13 Mar 2026

Planet Python

Planet Python

Talk Python to Me: #540: Modern Python monorepo with uv and prek

Monorepos -- you've heard the talks, you've read the blog posts, maybe you've seen a few tantalizing glimpses into how Google or Meta organize their massive codebases. But it's often in the abstract and behind closed doors. What if you could crack open a real, production monorepo, one with over a million lines of Python and over 100 of sub-packages, and actually see how it's built, step by step, using modern tools and standards? That's exactly what Apache Airflow gives us. <br/> <br/> On this episode, I sit down with Jarek Potiuk and Amogh Desai, two of Airflow's top contributors, to go inside one of the largest open-source Python monorepos in the world and learn how they manage it with uv, pyproject.toml, and the latest packaging standards, so you can apply those same patterns to your own projects.<br/> <br/> <strong>Episode sponsors</strong><br/> <br/> <a href='https://talkpython.fm/agentic-ai'>Agentic AI Course</a><br> <a href='https://talkpython.fm/devopsbook'>Python in Production</a><br> <a href='https://talkpython.fm/training'>Talk Python Courses</a><br/> <br/> <h2 class="links-heading mb-4">Links from the show</h2> <div><strong>Guests</strong><br/> <strong>Amogh Desai</strong>: <a href="https://github.com/amoghrajesh?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >github.com</a><br/> <strong>Jarek's GitHub</strong>: <a href="https://github.com/potiuk?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >github.com</a><br/> <br/> <strong>definition of a monorepo</strong>: <a href="https://monorepo.tools?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >monorepo.tools</a><br/> <strong>airflow</strong>: <a href="https://airflow.apache.org?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >airflow.apache.org</a><br/> <strong>Activity</strong>: <a href="https://github.com/apache/airflow/pulse?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >github.com</a><br/> <strong>OpenAI</strong>: <a href="https://airflowsummit.org/sessions/2025/airflow-openai/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >airflowsummit.org</a><br/> <strong>Part 1. Pains of big modular Python projects</strong>: <a href="https://medium.com/apache-airflow/modern-python-monorepo-for-apache-airflow-part-1-1fe84863e1e1?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >medium.com</a><br/> <strong>Part 2. Modern Python packaging standards and tools for monorepos</strong>: <a href="https://medium.com/apache-airflow/modern-python-monorepo-for-apache-airflow-part-2-9b53e21bcefc?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >medium.com</a><br/> <strong>Part 3. Monorepo on steroids - modular prek hooks</strong>: <a href="https://medium.com/apache-airflow/modern-python-monorepo-for-apache-airflow-part-3-77373d7c45a6?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >medium.com</a><br/> <strong>Part 4. Shared "static" libraries in Airflow monorepo</strong>: <a href="https://medium.com/apache-airflow/modern-python-monorepo-for-apache-airflow-part-4-c9d9393a696a?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >medium.com</a><br/> <strong>PEP-440</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0440/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-517</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0517/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-518</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0518/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-566</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0566/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-561</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0561/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-660</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0660/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-621</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0621/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-685</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0685/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-723</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0732/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-735</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0735/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>uv</strong>: <a href="https://docs.astral.sh/uv/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >docs.astral.sh</a><br/> <strong>uv workspaces</strong>: <a href="https://blobs.talkpython.fm/airflow-workspaces.png?cache_id=294f57" target="_blank" >blobs.talkpython.fm</a><br/> <strong>prek.j178.dev</strong>: <a href="https://prek.j178.dev?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >prek.j178.dev</a><br/> <strong>your presentation at FOSDEM26</strong>: <a href="https://fosdem.org/2026/schedule/event/WE7NHM-modern-python-monorepo-apache-airflow/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >fosdem.org</a><br/> <strong>Tallyman</strong>: <a href="https://github.com/mikeckennedy/tallyman?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >github.com</a><br/> <br/> <strong>Watch this episode on YouTube</strong>: <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SKd78ImNgEo" target="_blank" >youtube.com</a><br/> <strong>Episode #540 deep-dive</strong>: <a href="https://talkpython.fm/episodes/show/540/modern-python-monorepo-with-uv-and-prek#takeaways-anchor" target="_blank" >talkpython.fm/540</a><br/> <strong>Episode transcripts</strong>: <a href="https://talkpython.fm/episodes/transcript/540/modern-python-monorepo-with-uv-and-prek" target="_blank" >talkpython.fm</a><br/> <br/> <strong>Theme Song: Developer Rap</strong><br/> <strong>🥁 Served in a Flask 🎸</strong>: <a href="https://talkpython.fm/flasksong" target="_blank" >talkpython.fm/flasksong</a><br/> <br/> <strong>---== Don't be a stranger ==---</strong><br/> <strong>YouTube</strong>: <a href="https://talkpython.fm/youtube" target="_blank" ><i class="fa-brands fa-youtube"></i> youtube.com/@talkpython</a><br/> <br/> <strong>Bluesky</strong>: <a href="https://bsky.app/profile/talkpython.fm" target="_blank" >@talkpython.fm</a><br/> <strong>Mastodon</strong>: <a href="https://fosstodon.org/web/@talkpython" target="_blank" ><i class="fa-brands fa-mastodon"></i> @talkpython@fosstodon.org</a><br/> <strong>X.com</strong>: <a href="https://x.com/talkpython" target="_blank" ><i class="fa-brands fa-twitter"></i> @talkpython</a><br/> <br/> <strong>Michael on Bluesky</strong>: <a href="https://bsky.app/profile/mkennedy.codes?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >@mkennedy.codes</a><br/> <strong>Michael on Mastodon</strong>: <a href="https://fosstodon.org/web/@mkennedy" target="_blank" ><i class="fa-brands fa-mastodon"></i> @mkennedy@fosstodon.org</a><br/> <strong>Michael on X.com</strong>: <a href="https://x.com/mkennedy?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" ><i class="fa-brands fa-twitter"></i> @mkennedy</a><br/></div>

