28 Feb 2026

Planet Mozilla

Planet Mozilla

The Servo Blog: January in Servo: preloads, better forms, details styling, and more!

Servo 0.0.5 is here, bringing with it lots of improvements in web platform features. Some highlights:

- <link rel=preload> (@TimvdLippe, @jdm, #40059)

- <style blocking> and <link blocking> (@TimvdLippe, #42096)

- <img align> (@mrobinson, #42220)

- <select disabled> (@simonwuelker, #42036)

- OGG files can now be played in <audio> (@jdm, #41789)

- 'cursor-color' (@mrobinson, #41976)

- 'content: <image>' works on all elements (@andreubotella, #41480)

- '::details-content' on <details> (@lukewarlow, #42107)

- ':open' on <details> (@lukewarlow, #42195)

- ':active' on <input type=button> (@mrobinson, #42095)

- Origin API (@WaterWhisperer, #41712)

- MouseEvent.detail (@mrobinson, #41833)

- Request.keepalive (@TimvdLippe, @WaterWhisperer, #41457, #41811)

- Cyclic imports, import attributes, and JSON modules (@Gae24, #41779)

- navigator.sendBeacon() is enabled by default (@TimvdLippe, #41694)

https_proxy,HTTPS_PROXY, andNO_PROXY(@Narfinger, #41689)- ML-KEM, ML-DSA, and AES-OCB in Crypto (@kkoyung, #41604, #41617, #41615, #41627, #41628, #41647, #41659, #41676, #41791, #41822, #41813, #41829)

Web APIs

Servo now plays OGG media inside <audio> elements (@jdm, #41789)! We disabled this feature many years ago due to bugs in GStreamer, our media playback engine, but those bugs have since been fixed.

We now support non-px sizes for width and height attributes in <svg> elements (@rodio, #40761).

Inactive documents will now correctly reject fullscreen mode changes (@stevennovaryo, #42068).

We've enabled support for the navigator.sendBeacon() by default (@TimvdLippe, #41694); the dom_navigator_sendbeacon_enabled preference has been removed. As part of this work, we implemented the keepalive feature of the Request API (@TimvdLippe, @WaterWhisperer, #41457, #41811).

That's not all for network-related improvements! Quota errors from the fetchLater() API provide more details (@TimvdLippe, #41665), and fetch response body promises now reject when invalid gzip content is encountered (@arayaryoma, #39438). Meanwhile, EventSource connections will no longer endlessly reconnect for permanent failures (@WaterWhisperer, #41651, #42137), and now use the correct 'Last-Event-Id' header when reconnecting (@WaterWhisperer, #42103). Finally, Servo will create PerformanceResourceTiming entries for requests that returned unsuccessful responses (@bellau, #41804).

There has been lots of work related to navigating pages and loading iframes. We process URL fragments more consistently when navigating via window.location (@TimvdLippe, #41805, #41834), and allow evaluating javascript: URLs when a document's domain has been modified (@jdm, #41969). XML documents loaded in an <iframe> no longer inherit their encoding from the parent document (@simonwuelker, #41637).

We're also made it possible to use blob: URLs from inside 'about:blank' and 'about:srcdoc' documents (@jdm, #41966, #42104). Finally, constructed documents (e.g. new Document()) now inherit the origin and domain of the document that created them (@TimvdLippe, #41780), and we implemented the new Origin API (@WaterWhisperer, #41712).

Servo's mixed content protections are steadily increasing. Insecure requests (e.g. HTTP) originating from <iframe> elements can now be upgraded to secure protocols (@WaterWhisperer, #41661), and redirected requests now check the most recent URL when determining if the protocol is secure (@WaterWhisperer, #41832).

<style blocking> and <link blocking> can now be used to block rendering while loading stylesheets that are added dynamically (@TimvdLippe, #42096), and stylesheets loaded when parsing the document will block the document 'load' event more consistently (@TimvdLippe, @mrobinson, #41986, #41987, #41988, #41973). We also fire the 'error' event if a fetched stylesheet response is invalid (@TimvdLippe, @mrobinson, #42037).

Servo now leads other browsers in support for new Web Cryptography algorithms! This includes full support for ML-KEM (@kkoyung, #41604, #41617, #41615, #41627), ML-DSA (@kkoyung, #41628, #41647, #41659, #41676), and AES-OCB (@kkoyung, #41791, #41822, #41813, #41829), plus improvements to AES-GCM (@kkoyung, #41950). Additionally, the error messages returned by many Crypto APIs are now more detailed (@PaulTreitel, @danilopedraza, #41964, #41468, #41902).

