26 Feb 2026

Planet Grep

Planet Grep

Wouter Verhelst: On Free Software, Free Hardware, and the firmware in between

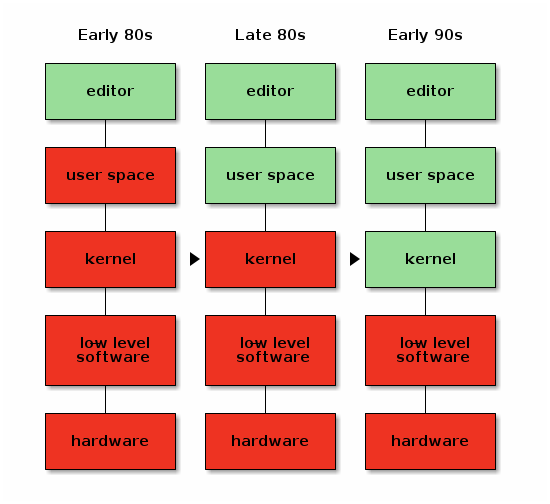

When the Free Software movement started in the 1980s, most of the world had just made a transition from free university-written software to non-free, proprietary, company-written software. Because of that, the initial ethical standpoint of the Free Software foundation was that it's fine to run a non-free operating system, as long as all the software you run on that operating system is free.

Initially this was just the editor.

But as time went on, and the FSF managed to write more and more parts of the software stack, their ethical stance moved with the times. This was a, very reasonable, pragmatic stance: if you don't accept using a non-free operating system and there isn't a free operating system yet, then obviously you can't write that free operating system, and the world won't move towards a point where free operating systems exist.

In the early 1990s, when Linus initiated the Linux kernel, the situation reached the point where the original dream of a fully free software stack was complete.

Or so it would appear.

Because, in fact, this was not the case. Computers are physical objects, composed of bits of technology that we refer to as "hardware", but in order for these bits of technology to communicate with other bits of technology in the same computer system, they need to interface with each other, usually using some form of bus protocol. These bus protocols can get very complicated, which means that a bit of software is required in order to make all the bits communicate with each other properly. Generally, this software is referred to as "firmware", but don't let that name deceive you; it's really just a bit of low-level software that is very specific to one piece of hardware. Sometimes it's written in an imperative high-level language; sometimes it's just a set of very simple initialization vectors. But whatever the case might be, it's always a bit of software.

And although we largely had a free system, this bit of low-level software was not yet free.

Initially, storage was expensive, so computers couldn't store as much data as today, and so most of this software was stored in ROM chips on the exact bits of hardware they were meant for. Due to this fact, it was easy to deceive yourself that the firmware wasn't there, because you never directly interacted with it. We knew it was there; in fact, for some larger pieces of this type of software it was possible, even in those days, to install updates. But that was rarely if ever done at the time, and it was easily forgotten.

And so, when the free software movement slapped itself on the back and declared victory when a fully free operating system was available, and decided that the work of creating a free software environment was finished, that only keeping it recent was further required, and that we must reject any further non-free encroachments on our fully free software stack, the free software movement was deceiving itself.

Because a computing environment can never be fully free if the low-level pieces of software that form the foundations of that computing environment are not free. It would have been one thing if the Free Software Foundation declared it ethical to use non-free low-level software on a computing environment if free alternatives were not available. But unfortunately, they did not.

In fact, something very strange happened.

In order for some free software hacker to be able to write a free replacement for some piece of non-free software, they obviously need to be able to actually install that theoretical free replacement. This isn't just a random thought; in fact it has happened.

Now, it's possible to install software on a piece of rewritable storage such as flash memory inside the hardware and boot the hardware from that, but if there is a bug in your software -- not at all unlikely if you're trying to write software for a piece of hardware that you don't have documentation for -- then it's not unfathomable that the replacement piece of software will not work, thereby reducing your expensive piece of technology to something about as useful as a paperweight.

