plone.org, conf and country sites, Matomo.

- Community office automation: Google docds, workspacae, Quaive, Signal, Slack

- Broader: Discourse and Discord

The first two are really needed, the second we already have some problems with.

Some services are self hosted, but also a lot of SAAS services/platforms. In all, it is quite a bit.

The Admin team does not officially support all of these, but it does provide fallback support. It is too much for the current team.

There are plans for what we can improve in the short term. Thank you to a lot of people that I have already talked to about this. 3 areas: GitHub setup and config, Google Workspace, user management.

On GitHub we have a sponsored OSS plan. So we have extra features for free, but it not enough by far. User management: hard to get people out. You can't contact your members directly. E-mail has been removed, for privacy. Features get added on GitHub, and no complete changelog.

Challenge on GitHub: we have public repositories, but we also have our deployments in there. Only really secure would be private repositories, otherwise the danger is that credentials or secret could get stolen. Every developer with access becomes an attack vector. Auditing is available for only 6 months. A simple question like: who has been active for the last 2 years? No, can't do.

Some actionable items on GitHub:

- We will separate the contributor agreement check from the organisation membership. We create a hidden team for those who signed, and use that in the check.

- Cleanup users, use Contributors team, Developers

- Active members: check who has contributed the last years.

- There have been security incidents. Someone accidentally removed a few repositories. Someone's account got hacked, luckily discovered within a few hours, and some actions had already been taken.

- More fine grained teams to control repository access.

- Use of GitHub Discussions for some central communication of changes.

- Use project management better.

- The elephant in the room that we have practice on this year, and ongoing: the Collective organisation. This was free for all, very nice, but the development world is not a nice and safe place anymore. So we already needed to lock down some things there.

- Keep deployments and the secrets all out of GitHub, so no secrets can be stolen.

Google Workspace:

- We are dependent on this.

- No user management. Admins have had access because they were on the board, but they kept access after leaving the board. So remove most inactive users.

- Spam and moderation issues

- We could move to Google docs for all kinds of things. Use Google workspace drives for all things. But the Drive UI is a mess, so docs can be in your personal account without you realizing it.

User management:

- We need separate standalone user management, but implementation is not clear.

- We cannot contact our members one on one.

Oh yes, Plone websites:

- upgrade plone.org

- self preservation: I know what needs to be done, and can do it, but have no time, focusing on the previous points instead.

22 Jan 2026 9:43am GMT

Django community aggregator: Community blog posts

Django community aggregator: Community blog posts

Python Leiden meetup: PostgreSQL + Python in 2026 -- Aleksandr Dinu

(One of my summaries of the Python Leiden meetup in Leiden, NL).

He's going to revisit common gotchas of Python ORM usage. Plus some Postgresql-specific tricks.

ORM (object relational mappers) define tables, columns etc using Python concepts: classes, attributes and methods. In your software, you work with objects instead of rows. They can help with database schema management (migrations and so). It looks like this:

class Question(models.Model):

question = models.Charfield(...)

answer = models.Charfield(...)

You often have Python "context managers" for database sessions.

ORMs are handy, but you must be beware of what you're fetching:

# Bad, grabs all objects and then takes the length using python: questions_count = len(Question.objects.all()) # Good: let the database do it, # the code does the equivalent of "SELECT COUNT(*)": questions_count = Question.objects.all().count()

Relational databases allow 1:M and N:M relations. You use them with JOIN in SQL. If you use an ORM, make sure you use the database to follow the relations. If you first grab the first set of objects and then grab the second kind of objects with python, your code will be much slower.

"Migrations" generated by your ORM to move from one version of your schema to the next are real handy. But not all SQL concepts can be expressed in an ORM. Custom types, stored procedures. You have to handle them yourselves. You can get undesired behaviour as specific database versions can take a long time rebuilding after a change.