JS module loading received a lot of attention - we've improved support for cyclic imports (@Gae24, #41779), import attributes (@Gae24, #42185), and JSON modules (@Gae24, @jdm, #42138).

Additionally, the <link rel=preload> attribute now triggers preload fetch operations that can improve page load speeds (@TimvdLippe, @jdm, #40059).

IndexedDB support continues to make progress, though for now the feature is disabled by default (--pref dom_indexeddb_enabled). This month we gained improvements to connection queues (@gterzian, #41500, #42053) and request granularity (@gterzian, #41933).

We were accidentally persisting SessionStorage data beyond the current session, but this has been corrected (@arihant2math, #41326).

Text input fields have received a lot of love this month. Clicking in an input field will position the cursor accordingly (@mrobinson, @jdm, @Loirooriol, #41906, #41974, #41931), as will clicking past the end of a multiline input (@mrobinson, @Loirooriol, #41909). Selecting text with the mouse in input fields works (@mrobinson, #42049), and double and triple clicks now toggle selections (@mrobinson, #41926). Finally, we fixed a bug causing the input caret to be hidden in <input> elements inside of Shadow DOM content (@stevennovaryo, #42233).

'cursor-color' is respected when rendering the input cursor (@mrobinson, #41976), and newlines can no longer be pasted into single line inputs (@mrobinson, #41934). Finally, we fixed a panic when focusing a text field that is disabled (@mrobinson, #42078), as well as panics in APIs like HTMLInputElement.setRangeText() that confused bytes and UTF-8 character indices (@mrobinson, #41588).

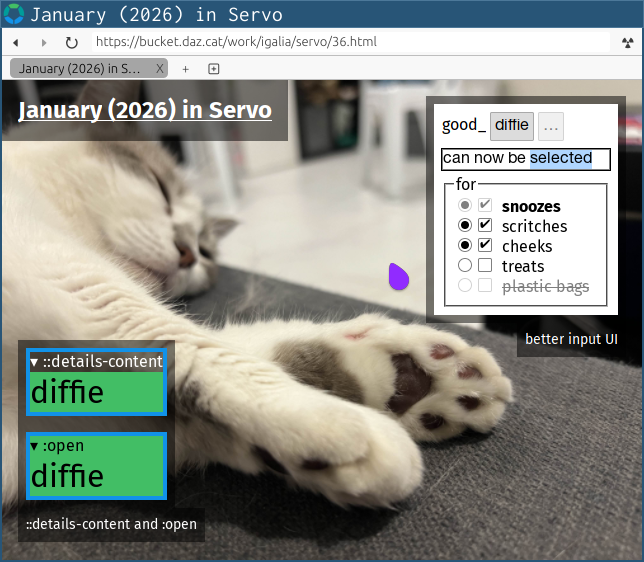

We also made time to improve form controls! The default styling of many controls received some care (@mrobinson, #42085), while <input type=button> can now be styled with the ':active' pseudo-class (@mrobinson, #42095). Conversely, disabled <select> elements can no longer be activated (@simonwuelker, #42036).

Mouse events triggered by the embedder are more complete; MouseEvent.detail correctly reports the click count for 'mouseup' and 'mousedown' events (@mrobinson, #41833), and many other members are now consistent with other mouse events (@mrobinson, #42013).

Performing a pinch zoom on mobile is now reflected in the VisualViewport API (@stevennovaryo, #41754), though for now the feature is disabled by default (--pref dom_visual_viewport_enabled).

We've changed the behaviour of Web APIs that use the [Clamp] annotation (such as Blob.slice()). The previous implementation would cast floating point values to their integer equivalents, but the standard requires more specific rounding logic (@Taym95, #41640).

The RGBA8 constant is now available in WebGL 1 rendering contexts; it was previously only available in WebGL 2 contexts (@simonwuelker, #42048).

Fonts were another area of focus this month. Loading web fonts from file: URLs works as expected (@TimvdLippe, #41714), as does using web fonts within Shadow DOM content (@minghuaw, #42151). Each web font request now creates a PerformanceResourceTiming entry (@lumi-me-not, #41784). Servo supports font variations as of November 2025, so as of this month, the FontFace constructor no longer ignores the 'font-variation-settings' property (@muse254, #41968).

Cursive scripts now ignore the 'letter-spacing' CSS property (@mrobinson, #42165), and we significantly reduced the time and memory required when rendering non-ASCII text (@mrobinson, @Loirooriol, #42105, #42162) and when text nodes share the same font (@mrobinson, #41876).