Here's the good part.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the bits of technology that made up computers became so complicated, and the storage and memory available to computers so much larger and cheaper, that it became economically more feasible to create a small, tiny, piece of software stored in a ROM chip on the hardware, with just enough knowledge of the bus protocol to download the rest from the main computer.

This is awesome for free software. If you now write a replacement for the non-free software that comes with the hardware, and you make a mistake, no wobbles! You just remove power from the system, let the DRAM chips on the hardware component fully drain, return power, and try again. You might still end up with a brick of useless silicon if some of the things you sent to your technology make it do things that it was not designed to do and therefore you burn through some critical bits of metal or plastic, but the chance of this happening is significantly lower than the chance of you writing something that impedes the boot process of the piece of hardware and you are unable to fix it because the flash is overwritten. There is anecdotal evidence that there are free software hackers out there who do so. So, yay, right? You'd think the Free Software foundation would jump at the possibility to get more free software? After all, a large part of why we even have a Free Software Foundation in the first place, was because of some piece of hardware that was misbehaving, so you would think that the foundation's founders would understand the need for hardware to be controlled by software that is free.

The strange thing, what has always been strange to me, is that this is not what happened.

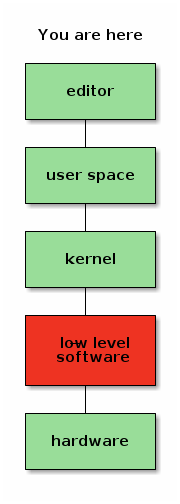

The Free Software Foundation instead decided that non-free software on ROM or flash chips is fine, but non-free software -- the very same non-free software, mind -- that touches the general storage device that you as a user use, is not. Never mind the fact that the non-free software is always there, whether it sits on your storage device or not.

Misguidedness aside, if some people decide they would rather not update the non-free software in their hardware and use the hardware with the old and potentially buggy version of the non-free software that it came with, then of course that's their business.

Unfortunately, it didn't quite stop there. If it had, I wouldn't have written this blog post.

You see, even though the Free Software Foundation was about Software, they decided that they needed to create a hardware certification program. And this hardware certification program ended up embedding the strange concept that if something is stored in ROM it's fine, but if something is stored on a hard drive it's not. Same hardware, same software, but different storage. By that logic, Windows respects your freedom as long as the software is written to ROM. Because this way, the Free Software Foundation could come to a standstill and pretend they were still living in the 90s.

An unfortunate result of the "RYF" program is that it means that companies who otherwise would have been inclined to create hardware that was truly free, top to bottom, are now more incentivised by the RYF program to create hardware in which the non-free low-level software can't be replaced.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world did not pretend to still be living in the nineties, and free hardware communities now exist. Because of how the FSF has marketed themselves out of the world, these communities call themselves "Open Hardware" communities, rather than "Free Hardware" ones, but the principle is the same: the designs are there, if you have the skill you can modify it, but you don't have to.

In the mean time, the open hardware community has evolved to a point where even CPUs are designed in the open, which you can design your own version of.

But not all hardware can be implemented as RISC-V, and so if you want a full system that builds RISC-V you may still need components of the system that were originally built for other architectures but that would work with RISC-V, such as a network card or a GPU. And because the FSF has done everything in their power to disincentivise people who would otherwise be well situated to build free versions of the low-level software required to support your hardware, you may now be in the weird position where we seem to have somehow skipped a step.

My own suspicion is that the universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.

-- J.B.S. Haldane

(comments for this post will not pass moderation. Use your own blog!)

26 Feb 2026 2:45pm GMT

Dries Buytaert: Skiing in Saint-Gervais, France

Last week, we went on a ski trip in Saint-Gervais, France. For the first time, Axl wasn't with us. He's off at university now, and his school breaks no longer line up with Stan's. So Stan and I had a lot of father-son time on the slopes.