Migrations are nice, but they can lead to other problems from a database maintainer's point of view, like the performance suddenly dropping. And optimising is hard as often you don't know which server is connecting how much and also you don't know what is queried. Some solutions for postgresql:

- log_line_prefix = '%a %u %d" to show who is connecting to which database.

- log_min_duration_statement = 1000 logs every query taking more than 1000ms.

- log_lock_waits = on for feedback on blocking operations (like migrations).

- Handy: feedback on the number of queries being done, as simple programming errors can translate into lots of small queries instead of one faster bigger one.

If you've found a slow query, run that query with EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS) the-query. BUFFERS tells you how many pages of 8k the server uses for your query (and whether those were memory or disk pages). This is so useful that they made it the default in postgresql 18.

Some tools:

- RegreSQL: performance regression testing. You feed it a list of queries that you worry about. It will store how those queries are executed and compare it with the new version of your code and warn you when one of those queries suddenly takes a lot more time.

- Squawk: tells you (in CI, like github actions) which migrations are backward-incompatible or that might take a long time.

- You can look at one of the branching tools: aimed at getting access to production databases for testing. Like running your migration against a "branch"/copy of production. There are several tricks that are used, like filesystem layers. "pg_branch" and "pgcow" are examples. Several DB-as-a-service products also provide it (Databricks Lakebase, Neon, Heroku, Postgres.ai).

22 Jan 2026 5:00am GMT

Python Leiden meetup: PR vs ROC curves, which to use - Sultan K. Imangaliyev

(One of my summaries of the Python Leiden meetup in Leiden, NL).

Precision-recall (PR) versus Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curves: which one to use if data is imbalanced?

Imbalanced data: for instance when you're investigating rare diseases. "Rare" means few people have them. So if you have data, most of the data will be of healthy people, there's a huge imbalance in the data.

Sensitivity versus specificity: sensitive means you find most of the sick people, specificity means you want as few false negatives and false positives as possible. Sensitivity/specificity looks a bit like precision/recall.

- Sensitivity: true positive rate.

- Specificity: false positive rate

If you classify, you can classify immediately into healthy/sick, but you can also use a probabilistic classifier which returns a chance (percentage) that someone can be classified as sick. You can then tweak which threshold you want to use: how sensitive and/or specific do you want to be?

PR and ROC curves (curve = graph showing the sensitivity/specificity relation on two axis) are two ways of measuring/visualising the sensitivity/specificity relation. He showed some data: if the data is imbalanced, PR is much better at evaluating your model. He compared balanced and imbalanced data with ROC and there was hardly a change in the curve.

He used scikit-learn for his data evaluations and demos.

22 Jan 2026 5:00am GMT

21 Jan 2026

DZone Java Zone

DZone Java Zone

The Future of Data Streaming with Apache Flink for Agentic AI

Agentic AI is changing how enterprises think about automation and intelligence. Agents are no longer reactive systems. They are goal-driven, context-aware, and capable of autonomous decision-making. But to operate effectively, agents must be connected to the real-time pulse of the business. This is where data streaming with Apache Kafka and Apache Flink becomes essential.

Apache Flink is entering a new phase with the proposal of Flink Agents, a sub-project designed to power system-triggered, event-driven AI agents natively within Flink's streaming runtime. Let's explore what this means for the future of agentic systems in the enterprise.

21 Jan 2026 8:00pm GMT

Why High-Availability Java Systems Fail Quietly Before They Fail Loudly

Most engineers imagine failures as sudden events. A service crashes. A node goes down. An alert fires, and everyone jumps into action. In real high-availability Java systems, failures rarely behave that way. They almost always arrive quietly first.

Systems that have been running reliably for months or years begin to show small changes. Latency creeps up. Garbage collection pauses last a little longer. Thread pools spend more time near saturation. Nothing looks broken, and dashboards stay mostly green. Then one day, the system tips over, and the failure suddenly looks dramatic.