13 Mar 2026 9:17pm GMT

PyCharm

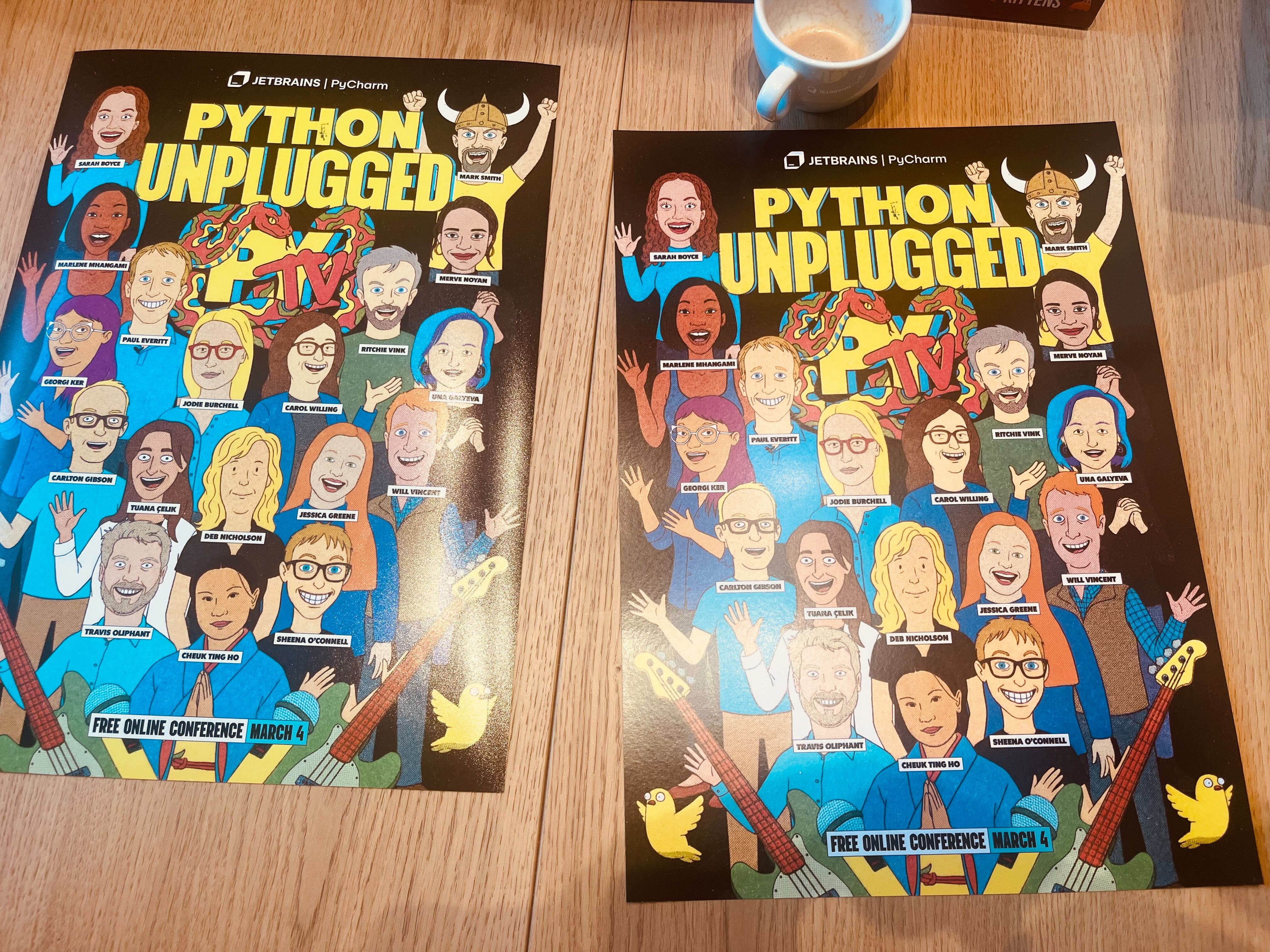

Last week marked the fruition of almost a year of hard work by the entire PyCharm team. On March 4th, 2026, we hosted Python Unplugged on PyTV, our first-ever community conference featuring a 90s music-inspired online conference for the Python community.