Our friends Alexis and Héloïse were also on the trip with us, and Alexis captured this short video one of the days. I love it. Thank you, Alexis!

26 Feb 2026 2:45pm GMT

Dries Buytaert: My Web3 site survived four years of neglect

Four years ago, I published my first Web3 webpage using IPFS and ENS. I uploaded a simple "Hello World" HTML file, pointed dries.eth at it, and left it there. Two years later, I found it still running.

I haven't touched it since. Today, on the experiment's four-year anniversary, I checked again. It's still up at dries.eth.limo. Four years of total neglect, and the page loads just fine.

When I checked two years ago, every service I used was still operational. I called that "really encouraging". That optimism aged poorly.

Today, half the services have shut down, restricted access, or pivoted entirely:

-

Fleek, a platform I used to pin my content, shut down its hosting service on January 31, 2026. They pivoted to AI.

-

Infura was acquired by MetaMask and closed its IPFS service to new users.

-

Web3.storage rebranded to Storacha, and dropped IPFS pinning altogether.

Of the original services, Pinata is still focused on IPFS. I logged in and my "Hello World" HTML file is still there. And eth.limo, the ENS gateway that lets anyone access .eth sites in a normal browser, still works.

Technically robust, commercially fragile

IPFS content exists only as long as someone chooses to host it. In 2022, my HTML file was pinned on Fleek, Pinata, Infura, and a friend's node. Today, it comes down to Pinata's free tier. My web3 page is hanging by a thread.

That sounds fragile, and in one sense it is. But the protocol is working as designed. IPFS doesn't promise permanence. It promises that content is addressable, verifiable, and can be kept alive by anyone who cares enough to pin it.

The durability of content on IPFS scales with how much people care about it. No one really cares about my "Hello World" page, so it's not being pinned. If this were dissident journalism or censored speech, people would likely pin it.

If you run an IPFS node and want to help keep my page alive, feel free to pin it: ipfs pin add bafybeibbkhmln7o4ud6an4qk6bukcpri7nhiwv6pz6ygslgtsrey2c3o3q.

Of course, I could make it more robust myself by pinning it on additional services or running my own node. Instead, I relied on third parties. With no node of my own, I'm entirely dependent on pinning services and other users to keep it alive.

The real story isn't fragility. It's economics. There may simply not be enough demand for decentralized storage to support a healthy market of providers. Companies keep entering, failing to find a business model, and pivoting away.

Traditional hosting is cheap, reliable, and familiar. The people who need censorship resistance are a narrow group, and everyone else has little reason to switch, myself included. And to be fair, replacing everyday web hosting was probably never IPFS's goal.

I still love IPFS as a protocol and the ideas behind it. But it feels like the ecosystem around it is commercially thin, and getting thinner.

I've written before about the idea of a RAID for web content. Rather than relying on a single system, the goal is redundancy across multiple layers. I'd like to experiment more with IPFS and make it one of those layers.

Browser support got worse, not better

In 2022, mainstream browsers didn't support ENS or IPFS natively, except for Brave. Brave included a built-in IPFS node that could resolve ipfs:// and ipns:// addresses directly.

In August 2024, Brave removed that integration. Fewer than 0.1% of users had ever used it, and the support costs were too high.

Chrome, Firefox, and Safari still don't support ENS or IPFS natively. A Firefox issue for adding IPFS support has been open since 2017, with no plans to implement it. The IPFS community continues pushing for browser standards work, but native protocol support seems like a long way off.

Today, the easiest way to visit a .eth site is still through a gateway like eth.limo. You append .limo to the ENS name and visit it in any browser. It works, but it's a centralized bridge to a decentralized system, which is a little ironic.

Gas fees dropped 99%

Not everything got worse. In my original post, I called out the cost of updating an ENS record as a major barrier. When content changes on IPFS, its hash changes too. To keep dries.eth pointing to the latest version, that new address has to be written to Ethereum, which costs gas.