21 Jan 2026 2:00pm GMT

20 Jan 2026

Planet Lisp

Planet Lisp

Joe Marshall: Filter

One of the core ideas in functional programming is to filter a set of items by some criterion. It may be somewhat suprising to learn that lisp does not have a built-in function named "filter" "select", or "keep" that performs this operation. Instead, Common Lisp provides the "remove", "remove-if", and "remove-if-not" functions, which perform the complementary operation of removing items that satisfy or do not satisfy a given predicate.

The remove function, like similar sequence functions, takes an optional keyword :test-not argument that can be used to specify a test that must fail for an item to be considered for removal. Thus if you invert your logic for inclusion, you can use the remove function as a "filter" by specifying the predicate with :test-not.

> (defvar *nums* (map 'list (λ (n) (format nil "~r" n)) (iota 10)))

*NUMS*

;; Keep *nums* with four letters

> (remove 4 *nums* :key #'length :test-not #'=)

("zero" "four" "five" "nine")

;; Keep *nums* starting with the letter "t"

> (remove #\t *nums* :key (partial-apply-right #'elt 0) :test-not #'eql)

("two" "three")20 Jan 2026 11:46am GMT

16 Jan 2026

Planet Lisp

Planet Lisp

Scott L. Burson: FSet v2.2.0: JSON parsing/printing using Jzon

FSet v2.2.0, which is the version included in the recent Quicklisp release, has a new Quicklisp-loadable system, FSet/Jzon. It extends the Jzon JSON parser/printer to construct FSet collections when reading, and to be able to print them.

On parsing, JSON arrays produce FSet seqs; JSON objects produce FSet replay maps by default, but the parser can also be configured to produce ordinary maps or FSet tuples. For printing, any of these can be handled, as well as the standard Jzon types. The tuple representation provides a way to control the printing of `nil`, depending on the type of the corresponding key.

For details, see the GitLab MR.

NOTE: unfortunately, the v2.1.0 release had some bugs in the new seq code, and I didn't notice them until after v2.2.0 was in Quicklisp. If you're using seqs, I strongly recommend you pick up v2.2.2 or newer from GitLab or GitHub.

16 Jan 2026 8:05am GMT

14 Jan 2026

DZone Java Zone

DZone Java Zone

How to Secure a Spring AI MCP Server with an API Key via Spring Security

Instead of building custom integrations for a variety of AI assistants or Large language models (LLMs) you interact with - e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, or any custom LLM - you can now, thanks to the Model Context Protocol (MCP), develop a server once and use it everywhere.

This is exactly as we used to say about Java applications; that thanks to the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), they're WORA (Write Once Run Anywhere). They're built on one system and expected to run on any other Java-enabled system without further adjustments.

14 Jan 2026 1:00pm GMT

05 Jan 2026

Planet Twisted

Planet Twisted

Glyph Lefkowitz: How To Argue With Me About AI, If You Must

As you already know if you've read any of this blog in the last few years, I am a somewhat reluctant - but nevertheless quite staunch - critic of LLMs. This means that I have enthusiasts of varying degrees sometimes taking issue with my stance.

It seems that I am not going to get away from discussions, and, let's be honest, pretty intense arguments about "AI" any time soon. These arguments are starting to make me quite upset. So it might be time to set some rules of engagement.

I've written about all of these before at greater length, but this is a short post because it's not about the technology or making a broader point, it's about me. These are rules for engaging with me, personally, on this topic. Others are welcome to adopt these rules if they so wish but I am not encouraging anyone to do so.

Thus, I've made this post as short as I can so everyone interested in engaging can read the whole thing. If you can't make it through to the end, then please just follow Rule Zero.

Rule Zero: Maybe Don't

You are welcome to ignore me. You can think my take is stupid and I can think yours is. We don't have to get into an Internet Fight about it; we can even remain friends. You do not need to instigate an argument with me at all, if you think that my analysis is so bad that it doesn't require rebutting.