Python Unplugged on PyTV - Free Online Python Conference

The PyCharm team is a fixture at Python conferences globally, such as PyCon US and EuroPython, but we recognize that while attending a conference can be life-changing, the costs involved put it out of reach for many Pythonistas.

We wanted to recreate the entire Python conference experience in a digital format, complete with live talks, hallway tracks, and Q&A sessions, so anyone, anywhere in the world, could join in and participate.

And we did it! Superstar speakers from across the Python community joined us in our studio in Amsterdam, Netherlands - the country where Python was born. Some of them traveled for over 10 hours, and one even joined with their newborn baby! Travis Oliphant, of Numpy and Scipy fame, was ultimately unable to join us in person, but he kindly pre-recorded a wonderful talk and participated in a live Q&A after it, despite it being very early morning in his time zone.

Cheuk Ting Ho, Jodie Burchell, Valerie Andrianova

Cheuk Ting Ho, Jodie Burchell, Valerie Andrianova

The PyCharm team is extremely grateful for the community's support in making this happen.

The event

We livestreamed the entire event from 11am to 6:30pm CET/CEST, almost seven and a half hours of content, featuring 15 speakers, a PyLadies panel, and an ongoing quiz with prizes. Topics covered the future of Python, AI, data science, web development, and more.

Here is the complete list of speakers and timestamped links to their talks:

- Carol Willing - JupyterLab Core Developer

- Deb Nicholson - Executive Director, Python Software Foundation

- Ritchie Vink - Creator of Polars

- Travis Oliphant - Creator of NumPy

- Sarah Boyce - Django Fellow

- Sheena O'Connell - Python Software Foundation Board Member

- Marlene Mhangami - Senior Developer Advocate at Microsoft

- Carlton Gibson - Creator of multiple open-source projects in the Django ecosystem

- Tuana Çelik - Developer Relations Engineer at LlamaIndex

- Merve Noyan - Machine Learning Engineer at Hugging Face

- Paul Everitt - Developer Advocate at JetBrains

- Mark Smith - Head of Python Ecosystem at JetBrains

- Georgi Ker - Director and Fellow of the Python Software Foundation

- Una Galyeva - Head of AI at Geobear Global and PyLadies Amsterdam organizer

- Jessica Greene - Senior Machine Learning Engineer at Ecosia

The studio room with presenter's desk and Q&A table.

The studio room with presenter's desk and Q&A table.  Production meeting the day before the event

Production meeting the day before the event

We spent the afternoon doing final checks and a run-through with the studio team at Vixy Live. They were very professional and patient with us as we were working in a studio for the first time. With their help, we were confident that the event the next day would go smoothly.

Livestream day

On the day of the livestream, we arrived early to get our makeup done. The makeup artists were absolute pros, and we all looked great on camera. One of our speakers, Carol, jokingly said that she is now 20 years younger! The hosts, Jodie, Will, and Cheuk, were totally covered in '90s fashion and vibes.

Python Team Lead Jodie Burchell bringing the 90s back

Python Team Lead Jodie Burchell bringing the 90s back

We also had swag designed by our incredible marketing team, including t-shirts, stickers, posters, and tote bags.

PyTV Stickers for all participants

PyTV Stickers for all participants  PyTV Totebags

PyTV Totebags  PyTV posters

PyTV posters

Python content for everyone

After a brief opening introducing the conference and the event Discord, we began with a series of talks focused on the community, learning Python, and other hot Python topics. We also had two panels, both absolutely inspiring: one on the role of AI in open source and another featuring prominent members of PyLadies.

Following our first block of speakers, we moved on to web development-focused talks from key people involved with the Django framework. We then had a series of talks from experts across the data science and AI world, including speakers from Microsoft, Hugging Face, and LlamaIndex, who gave us up-to-date insights into open-source AI and agent-based approaches. We ended with a talk by Carol Willing, one of the most respected figures in the Python community.