Updating my content on Ethereum cost me $11.69 in 2022 and $4.08 in 2024. If I wanted to update it today, it would cost roughly one cent.

Average Ethereum gas prices now sit around 0.03 to 0.05 Gwei, compared to 30 to 50 Gwei when I first set this up. That is roughly a thousand times cheaper.

Two things drove this.

First, Ethereum roughly doubled the computation it can process per block over 2025. Validators gradually raised the gas limit, and the Fusaka upgrade in December formally pushed it from 30 million to 60 million.

Second, many applications migrated to Layer 2 networks. These are separate blockchains that batch up transactions and settle them back to Ethereum in bulk. As traffic moved off the main chain, congestion and fees dropped further.

The impact on ENS is dramatic. Just this month, ENS Labs cancelled its planned Layer 2 blockchain called "Namechain" because Ethereum's main network got so inexpensive that the Layer 2 became unnecessary. Nick Johnson, ENS co-founder and lead developer, noted that subsidizing 100% of all ENS transactions at current gas prices would cost about $10,000 per year.

A mixed scorecard

Four years in, the technology is better than ever but the market around it is worse. The IPFS protocol seems sound. ENS records are permanent. Gas fees have nearly vanished. But the commercial ecosystem for decentralized hosting has steadily thinned.

I wrote in 2022 that "IPFS and ENS offer limited value to most website owners, but tremendous value to a very narrow subset". Four years later, that assessment holds true.

AI also absorbed most of the tech industry's attention and capital. Web3 funding dropped sharply. Fleek's pivot from IPFS hosting to AI inference feels symbolic.

Will I keep the experiment going? Of course. But it's probably time to add a few more pins and stop relying on free tiers. The protocols don't need my help. The ecosystem apparently does.

26 Feb 2026 2:45pm GMT

25 Feb 2026

Planet Debian

Planet Debian

Sahil Dhiman: Publicly Available NKN Data Traffic Graphs

National Knowledge Network (NKN) is one of India's main National Research and Educational Network (NREN). The other being the less prevalent Education and Research Network (ERNET).

This post grew out of this Mastodon thread where I kept on adding various public graphs (from various global research and educational entities) that peer or connect with NKN. This was to get some purview about traffic data between them and NKN.

CERN

CERN, birthplace of the World Wide Web (WWW) and home of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

- Graph - https://monit-grafana-open.cern.ch/d/XoND3VQ4k/nkn?orgId=16&from=now-30d&to=now&timezone=browser&var-source=raw&var-bin=5m

- Connection seems to be 2x10 G through CERNLight.

India participates in the LHCONE project, which carries LHC data over these links for scientific research purposes. This presentation from Vikas Singhal from Variable Energy Cyclotron Centre (VECC), Kolkata, at the 8th Asian Tier Center Forum in 2024 gives some details.

GÉANT

GÉANT is pan European Union's collaboration of NRENs.

- Graph https://public-brian.geant.org/d/ZyVgYFgVk/nkn?orgId=5&from=now-30d&to=now

- NKN connects at Amsterdam POP.

- From the 2016 press release from GÉANT, NKN seems to have 2x10 G capacity towards GÉANT. Things might have changed since.

LEARN

Lanka Education and Research Network (LEARN) is Sri Lanka's NREN.

- Graph https://kirigal.learn.ac.lk/traffic/details.php?desc=slt-b1-new&data_id=1788&data_id_v6=&sub_bw=1000&name=National%20Knowledge%20Network%20of%20India%20(1G)&swap_inout=

- Connection seems to be 1 G.

NORDUnet

NREN for Nordic countries.

I couldn't find any public live data transfer graphs from NKN side. If you know any other graphs, do let me know.

25 Feb 2026 1:38pm GMT

24 Feb 2026

Planet Debian

Planet Debian

Louis-Philippe Véronneau: Montreal's Debian & Stuff - February 2026

Our Debian User Group met on February 22nd for our first meeting of the year!