Rule One: No 'Just'

As I explained in a post with perhaps the least-predictive title I've ever written, "I Think I'm Done Thinking About genAI For Now", I've already heard a bunch of bad arguments. Don't tell me to 'just' use a better model, use an agentic tool, use a more recent version, or use some prompting trick that you personally believe works better. If you skim my work and think that I must not have deeply researched anything or read about it because you don't like my conclusion, that is wrong.

Rule Two: No 'Look At This Cool Thing'

Purely as a productivity tool, I have had a terrible experience with genAI. Perhaps you have had a great one. Neat. That's great for you. As I explained at great length in "The Futzing Fraction", my concern with generative AI is that I believe it is probably a net negative impact on productivity, based on both my experience and plenty of citations. Go check out the copious footnotes if you're interested in more detail.

Therefore, I have already acknowledged that you can get an LLM to do various impressive, cool things, sometimes. If I tell you that you will, on average, lose money betting on a slot machine, a picture of a slot machine hitting a jackpot is not evidence against my position.

Rule Two And A Half: Engage In Metacognition

I specifically didn't title the previous rule "no anecdotes" because data beyond anecdotes may be extremely expensive to produce. I don't want to say you can never talk to me unless you're doing a randomized controlled trial. However, if you are going to tell me an anecdote about the way that you're using an LLM, I am interested in hearing how you are compensating for the well-documented biases that LLM use tends to induce. Try to measure what you can.

Rule Three: Do Not Cite The Deep Magic To Me

As I explained in "A Grand Unified Theory of the AI Hype Cycle", I already know quite a bit of history of the "AI" label. If you are tempted to tell me something about how "AI" is really such a broad field, and it doesn't just mean LLMs, especially if you are trying to launder the reputation of LLMs under the banner of jumbling them together with other things that have been called "AI", I assure you that this will not be convincing to me.

Rule Four: Ethics Are Not Optional

I have made several arguments in my previous writing: there are ethical arguments, efficacy arguments, structuralist arguments, efficiency arguments and aesthetic arguments.

I am happy to, for the purposes of a good-faith discussion, focus on a specific set of concerns or an individual point that you want to make where you think I got something wrong. If you convince me that I am entirely incorrect about the effectiveness or predictability of LLMs in general or as specific LLM product, you don't need to make a comprehensive argument about whether one should use the technology overall. I will even assume that you have your own ethical arguments.

However, if you scoff at the idea that one should have any ethical boundaries at all, and think that there's no reason to care about the overall utilitarian impact of this technology, that it's worth using no matter what else it does as long as it makes you 5% better at your job, that's sociopath behavior.

This includes extreme whataboutism regarding things like the water use of datacenters, other elements of the surveillance technology stack, and so on.

Consequences

These are rules, once again, just for engaging with me. I have no particular power to enact broader sanctions upon you, nor would I be inclined to do so if I could. However, if you can't stay within these basic parameters and you insist upon continuing to direct messages to me about this topic, I will summarily block you with no warning, on mastodon, email, GitHub, IRC, or wherever else you're choosing to do that. This is for your benefit as well: such a discussion will not be a productive use of either of our time.

05 Jan 2026 5:22am GMT

04 Jan 2026

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Pete Zaitcev: The fall of LJ

Great, I am unable to comment at BG.

Theoretically, I have a spare place at Meenuvia, but that platform is also in decline. The owner, Pixy, has no time even to fix the slug problem that cropped up a few months ago (how do you regress a platform that was stable for 20 years, I don't know).

Most likely, I'll give up on blogging entirely, and move to Twitter or Fediverse.

04 Jan 2026 8:32pm GMT

Matthew Garrett: What is a PC compatible?

Wikipedia says "An IBM PC compatible is any personal computer that is hardware- and software-compatible with the IBM Personal Computer (IBM PC) and its subsequent models". But what does this actually mean? The obvious literal interpretation is for a device to be PC compatible, all software originally written for the IBM 5150 must run on it. Is this a reasonable definition? Is it one that any modern hardware can meet?