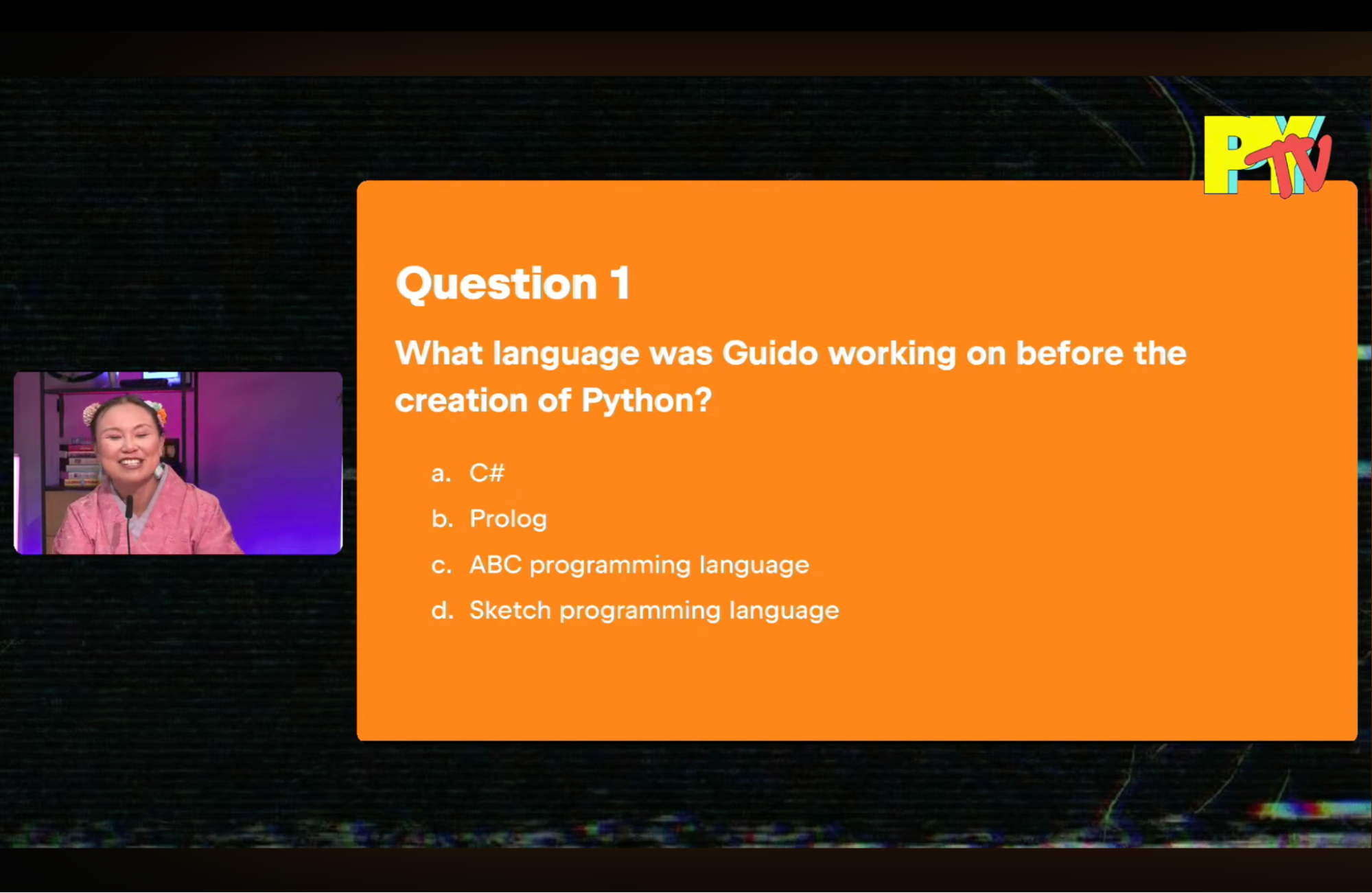

Throughout the day, we ran a quiz for the audience to test their knowledge about Python and the community. Since we had many audience members learning Python, we hope they learned some fun facts about Python through the quiz.

First of 8 questions on the Python ecosystem

First of 8 questions on the Python ecosystem  Sarah Boyce, Will Vincent, Sheena O'Connell, Carlton Gibson, Marlene Mhangami

Sarah Boyce, Will Vincent, Sheena O'Connell, Carlton Gibson, Marlene Mhangami

Next year?

Looking at the numbers, we had more than 5,500 people join us during the live stream, with most of them watching at least one talk. We've since had another 8,000 people as of this writing watch the event recording.

We'd love to do this event again next year. If you have suggestions for speakers, topics, swag, or anything else please leave it in the comments!

13 Mar 2026 4:41pm GMT

Django community aggregator: Community blog posts

Django community aggregator: Community blog posts

Django News - 21 PRs in One Week to Django Core! - Mar 13th 2026

News

The Call for Proposals for DjangoCon US 2026 has been extended one week!

DjangoCon US 2026 has extended its Call for Proposals deadline by one week to March 23 at 11 AM CDT, giving prospective speakers a little more time to submit their talk ideas.

CPython: 36 Years of Source Code

An analysis of the growth of CPython's codebase from its first commits to the present day

Releases

Python 3.15.0 alpha 7

Python 3.15.0 alpha 7 introduces explicit lazy imports, a new frozendict type, improved profiling tools, and JIT upgrades that deliver modest performance gains while development continues toward the upcoming beta.

Django Software Foundation

DSF member of the month - Theresa Seyram Agbenyegah

Theresa Seyram Agbenyegah features as DSF member of the month for March 2026, highlighting her Django community leadership and PyCon organization work.