Here's what we did:

pollo:

- reviewed and merged Lintian contributions:

- released lintian version

2.130.0 - upstreamed a patch for python-wilderness, fixed a few things and released version

0.1.10-3 - updated python-clevercsv to version

0.8.4 - updated python-mediafile to version

0.14.0

lelutin:

- opened up a RFH for co-maintenance for smokeping and added Marc Haber who responded really quickly to the call

- with mjeanson's help: prepped and uploaded a new smokeping version to release pending work

- opened a NM request to become DM

viashimo:

- fixed freshrss timer

- updated freshrss

- installed new navidrome container

- configured backups for new host (beelink mini s12)

tvaz:

- did NM work

- learned more about debusine and tested it

- uploaded antimony to debusine

- (co-)convinced lelutin to apply for DM (yay!)

lavamind:

- worked on autopkgtests for a new version of jruby

Pictures

This time around, we held our meeting at cégep du Vieux Montréal, the college where I currently work. Here is the view we had:

We also ordered some delicious pizzas from Pizzeria dei Compari, a nice pizzeria on Saint-Denis street that's been there forever.

Some of us ended up grabbing a drink after the event at l'Amère à boire, a pub right next to the venue, but I didn't take any pictures.

24 Feb 2026 9:45pm GMT

John Goerzen: Screen Power Saving in the Linux Console

I just made up a Debian trixie setup that has no need for a GUI. In fact, I rarely use the text console either. However, because the machine is dual boot and also serves another purpose, it's connected to my main monitor and KVM switch.

The monitor has three inputs, and when whatever display it's set to goes into powersave mode, it will seek out another one that's active and automatically switch to it.

You can probably see where this is heading: it's really inconvenient if one of the inputs never goes into powersave mode. And, of course, it wastes energy.

I have concluded that the Linux text console has lost the ability to enter powersave mode after an inactivity timeout. It can still do screen blanking - setting every pixel to black - but that is a distinct and much less useful thing.

You can do a lot of searching online that will tell you what to do. Almost all of it is wrong these days. For instance, none of these work:

- Anything involving vbetool. This is really, really old advice.

- Anything involving xset, unless you're actually running a GUI, which is not the point of this post.

- Anything involving setterm or the kernel parameters video=DPMS or consoleblank.

- Anything involving writing to paths under /sys, such as ones ending in dpms.

Why is this?

Well, we are on at least the third generation of Linux text console display subsystems. (Maybe more than 3, depending on how you count.) The three major ones were:

- The VGA text console

- fbdev

- DRI/KMS

As I mentioned recently in my post about running an accurate 80×25 DOS-style console on modern Linux, the VGA text console mode is pretty much gone these days. It relied on hardware rendering of the text fonts, and that capability simply isn't present on systems that aren't PCs - or even on PCs that are UEFI, which is most of them now.

fbdev, or a framebuffer console under earlier names, has been in Linux since the late 1990s. It was the default for most distros until more recently. It supported DPMS powersave modes, and most of the instructions you will find online reference it.

Nowadays, the DRI/KMS system is used for graphics. Unfortunately, it is targeted mainly at X11 and Wayland. It is also used for the text console, but things like DPMS-enabled timeouts were never implemented there.

You can find some manual workarounds - for instance, using ddcutil or similar for an external monitor, or adjusting the backlight files under /sys on a laptop. But these have a number of flaws - making unwanted brightness adjustments, and not automatically waking up on keypress among them.

My workaround

I finally gave up and ran apt-get install xdm. Then in /etc/X11/xdm/Xsetup, I added one line:

xset dpms 0 0 120

Now the system boots into an xdm login screen, and shuts down the screen after 2 minutes of inactivity. On the rare occasion where I want a text console from it, I can switch to it and it won't have a timeout, but I can live with that.

Thus, quite hopefully, concludes my series of way too much information about the Linux text console!