Before we dig into that, let's go back to the early days of the x86 industry. IBM had launched the PC built almost entirely around off-the-shelf Intel components, and shipped full schematics in the IBM PC Technical Reference Manual. Anyone could buy the same parts from Intel and build a compatible board. They'd still need an operating system, but Microsoft was happy to sell MS-DOS to anyone who'd turn up with money. The only thing stopping people from cloning the entire board was the BIOS, the component that sat between the raw hardware and much of the software running on it. The concept of a BIOS originated in CP/M, an operating system originally written in the 70s for systems based on the Intel 8080. At that point in time there was no meaningful standardisation - systems might use the same CPU but otherwise have entirely different hardware, and any software that made assumptions about the underlying hardware wouldn't run elsewhere. CP/M's BIOS was effectively an abstraction layer, a set of code that could be modified to suit the specific underlying hardware without needing to modify the rest of the OS. As long as applications only called BIOS functions, they didn't need to care about the underlying hardware and would run on all systems that had a working CP/M port.

By 1979, boards based on the 8086, Intel's successor to the 8080, were hitting the market. The 8086 wasn't machine code compatible with the 8080, but 8080 assembly code could be assembled to 8086 instructions to simplify porting old code. Despite this, the 8086 version of CP/M was taking some time to appear, and a company called Seattle Computer Products started producing a new OS closely modelled on CP/M and using the same BIOS abstraction layer concept. When IBM started looking for an OS for their upcoming 8088 (an 8086 with an 8-bit data bus rather than a 16-bit one) based PC, a complicated chain of events resulted in Microsoft paying a one-off fee to Seattle Computer Products, porting their OS to IBM's hardware, and the rest is history.

But one key part of this was that despite what was now MS-DOS existing only to support IBM's hardware, the BIOS abstraction remained, and the BIOS was owned by the hardware vendor - in this case, IBM. One key difference, though, was that while CP/M systems typically included the BIOS on boot media, IBM integrated it into ROM. This meant that MS-DOS floppies didn't include all the code needed to run on a PC - you needed IBM's BIOS. To begin with this wasn't obviously a problem in the US market since, in a way that seems extremely odd from where we are now in history, it wasn't clear that machine code was actually copyrightable. In 1982 Williams v. Artic determined that it could be even if fixed in ROM - this ended up having broader industry impact in Apple v. Franklin and it became clear that clone machines making use of the original vendor's ROM code wasn't going to fly. Anyone wanting to make hardware compatible with the PC was going to have to find another way.

And here's where things diverge somewhat. Compaq famously performed clean-room reverse engineering of the IBM BIOS to produce a functionally equivalent implementation without violating copyright. Other vendors, well, were less fastidious - they came up with BIOS implementations that either implemented a subset of IBM's functionality, or didn't implement all the same behavioural quirks, and compatibility was restricted. In this era several vendors shipped customised versions of MS-DOS that supported different hardware (which you'd think wouldn't be necessary given that's what the BIOS was for, but still), and the set of PC software that would run on their hardware varied wildly. This was the era where vendors even shipped systems based on the Intel 80186, an improved 8086 that was both faster than the 8086 at the same clock speed and was also available at higher clock speeds. Clone vendors saw an opportunity to ship hardware that outperformed the PC, and some of them went for it.

You'd think that IBM would have immediately jumped on this as well, but no - the 80186 integrated many components that were separate chips on 8086 (and 8088) based platforms, but crucially didn't maintain compatibility. As long as everything went via the BIOS this shouldn't have mattered, but there were many cases where going via the BIOS introduced performance overhead or simply didn't offer the functionality that people wanted, and since this was the era of single-user operating systems with no memory protection, there was nothing stopping developers from just hitting the hardware directly to get what they wanted. Changing the underlying hardware would break them.