CSS

There were lots of improvements to block layout algorithms (@Loirooriol, #41492, #41624, #41632, #41655, #41652, #41683). These often affect pages where a block element (such as a <div>) exists within some other layout mode (such as an inline <span>, or a flexbox context), and fixes like these ensure Servo matches the output of other browsers.

Elements with scrollable overflow can be scrolled more consistently, even with CSS transforms applied to them (@stevennovaryo, #41707, #42005).

You can now use 'content: <image>' on any element (@andreubotella, #41480). Generated image content used to only work with pseudo-elements, but that restriction no longer applies.

<details> elements can now be styled with the '::details-content' pseudo-element (@lukewarlow, #42107), as well as the ':open' pseudo-class (@lukewarlow, #42195).

CSS styles now inherit correctly through 'display: contents' as well as <slot> elements in Shadow DOM content (@longvatrong111, @Loirooriol, @mrobinson, #41855).

'overflow-clip-margin' now works correctly when 'border-radius' is present (@Loirooriol, #41967).

We fixed bugs involving text inside flexbox elements: they now use consistent baselines for alignment (@lukewarlow, @mrobinson, #42038), and style updates are propagated to the text correctly (@mrobinson, #41951).

<img align> now aligns the image as expected (@mrobinson, #42220).

'word-break: keep-all' now prevents line breaks in CJK text (@RichardTjokroutomo, #42088).

We also fixed some bugs involving floats, collapsing margins, and phantom line boxes (@Loirooriol, #41812), which sound much cooler than they actually are.

Finally, we upgraded our Stylo dependency to the latest changes as of January 1 2026 (@Loirooriol, #41916, #41696). Stylo powers our CSS parsing and style resolution engine, and this upgrade improves support for parsing color functions like 'color-mix()', and improves our CSS animations and transitions for borders and overflow clipping.

Automation and introspection

Last month Servo gained support for HTTP proxies. We now support HTTPS proxies as well (@Narfinger, #41689), which can be configured with the https_proxy or HTTPS_PROXY environment variables, or the network_https_proxy_uri preference. In addition, the NO_PROXY environment variable or the network_http_no_proxy preference can disable any proxy for particular domains.

Our developer tools integration continues to improve. Worker globals are now categorized correctly in the UI (@atbrakhi, #41929), and the Sources panel is populated for very short documents (@atbrakhi, #41983). Servo will report console messages that were logged before the developer tools are opened (@eerii, @mrobinson, #41895). Finally, we fixed a panic when selecting nodes in the layout inspector that have no style information (@eerii, #41800).

We're working towards supporting pausing in the JS debugger (@eerii, @atbrakhi, @jdm, #42007), and breakpoints can be toggled through the UI (@eerii, @atbrakhi, #41925, #42154). While the debugger is paused, hovering over JS objects will report the object's properties for builtin JS classes (@eerii, @atbrakhi, #42186). Stay tuned for more JS debugging updates in next month's blog post!

Servo's WebDriver server is also maturing. Evaluating a synchronous script that returns a Promise will wait until that promise settles (@yezhizhen, #41823). 'touchmove' events are fired for pointer actions when a button is pressed (@yezhizhen, #41801), and 'touchcancel' events are fired for canceled pointer action items (@yezhizhen, #41937). Finally, any pointer actions that would trigger duplicate 'mousemove' events are silently discarded (@mrobinson, #42034).

Element Clear commands now test whether the element is interactable (@yezhizhen, #42124). Now a null script execution timeout value will never trigger a timeout (@yezhizhen, #42184), and synthesized 'pointermove' events have a consistent pointerId value (@yezhizhen, #41726).

Embedding

You can now cross-compile Servo using Windows as the host (@yezhizhen, #41748).

We've pinned all git dependencies to specific revisions, to reduce the risk of build failures (@Narfinger, #42029). We intend to eventually forbid git dependencies in Servo libraries, which will help unblock releasing Servo on crates.io.

SiteDataManager now has a new clear_site_data() method to clear all stored data for a particular host (@janvarga, #41618, #41709, #41852).

Our nightly testing UI, servoshell, now respects any customized installation path on Windows (@yezhizhen, #41653). We fixed a crash in the Android app when pausing the application (@NiklasMerz, #41827). Additionally, clicking inside a webview in the desktop app will remove focus from any browser UI (@mrobinson, #42080).