24 Feb 2026 2:22pm GMT

16 Feb 2026

Planet Lisp

Planet Lisp

Joe Marshall: binary-compose-left and binary-compose-right

If you have a unary function F, you can compose it with function G, H = F ∘ G, which means H(x) = F(G(x)). Instead of running x through F directly, you run it through G first and then run the output of G through F.

If F is a binary function, then you either compose it with a unary function G on the left input: H = F ∘left G, which means H(x, y) = F(G(x), y) or you compose it with a unary function G on the right input: H = F ∘right G, which means H(x, y) = F(x, G(y)).

(binary-compose-left f g) = (λ (x y) (f (g x) y)) (binary-compose-right f g) = (λ (x y) (f x (g y)))

We could extend this to trinary functions and beyond, but it is less common to want to compose functions with more than two inputs.

binary-compose-right comes in handy when combined with fold-left. This identity holds

(fold-left (binary-compose-right f g) acc lst) <=> (fold-left f acc (map g lst))

but the right-hand side is less efficient because it requires an extra pass through the list to map g over it before folding. The left-hand side is more efficient because it composes g with f on the fly as it folds, so it only requires one pass through the list.

16 Feb 2026 9:35pm GMT

11 Feb 2026

Planet Lisp

Planet Lisp

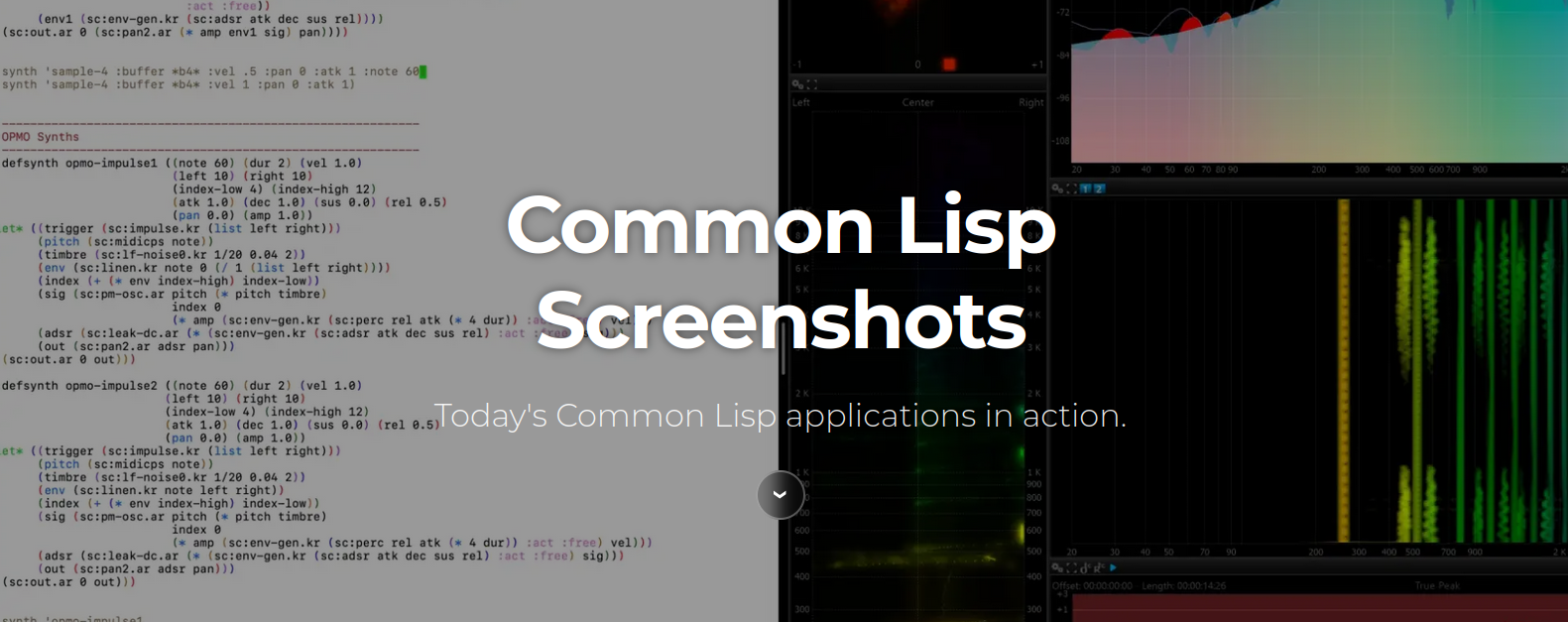

vindarel: 🖌️ Lisp screenshots: today's Common Lisp applications in action

I released a hopefully inspiring gallery:

lisp-screenshots.org

We divide the showcase under the categories Music, Games, Graphics and CAD, Science and industry, Web applications, Editors and Utilities.

Of course:

"Please don't assume Lisp is only useful for...

thank you ;)

For more example of companies using CL in production, see this list (contributions welcome, of course).

Don't hesitate to share a screenshot of your app! It can be closed source and yourself as the sole user, as long as it as some sort of a GUI, and you use it. Historical success stories are for another collection.

The criteria are:

- built in Common Lisp

- with some sort of a graphical interface

- targeted at end users

- a clear reference, anywhere on the web, by email to me or simply as a comment here, that it is built in CL.

Details:

- it can be web applications whose server side is CL, even if the JS/HTML is classical web tech.

- no CLI interfaces. A readline app is OK but hey, we can do better.

- it can be closed-source or open-source, commercial, research or a personal software