And that's what happened. IBM was the biggest player, so people targeted IBM's platform. When BIOS interfaces weren't sufficient they hit the hardware directly - and even if they weren't doing that, they'd end up depending on behavioural quirks of IBM's BIOS implementation. The market for DOS-compatible but not PC-compatible mostly vanished, although there were notable exceptions - in Japan the PC-98 platform achieved significant success, largely as a result of the Japanese market being pretty distinct from the rest of the world at that point in time, but also because it actually handled Japanese at a point where the PC platform was basically restricted to ASCII or minor variants thereof.

So, things remained fairly stable for some time. Underlying hardware changed - the 80286 introduced the ability to access more than a megabyte of address space and would promptly have broken a bunch of things except IBM came up with an utterly terrifying hack that bit me back in 2009, and which ended up sufficiently codified into Intel design that it was one mechanism for breaking the original XBox security. The first 286 PC even introduced a new keyboard controller that supported better keyboards but which remained backwards compatible with the original PC to avoid breaking software. Even when IBM launched the PS/2, the first significant rearchitecture of the PC platform with a brand new expansion bus and associated patents to prevent people cloning it without paying off IBM, they made sure that all the hardware was backwards compatible. For decades, PC compatibility meant not only supporting the officially supported interfaces, it meant supporting the underlying hardware. This is what made it possible to ship install media that was expected to work on any PC, even if you'd need some additional media for hardware-specific drivers. It's something that still distinguishes the PC market from the ARM desktop market. But it's not as true as it used to be, and it's interesting to think about whether it ever was as true as people thought.

Let's take an extreme case. If I buy a modern laptop, can I run 1981-era DOS on it? The answer is clearly no. First, modern systems largely don't implement the legacy BIOS. The entire abstraction layer that DOS relies on isn't there, having been replaced with UEFI. When UEFI first appeared it generally shipped with a Compatibility Services Module, a layer that would translate BIOS interrupts into UEFI calls, allowing vendors to ship hardware with more modern firmware and drivers without having to duplicate them to support older operating systems1. Is this system PC compatible? By the strictest of definitions, no.

Ok. But the hardware is broadly the same, right? There's projects like CSMWrap that allow a CSM to be implemented on top of stock UEFI, so everything that hits BIOS should work just fine. And well yes, assuming they implement the BIOS interfaces fully, anything using the BIOS interfaces will be happy. But what about stuff that doesn't? Old software is going to expect that my Sound Blaster is going to be on a limited set of IRQs and is going to assume that it's going to be able to install its own interrupt handler and ACK those on the interrupt controller itself and that's really not going to work when you have a PCI card that's been mapped onto some APIC vector, and also if your keyboard is attached via USB or SPI then reading it via the CSM will work (because it's calling into UEFI to get the actual data) but trying to read the keyboard controller directly won't2, so you're still actually relying on the firmware to do the right thing but it's not, because the average person who wants to run DOS on a modern computer owns three fursuits and some knee length socks and while you are important and vital and I love you all you're not enough to actually convince a transglobal megacorp to flip the bit in the chipset that makes all this old stuff work.

But imagine you are, or imagine you're the sort of person who (like me) thinks writing their own firmware for their weird Chinese Thinkpad knockoff motherboard is a good and sensible use of their time - can you make this work fully? Haha no of course not. Yes, you can probably make sure that the PCI Sound Blaster that's plugged into a Thunderbolt dock has interrupt routing to something that is absolutely no longer an 8259 but is pretending to be so you can just handle IRQ 5 yourself, and you can probably still even write some SMM code that will make your keyboard work, but what about the corner cases? What if you're trying to run something built with IBM Pascal 1.0? There's a risk that it'll assume that trying to access an address just over 1MB will give it the data stored just above 0, and now it'll break. It'd work fine on an actual PC, and it won't work here, so are we PC compatible?