Updates to Django

Today, "Updates to Django" is presented by Johanan from Djangonaut Space! 🚀

Last week we had 21 pull requests merged into Django by 11 different contributors - including 2 first-time contributors! Congratulations to KhadyotTakale and Lakshya Prasad for having their first commits merged into Django - welcome on board!

This week's Django highlights:

-

Fixed TypeError in deprecation warnings if Django is imported by namespace. (#36961)

-

Improved admin changelist layout for object-tools button. (#36887)

-

Fixed migrate --run-syncdb crash for existing model with truncated db_table names. (#12529)

Django Newsletter

Django Fellow Reports

Fellow Report - Jacob

Two cool features landed this week: @Antoliny0919's more standard vertical layout for inputs and labels in admin forms, and Artyom Kotovskiy's work to make RenameModel migration operations update permission names as well.

Lots of tickets triaged, reviewed, and authored!

Fellow Report - Natalia

This week had as the main attraction the security releases I issued on Tuesday (6.0.3, 5.2.12, and 4.2.29), which required the usual coordination, strong focus, and intense follow-up.

Beyond that, a significant part of the week was spent navigating the continuing wave of LLM-generated pull requests, which adds a fair amount of noise to the review queue. After prioritizing the security work, I tried to reclaim some joy in the day-to-day Fellow work by digging through long-snoozed notification emails and picking off a number of lingering tickets and PRs that had been waiting for attention.

Sponsored Link 1

The deployment service for developers and teams.

Articles

New Feature Proposal for Django - AddConstraintConcurrently

More context on a recent proposal suggesting a pair of opt-in contrib.postgres operations - AddConstraintConcurrently and RemoveConstraintConcurrently - to allow unique indexes created via UniqueConstraint to be created and dropped concurrently.

Avoiding empty strings in non-nullable Django string-based model fields

Django silently converts None values in non-nullable string fields into empty strings, but a simple CheckConstraint can enforce truly required values and prevent empty data from slipping into your database.

Buttondown - How we check every link in your email

The machinery behind Buttondown's link checker is more involved than you might expect.

The State of OpenSSL for pyca/cryptography with Alex Gaynor and Paul Kehrer

The written transcript of an interview all about Python security/cryptography, current features in cryptography, as well as some of what's coming in the future.

Year of the Snake Recap

Mariatta's review of the year showcases how prolific she was, with conferences, documentaries, ice cream selfies, and much more.

What is `self`?

Eric Matthes tackles the age-old questions that is asked many times by newcomers, but is always worth revisiting.

I Ditched Elasticsearch for Meilisearch. Here's What Nobody Tells You.

A practical deep dive into replacing Elasticsearch with Meilisearch, showing how a simpler Rust-based search engine cut costs from $120 to $14 a month while delivering faster, typo-tolerant search for typical application workloads.

Videos

From Kenya to London - Velda Kiara

The video version of Django Chat and this week's guest, Velda. We won't always do a double-feature of episodes, but Velda is always sunny and uplifting even amidst these last legs of winter.

Python Unplugged on PyTV - Free Online Python Conference

If you missed it live last week, there was a digital conference hosted by PyCharm featuring several Django speakers including Sarah Boyce (Fellow), Carlton Gibson (podcast host), and Sheena O'Connell (PSF Member). Timestamps in the description!

Podcasts

Django Chat #197: From Kenya to London with Django - Velda Kiara

Velda is a software engineer at RevSys based in London and an extremely active member of the Python and Django communities. She is a PSF Fellow, former Djangonaut, co-maintainer of django-debug-toolbar, regular conference speaker, and Microsoft MVP.

Django Job Board

Explore new opportunities this week including a Solutions Architect role at JetBrains, an Infrastructure Engineer position at the Python Software Foundation, and a Lead Backend Engineer opening at TurnTable.

Solutions Architect - Python (Client-facing) at JetBrains 🆕

Infrastructure Engineer at Python Software Foundation

Lead Backend Engineer at TurnTable

Django Newsletter

Projects

Lupus/django-lumen

Visualize your Django models as an interactive ERD diagram in the browser. No external diagram library - the diagram is pure vanilla JS + SVG rendered at request time from the live Django model registry.

paradedb/django-paradedb

Official extension to Django for use with ParadeDB.

This RSS feed is published on https://django-news.com/. You can also subscribe via email.

13 Mar 2026 3:00pm GMT

Planet Python

Planet Python

Rodrigo Girão Serrão: TIL #141 – Inspect a lazy import

Today I learned how to inspect a lazy import object in Python 3.15.

Python 3.15 comes with lazy imports and today I played with them for a minute. I defined the following module mod.py:

print("Hey!")

def f():

return "Bye!"Then, in the REPL, I could check that lazy imports indeed work:

>>> # Python 3.15

>>> lazy import mod

>>>The fact that I didn't see a "Hey!" means that the import is, indeed, lazy. Then, I wanted to take a look at the module so I printed it, but that triggered reification (going from a lazy import to a regular module):

>>> print(mod)

Hey!