- regarding "end users": I don't see how to include a tool like CEPL, but I did include a screen of LispWorks.

- bonus point if it is developed in a company (we want it on https://github.com/azzamsa/awesome-lisp-companies/), be it a commercial product or an internal tool.

You can reach us on GitHub discussions, by email at (reverse "gro.zliam@stohsneercs+leradniv") and in the comments.

Best,

11 Feb 2026 10:35pm GMT

07 Feb 2026

Planet Lisp

Planet Lisp

Joe Marshall: Vibe Coded Scheme Interpreter

Mark Friedman just released his Scheme-JS interpreter which is a Scheme with transparent JavaScript interoperability. See his blog post at furious ideas.

This interpreter apparently uses the techniques of lightweight stack inspection - Mark consulted me a bit about that hack works. I'm looking forward to seeing the vibe coded architecture.

07 Feb 2026 12:28am GMT

29 Jan 2026

FOSDEM 2026

FOSDEM 2026

Join the FOSDEM Treasure Hunt!

Are you ready for another challenge? We're excited to host the second yearly edition of our treasure hunt at FOSDEM! Participants must solve five sequential challenges to uncover the final answer. Update: the treasure hunt has been successfully solved by multiple participants, and the main prizes have now been claimed. But the fun doesn't stop here. If you still manage to find the correct final answer and go to Infodesk K, you will receive a small consolation prize as a reward for your effort. If you're still looking for a challenge, the 2025 treasure hunt is still unsolved, so舰

29 Jan 2026 11:00pm GMT

26 Jan 2026

FOSDEM 2026

FOSDEM 2026

Guided sightseeing tours

If your non-geek partner and/or kids are joining you to FOSDEM, they may be interested in spending some time exploring Brussels while you attend the conference. Like previous years, FOSDEM is organising sightseeing tours.

26 Jan 2026 11:00pm GMT

Call for volunteers

With FOSDEM just a few days away, it is time for us to enlist your help. Every year, an enthusiastic band of volunteers make FOSDEM happen and make it a fun and safe place for all our attendees. We could not do this without you. This year we again need as many hands as possible, especially for heralding during the conference, during the buildup (starting Friday at noon) and teardown (Sunday evening). No need to worry about missing lunch at the weekend, food will be provided. Would you like to be part of the team that makes FOSDEM tick?舰

26 Jan 2026 11:00pm GMT