That's a very interesting abstract question and I'm going to entirely ignore it. Let's talk about PC graphics3. The original PC shipped with two different optional graphics cards - the Monochrome Display Adapter and the Color Graphics Adapter. If you wanted to run games you were doing it on CGA, because MDA had no mechanism to address individual pixels so you could only render full characters. So, even on the original PC, there was software that would run on some hardware but not on other hardware.

Things got worse from there. CGA was, to put it mildly, shit. Even IBM knew this - in 1984 they launched the PCjr, intended to make the PC platform more attractive to home users. As well as maybe the worst keyboard ever to be associated with the IBM brand, IBM added some new video modes that allowed displaying more than 4 colours on screen at once4, and software that depended on that wouldn't display correctly on an original PC. Of course, because the PCjr was a complete commercial failure, it wouldn't display correctly on any future PCs either. This is going to become a theme.

There's never been a properly specified PC graphics platform. BIOS support for advanced graphics modes5 ended up specified by VESA rather than IBM, and even then getting good performance involved hitting hardware directly. It wasn't until Microsoft specced DirectX that anything was broadly usable even if you limited yourself to Microsoft platforms, and this was an OS-level API rather than a hardware one. If you stick to BIOS interfaces then CGA-era code will work fine on graphics hardware produced up until the 20-teens, but if you were trying to hit CGA hardware registers directly then you're going to have a bad time. This isn't even a new thing - even if we restrict ourselves to the authentic IBM PC range (and ignore the PCjr), by the time we get to the Enhanced Graphics Adapter we're not entirely CGA compatible. Is an IBM PC/AT with EGA PC compatible? You'd likely say "yes", but there's software written for the original PC that won't work there.

And, well, let's go even more basic. The original PC had a well defined CPU frequency and a well defined CPU that would take a well defined number of cycles to execute any given instruction. People could write software that depended on that. When CPUs got faster, some software broke. This resulted in systems with a Turbo Button - a button that would drop the clock rate to something approximating the original PC so stuff would stop breaking. It's fine, we'd later end up with Windows crashing on fast machines because hardware details will absolutely bleed through.

So, what's a PC compatible? No modern PC will run the DOS that the original PC ran. If you try hard enough you can get it into a state where it'll run most old software, as long as it doesn't have assumptions about memory segmentation or your CPU or want to talk to your GPU directly. And even then it'll potentially be unusable or crash because time is hard.

The truth is that there's no way we can technically describe a PC Compatible now - or, honestly, ever. If you sent a modern PC back to 1981 the media would be amazed and also point out that it didn't run Flight Simulator. "PC Compatible" is a socially defined construct, just like "Woman". We can get hung up on the details or we can just chill.

-

Windows 7 is entirely happy to boot on UEFI systems except that it relies on being able to use a BIOS call to set the video mode during boot, which has resulted in things like UEFISeven to make that work on modern systems that don't provide BIOS compatibility ↩︎

-

Back in the 90s and early 2000s operating systems didn't necessarily have native drivers for USB input devices, so there was hardware support for trapping OS accesses to the keyboard controller and redirecting that into System Management Mode where some software that was invisible to the OS would speak to the USB controller and then fake a response anyway that's how I made a laptop that could boot unmodified MacOS X ↩︎

-

(my name will not be Wolfwings Shadowflight) ↩︎

-

Yes yes ok 8088 MPH demonstrates that if you really want to you can do better than that on CGA ↩︎

-

and by advanced we're still talking about the 90s, don't get excited ↩︎

04 Jan 2026 3:11am GMT

02 Jan 2026

Planet Twisted

Planet Twisted

Glyph Lefkowitz: The Next Thing Will Not Be Big

The dawning of a new year is an opportune moment to contemplate what has transpired in the old year, and consider what is likely to happen in the new one.

Today, I'd like to contemplate that contemplation itself.