We've laid more groundwork towards exposing accessibility tree information from webviews (@delan, @lukewarlow, @alice, #41924). There's nothing to test yet, but keep an eye on our tracking issue if you want to be notified when nightly builds are ready for testing!

Stability & performance

We've converted many uses of IPC channels in the engine to channels that are more efficient when multiprocess mode is disabled (@Narfinger, @jdm, @sagudev, @mrobinson, #41178, #41071, #41733, #41806, #41380, #41809, #41774, #42032, #42033, #41412). Since multiprocess mode is not yet enabled by default (--multiprocess), this is a significant boost to Servo's everyday performance.

Servo now sets a socket timeout for HTTP connections (@Narfinger, @mrobinson, #41710). This is controlled by the network_connection_timeout preference, and defaults to 15 seconds.

Each instance of Servo now starts four fewer threads (@Narfinger, #41740). Any network operations that trigger a synchronous UI operation (such as an HTTP authentication prompt) no longer blocks other network tasks from completing (@Narfinger, @jdm, #41965, #41857).

It's said that one of the hardest problems in computer science is cache invalidation. We improved the memory usage of dynamic inline SVG content by evicting stale SVG tree data from a cache (@TomRCummings, #41675). Meanwhile, we added a new cache to reduce memory usage and improve rendering performance for pages with animating images (@Narfinger, #41956).

Servo's JS engine now accounts for 2D and 3D canvas-related memory usage when deciding how often to perform garbage collection (@sagudev, #42180). This can reduce the risk of out-of-memory (OOM) errors on pages that create large numbers of short-lived WebGL or WebGPU objects.

To reduce the risk of panics involving the JS engine integration, we're continuing to use the Rust type system to make certain kinds of dynamic borrow failures impossible (@sagudev, #41692, #41782, #41756, #41808, #41879, #41878, #41955, #41971, #42123). We also continue to identify and forbid code patterns that can trigger rare crashes when garbage collection happens while destroying webviews (@willypuzzle, #41717, #41783, #41911, #41911, #41977, #41984, #42243).

This month also brought fixes for panics in parallel layout (@mrobinson, #42026), WebGPU (@WaterWhisperer, #42050), <link> fetching (@jdm, #42208), Element.attachShadow() (@mrobinson, #42237), text input methods (@mrobinson, #42240), Web Workers when the developer tools are active (@mrobinson, #42159), IndexedDB (@gterzian, #41960), and asynchronous session history updates (@mrobinson, #42238).

Node.compareDocumentPosition() is now more efficient (@webbeef, #42260), and selections in text inputs no longer require a full page layout (@mrobinson, @Loirooriol, #41963).

Donations

Thanks again for your generous support! We are now receiving 7007 USD/month (−1.4% over December) in recurring donations. This helps us cover the cost of our speedy CI and benchmarking servers, one of our latest Outreachy interns, and funding maintainer work that helps more people contribute to Servo.

Servo is also on thanks.dev, and already 33 GitHub users (+3 over December) that depend on Servo are sponsoring us there. If you use Servo libraries like url, html5ever, selectors, or cssparser, signing up for thanks.dev could be a good way for you (or your employer) to give back to the community.

We now have sponsorship tiers that allow you or your organisation to donate to the Servo project with public acknowlegement of your support. A big thanks from Servo to our newest Bronze Sponsor: str4d! If you're interested in this kind of sponsorship, please contact us at join@servo.org.

Use of donations is decided transparently via the Technical Steering Committee's public funding request process, and active proposals are tracked in servo/project#187. For more details, head to our Sponsorship page.

Conference talks and blogs

There were two talks about Servo at FOSDEM 2026 (videos and slides here):

-

Implementing Streams Spec in Servo - Taym Haddadi (@taym95) described the challenges of implementing the Streams Standard.

-

The Servo project and its impact on the web platform - Manuel Rego (@rego) highlighted the ways that Servo has shaped the web platform and contributed to web standards since it started in 2012.

28 Feb 2026 12:00am GMT

27 Feb 2026

Planet Mozilla

Planet Mozilla

Mozilla Localization (L10N): Localizer Spotlight: Marcelo

About You

My name is Marcelo Poli. I live in Argentina, and I speak Spanish and English. I started contributing to Mozilla localization with Phoenix 0.3 - 24 years ago.

Mozilla Localization Journey

Q: How did you first get involved in localizing Mozilla products?

A: There was a time when alternative browsers were incompatible with many websites. "Best with IE" appeared everywhere. Then Mozilla was reborn with Phoenix. It was just the browser - unlike Mozilla Suite (the old name for SeaMonkey) - and it was the best option.