<module 'mod' from '/Users/rodrigogs/Documents/tmp/mod.py'>So, I checked the PEP that introduced explicit lazy modules and turns out as soon as you reference the lazy object directly, it gets reified. But you can work around it by using globals:

>>> # Fresh 3.15 REPL

>>> lazy import mod

>>> globals()["mod"]

<lazy_import 'mod'>This shows the new class lazy_import that was added to support lazy imports!

Pretty cool, right?

13 Mar 2026 1:38pm GMT

11 Mar 2026

Django community aggregator: Community blog posts

Django community aggregator: Community blog posts

Weeknotes (2026 week 11)

Weeknotes (2026 week 11)

Last time I wrote that I seem to be publishing weeknotes monthly. Now, a quarter of a year has passed since the last entry. I do enjoy the fact that I have published more posts focused on a single topic. That said, what has been going on in open source land is certainly interesting too.

LLMs in Open Source

I have started a longer piece to think about my stance regarding using LLMs in Open Source. The argument I'm thinking about is that there's a balance between LLMs having ingested all of my published open source code and myself using them now to help myself and others again.

The happenings in the last two weeks (think Pentagon, Iran, and the bombings of schools) have again brought to the foreground the perils of using those tools. I therefore haven't been motivated to pursue this train of thought for the moment. When the upsides are somewhat questionable and tentative and the downsides are so clear and impossible to miss, it's hard to use my voice to speak in favor of these tools.

That said, all the shaming when someone uses an LLM that I see in my Mastodon feed also annoys me. I'll quote part of a post here which I liked and leave it at that for the moment:

The AI hype-cyclone is bad, but so is the anti-AI witch hunt. Commits co-authored by Claude do not mean that a project has "abandoned engineering as a serious endeavor"

[…]

Other goings-on

- Health: My back continues to improve. Some days are still bad, but the idea that the herniation may go away entirely doesn't sound totally unreasonable anymore.

- Gardening: We started weeding the garden last week. Lots to do! Being outside is fun. Weeding isn't the greatest part ever, but it's meditative.

Releases since December

- django-json-schema-editor 0.12.1: CSS fixes. I have again looked at other, more modern JSON schema editor implementations but all of them are more limited than is acceptable to act as a replacement.

- django-debug-toolbar 6.2: I haven't done much work here! Just some reviewing.

- django-content-editor 8.1: Started emitting warnings when using non-abstract base classes for plugins. Using multi table inheritance is mostly an accident and not intended in my experience when using django-content-editor, therefore we have started detecting this case and emitting system checks (warnings, not errors).

- django-imagefield 0.23.0a3: We have done some work on supporting libvips as an alternative backend to Pillow because I hoped that memory usage in Kubernetes pods might go down a bit. Results are not conclusive yet, and I'm not yet convinced the additional code complexity is worth it. Debugging and monitoring continues.

- FeinCMS 26.2.1: Released a few bugfixes. FeinCMS is still being maintained ~17 years later!

- django-auto-admin-fieldsets 0.3: Added a helper to remove fields from the fieldsets structure.

- django-tree-queries 0.23.1: Shipped a small bugfix for

{% recursetree %}which unintentionally cached children across invocations. - feincms3-downloads: Used

PATHfrom the environment instead of using a very restricted allowlist so thatconvertandpdftocairoare detected in more locations. This should help with local development for example on macOS. - django-prose-editor 0.24.1: Read the CHANGELOG; there's too much in there for a short notice.

- form-designer 0.27.3: Mosparo captcha support, bugfixes and additional translations.

- feincms3 5.5: Started using the

OrderableTreeNodefrom django-tree-queries.

11 Mar 2026 5:00pm GMT

From Kenya to London with Django - Velda Kiara

🔗 Links

- Velda at RevSys

- Velda's Substack: The Storyteller's Byte Tales

- Velda on GitHub

- Optimal Performance Over Basic as a Perfectionist with Deadlines

- More about me

- Neapolitan

📦 Projects

📚 Books

- A History of the Bible by John Barton

- Python Mastery, a course from David Beazley

- Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

🎥 YouTube

Sponsor

This episode was brought to you by Buttondown, the easiest way to start, send, and grow your email newsletter. New customers can save 50% off their first year with Buttondown using the coupon code DJANGO.

11 Mar 2026 4:00pm GMT

04 Mar 2026

Planet Twisted

Planet Twisted

Glyph Lefkowitz: What Is Code Review For?

Humans Are Bad At Perceiving

Humans are not particularly good at catching bugs. For one thing, we get tired easily. There is some science on this, indicating that humans can't even maintain enough concentration to review more than about 400 lines of code at a time..

We have existing terms of art, in various fields, for the ways in which the human perceptual system fails to register stimuli. Perception fails when humans are distracted, tired, overloaded, or merely improperly engaged.

Each of these has implications for the fundamental limitations of code review as an engineering practice:

-

Inattentional Blindness: you won't be able to reliably find bugs that you're not looking for.

-

Repetition Blindness: you won't be able to reliably find bugs that you are looking for, if they keep occurring.