The 20th century was an era characterized by rapidly accelerating change in technology and industry, creating shorter and shorter cultural cycles of changes in lifestyles. Thus far, the 21st century seems to be following that trend, at least in its recently concluded first quarter.

The early half of the twentieth century saw the massive disruption caused by electrification, radio, motion pictures, and then television.

In 1971, Intel poured gasoline on that fire by releasing the 4004, a microchip generally recognized as the first general-purpose microprocessor. Popular innovations rapidly followed: the computerized cash register, the personal computer, credit cards, cellular phones, text messaging, the Internet, the web, online games, mass surveillance, app stores, social media.

These innovations have arrived faster than previous generations, but also, they have crossed a crucial threshold: that of the human lifespan.

While the entire second millennium A.D. has been characterized by a gradually accelerating rate of technological and social change - the printing press and the industrial revolution were no slouches, in terms of changing society, and those predate the 20th century - most of those changes had the benefit of unfolding throughout the course of a generation or so.

Which means that any individual person in any given century up to the 20th might remember one major world-altering social shift within their lifetime, not five to ten of them. The diversity of human experience is vast, but most people would not expect that the defining technology of their lifetime was merely the latest in a progression of predictable civilization-shattering marvels.

Along with each of these successive generations of technology, we minted a new generation of industry titans. Westinghouse, Carnegie, Sarnoff, Edison, Ford, Hughes, Gates, Jobs, Zuckerberg, Musk. Not just individual rich people, but entire new classes of rich people that did not exist before. "Radio DJ", "Movie Star", "Rock Star", "Dot Com Founder", were all new paths to wealth opened (and closed) by specific technologies. While most of these people did come from at least some level of generational wealth, they no longer came from a literal hereditary aristocracy.

To describe this new feeling of constant acceleration, a new phrase was coined: "The Next Big Thing". In addition to denoting that some Thing was coming and that it would be Big (i.e.: that it would change a lot about our lives), this phrase also carries the strong implication that such a Thing would be a product. Not a development in social relationships or a shift in cultural values, but some new and amazing form of conveying salted meat paste or what-have-you, that would make whatever lucky tinkerer who stumbled into it into a billionaire - along with any friends and family lucky enough to believe in their vision and get in on the ground floor with an investment.

In the latter part of the 20th century, our entire model of capital allocation shifted to account for this widespread belief. No longer were mega-businesses built by bank loans, stock issuances, and reinvestment of profit, the new model was "Venture Capital". Venture capital is a model of capital allocation explicitly predicated on the idea that carefully considering each bet on a likely-to-succeed business and reducing one's risk was a waste of time, because the return on the equity from the Next Big Thing would be so disproportionately huge - 10x, 100x, 1000x - that one could afford to make at least 10 bad bets for each good one, and still come out ahead.

The biggest risk was in missing the deal, not in giving a bunch of money to a scam. Thus, value investing and focus on fundamentals have been broadly disregarded in favor of the pursuit of the Next Big Thing.

If Americans of the twentieth century were temporarily embarrassed millionaires, those of the twenty-first are all temporarily embarrassed FAANG CEOs.

The predicament that this tendency leaves us in today is that the world is increasingly run by generations - GenX and Millennials - with the shared experience that the computer industry, either hardware or software, would produce some radical innovation every few years. We assume that to be true.

But all things change, even change itself, and that industry is beginning to slow down. Physically, transistor density is starting to brush up against physical limits. Economically, most people are drowning in more compute power than they know what to do with anyway. Users already have most of what they need from the Internet.

The big new feature in every operating system is a bunch of useless junk nobody really wants and is seeing remarkably little uptake. Social media and smartphones changed the world, true, but… those are both innovations from 2008. They're just not new any more.

So we are all - collectively, culturally - looking for the Next Big Thing, and we keep not finding it.

It wasn't 3D printing. It wasn't crowdfunding. It wasn't smart watches. It wasn't VR. It wasn't the Metaverse, it wasn't Bitcoin, it wasn't NFTs1.