-

Vigilance Fatigue: you won't be able to reliably find either kind of bugs, if you have to keep being alert to the presence of bugs all the time.

-

and, of course, the distinct but related Alert Fatigue: you won't even be able to reliably evaluate reports of possible bugs, if there are too many false positives.

Never Send A Human To Do A Machine's Job

When you need to catch a category of error in your code reliably, you will need a deterministic tool to evaluate - and, thanks to our old friend "alert fatigue" above - ideally, to also remedy that type of error. These tools will relieve the need for a human to make the same repetitive checks over and over. None of them are perfect, but:

- to catch logical errors, use automated tests.

- to catch formatting errors, use autoformatters.

- to catch common mistakes, use linters.

- to catch common security problems, use a security scanner.

Don't blame reviewers for missing these things.

Code review should not be how you catch bugs.

What Is Code Review For, Then?

Code review is for three things.

First, code review is for catching process failures. If a reviewer has noticed a few bugs of the same type in code review, that's a sign that that type of bug is probably getting through review more often than it's getting caught. Which means it's time to figure out a way to deploy a tool or a test into CI that will reliably prevent that class of error, without requiring reviewers to be vigilant to it any more.

Second - and this is actually its more important purpose - code review is a tool for acculturation. Even if you already have good tools, good processes, and good documentation, new members of the team won't necessarily know about those things. Code review is an opportunity for older members of the team to introduce newer ones to existing tools, patterns, or areas of responsibility. If you're building an observer pattern, you might not realize that the codebase you're working in already has an existing idiom for doing that, so you wouldn't even think to search for it, but someone else who has worked more with the code might know about it and help you avoid repetition.

You will notice that I carefully avoided saying "junior" or "senior" in that paragraph. Sometimes the newer team member is actually more senior. But also, the acculturation goes both ways. This is the third thing that code review is for: disrupting your team's culture and avoiding stagnation. If you have new talent, a fresh perspective can also be an extremely valuable tool for building a healthy culture. If you're new to a team and trying to build something with an observer pattern, and this codebase has no tools for that, but your last job did, and it used one from an open source library, that is a good thing to point out in a review as well. It's an opportunity to spot areas for improvement to culture, as much as it is to spot areas for improvement to process.

Thus, code review should be as hierarchically flat as possible. If the goal of code review were to spot bugs, it would make sense to reserve the ability to review code to only the most senior, detail-oriented, rigorous engineers in the organization. But most teams already know that that's a recipe for brittleness, stagnation and bottlenecks. Thus, even though we know that not everyone on the team will be equally good at spotting bugs, it is very common in most teams to allow anyone past some fairly low minimum seniority bar to do reviews, often as low as "everyone on the team who has finished onboarding".

Oops, Surprise, This Post Is Actually About LLMs Again

Sigh. I'm as disappointed as you are, but there are no two ways about it: LLM code generators are everywhere now, and we need to talk about how to deal with them. Thus, an important corollary of this understanding that code review is a social activity, is that LLMs are not social actors, thus you cannot rely on code review to inspect their output.

My own personal preference would be to eschew their use entirely, but in the spirit of harm reduction, if you're going to use LLMs to generate code, you need to remember the ways in which LLMs are not like human beings.

When you relate to a human colleague, you will expect that:

- you can make decisions about what to focus on based on their level of experience and areas of expertise to know what problems to focus on; from a late-career colleague you might be looking for bad habits held over from legacy programming languages; from an earlier-career colleague you might be focused more on logical test-coverage gaps,

- and, they will learn from repeated interactions so that you can gradually focus less on a specific type of problem once you have seen that they've learned how to address it,

With an LLM, by contrast, while errors can certainly be biased a bit by the prompt from the engineer and pre-prompts that might exist in the repository, the types of errors that the LLM will make are somewhat more uniformly distributed across the experience range.

You will still find supposedly extremely sophisticated LLMs making extremely common mistakes, specifically because they are common, and thus appear frequently in the training data.

The LLM also can't really learn. An intuitive response to this problem is to simply continue adding more and more instructions to its pre-prompt, treating that text file as its "memory", but that just doesn't work, and probably never will. The problem - "context rot" is somewhat fundamental to the nature of the technology.

Thus, code-generators must be treated more adversarially than you would a human code review partner. When you notice it making errors, you always have to add tests to a mechanical, deterministic harness that will evaluates the code, because the LLM cannot meaningfully learn from its mistakes outside a very small context window in the way that a human would, so giving it feedback is unhelpful. Asking it to just generate the code again still requires you to review it all again, and as we have previously learned, you, a human, cannot review more than 400 lines at once.

To Sum Up

Code review is a social process, and you should treat it as such. When you're reviewing code from humans, share knowledge and encouragement as much as you share bugs or unmet technical requirements.

If you must reviewing code from an LLM, strengthen your automated code-quality verification tooling and make sure that its agentic loop will fail on its own when those quality checks fail immediately next time. Do not fall into the trap of appealing to its feelings, knowledge, or experience, because it doesn't have any of those things.

But for both humans and LLMs, do not fall into the trap of thinking that your code review process is catching your bugs. That's not its job.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to my patrons who are supporting my writing on this blog. If you like what you've read here and you'd like to read more of it, or you'd like to support my various open-source endeavors, you can support my work as a sponsor!

04 Mar 2026 5:24am GMT

19 Feb 2026

Planet Twisted

Planet Twisted

Donovan Preston: Wello Horld.

Onovanday Restonpay is going to logbay here again. It's time to take back the rss-source-rss-reader web of links

19 Feb 2026 2:36am GMT

05 Jan 2026

Planet Twisted

Planet Twisted

Glyph Lefkowitz: How To Argue With Me About AI, If You Must

As you already know if you've read any of this blog in the last few years, I am a somewhat reluctant - but nevertheless quite staunch - critic of LLMs. This means that I have enthusiasts of varying degrees sometimes taking issue with my stance.

It seems that I am not going to get away from discussions, and, let's be honest, pretty intense arguments about "AI" any time soon. These arguments are starting to make me quite upset. So it might be time to set some rules of engagement.

I've written about all of these before at greater length, but this is a short post because it's not about the technology or making a broader point, it's about me. These are rules for engaging with me, personally, on this topic. Others are welcome to adopt these rules if they so wish but I am not encouraging anyone to do so.

Thus, I've made this post as short as I can so everyone interested in engaging can read the whole thing. If you can't make it through to the end, then please just follow Rule Zero.

Rule Zero: Maybe Don't

You are welcome to ignore me. You can think my take is stupid and I can think yours is. We don't have to get into an Internet Fight about it; we can even remain friends. You do not need to instigate an argument with me at all, if you think that my analysis is so bad that it doesn't require rebutting.

Rule One: No 'Just'

As I explained in a post with perhaps the least-predictive title I've ever written, "I Think I'm Done Thinking About genAI For Now", I've already heard a bunch of bad arguments. Don't tell me to 'just' use a better model, use an agentic tool, use a more recent version, or use some prompting trick that you personally believe works better. If you skim my work and think that I must not have deeply researched anything or read about it because you don't like my conclusion, that is wrong.

Rule Two: No 'Look At This Cool Thing'

Purely as a productivity tool, I have had a terrible experience with genAI. Perhaps you have had a great one. Neat. That's great for you. As I explained at great length in "The Futzing Fraction", my concern with generative AI is that I believe it is probably a net negative impact on productivity, based on both my experience and plenty of citations. Go check out the copious footnotes if you're interested in more detail.

Therefore, I have already acknowledged that you can get an LLM to do various impressive, cool things, sometimes. If I tell you that you will, on average, lose money betting on a slot machine, a picture of a slot machine hitting a jackpot is not evidence against my position.

Rule Two And A Half: Engage In Metacognition

I specifically didn't title the previous rule "no anecdotes" because data beyond anecdotes may be extremely expensive to produce. I don't want to say you can never talk to me unless you're doing a randomized controlled trial. However, if you are going to tell me an anecdote about the way that you're using an LLM, I am interested in hearing how you are compensating for the well-documented biases that LLM use tends to induce. Try to measure what you can.

Rule Three: Do Not Cite The Deep Magic To Me

As I explained in "A Grand Unified Theory of the AI Hype Cycle", I already know quite a bit of history of the "AI" label. If you are tempted to tell me something about how "AI" is really such a broad field, and it doesn't just mean LLMs, especially if you are trying to launder the reputation of LLMs under the banner of jumbling them together with other things that have been called "AI", I assure you that this will not be convincing to me.

Rule Four: Ethics Are Not Optional

I have made several arguments in my previous writing: there are ethical arguments, efficacy arguments, structuralist arguments, efficiency arguments and aesthetic arguments.

I am happy to, for the purposes of a good-faith discussion, focus on a specific set of concerns or an individual point that you want to make where you think I got something wrong. If you convince me that I am entirely incorrect about the effectiveness or predictability of LLMs in general or as specific LLM product, you don't need to make a comprehensive argument about whether one should use the technology overall. I will even assume that you have your own ethical arguments.

However, if you scoff at the idea that one should have any ethical boundaries at all, and think that there's no reason to care about the overall utilitarian impact of this technology, that it's worth using no matter what else it does as long as it makes you 5% better at your job, that's sociopath behavior.

This includes extreme whataboutism regarding things like the water use of datacenters, other elements of the surveillance technology stack, and so on.

Consequences

These are rules, once again, just for engaging with me. I have no particular power to enact broader sanctions upon you, nor would I be inclined to do so if I could. However, if you can't stay within these basic parameters and you insist upon continuing to direct messages to me about this topic, I will summarily block you with no warning, on mastodon, email, GitHub, IRC, or wherever else you're choosing to do that. This is for your benefit as well: such a discussion will not be a productive use of either of our time.

05 Jan 2026 5:22am GMT