At first, it was only available in English, so I searched and found an opportunity to localize my favorite browser. There were already some Spanish localization for the Suite, and that became the base for my work. It took me two releases to complete it, and Phoenix 0.3 shipped with a full language pack - the first Spanish localization in Phoenix history.

The most amazing part was that Mozilla let me do it.

Q: Do you have a favorite product? Do you use the ones you localize regularly?

A: Firefox is always my favorite. Thunderbird comes second - it's the simplest and most powerful email software. Firefox has been my default browser since the Phoenix era, and since many Mozilla products are connected, working on one often makes you want to contribute to others as well.

Q: What moments stand out from your localization journey?

A: Being part of the Firefox 1.0 release was incredible. The whole world was talking about the new browser, and my localization was part of it.

Another unforgettable moment was seeing my name - along with hundreds of others - on the Mozilla Monument in San Francisco.

Q: Have you shared your work with family and friends?

A: Yes. I usually say, "Try this, it's better," and many times they agree. Sometimes I have to explain the concept of free software. When they say, "But I didn't pay for the other browsers," I use the classic explanation: "Free as in freedom and free as in free beer."

I wear Mozilla T-shirts, but I don't brag about managing the Argentinian localization. Still, some tech-savvy friends have found my name in the credits.

Community & Collaboration

Q: How does the Argentinian localization community work together today?

A: In the beginning, the Suite localization, Firefox localization, and the Argentinian community were separate. Mozilla encouraged us to join forces, and I eventually became the l10n manager.The community has grown and shrunk over time. Right now it's smaller, but localization remains the most active part, keeping products up to date. We stay in touch through an old mailing list, Matrix, and direct messages. I've also participated in many community events, although living far from Buenos Aires limits how often I can attend.

Q: How do you coordinate translation, review, and testing?

A: We're a small group, which actually makes coordination easier. Since we contribute in our free time, even small contributions matter, and three people can approve strings at any time.

We test using Nightly as our main browser. Priorities are set in Pontoon - once the five-star products are complete, we move on to others. Usually, the number of untranslated strings is small, so it's manageable.

Q: How has your role evolved over time?

A: The old Mozilla folks - the "original cast," you could say - were essential in the early days. Before collaborative tools existed, I explained DTD and properties file structures to others. Some contributors had strong language skills but less technical background.

Since the Phoenix years, I've been responsible for es-AR localization. At first, I worked alone; later others joined. Today, I hold the manager title in Pontoon. As Uncle Ben once said, "With great power comes great responsibility," so I check Pontoon daily.

Q: What best practices would you share with other localizers?

A: Pontoon is easy to use. The key is respecting terminology and staying consistent across the localization.

If you find a typo or a better phrasing, suggest it directly in Pontoon. You don't need to contact a manager, and it doesn't matter how small the change is. Every contribution matters - even if it isn't approved.

Professional Background & Skills

Q: What is your professional background, and how has it helped your localization work?

A: I studied programming, so I understand software structure and how it works. That helped a lot in the early days when localization required editing files directly - especially dealing with encoding and file structure.

Knowledge of web development also helped with Developer Tools strings, and as a heavy user, I'm familiar with the terminology for almost everything you can do in software.

Q: What have you gained beyond translation?

A: Mozilla allows you to be part of something global - meeting people from different countries and learning how similar or different we are. Through community events and hackathons, I learned how to collaborate internationally. As a side effect, I became more fluent speaking English face to face than I expected.

Q: After so many years, what keeps you motivated?

A: My main motivation is being able to use Mozilla products in my own language. Mozilla is unique in having four Spanish localization. Most projects offer only one for all Spanish-speaking countries - or at best, one for Spain and one for Latin America.

I'm not the most social person in the community, so recruiting isn't really my role. The best way I motivate others is simply by continuing to work on the projects. Many years ago, I contributed a few strings to Ubuntu localization - maybe they're still there.

Fun Facts

I was a radio DJ for many years - sometimes just playing music, sometimes talking about it.

Paraphrasing Sting, I was born in the '60s and witnessed the first home computers like Texas Instruments and Commodore. My first personal computer was pre-Windows, with text-based screens, and I used Netscape Navigator on dial-up.

I still prefer a big screen over a cellphone and mechanical keyboards over on-screen ones. These days, I'm learning how to build mobile apps.

27 Feb 2026 4:31pm GMT

Niko Matsakis: How Dada enables internal references

In my previous Dada blog post, I talked about how Dada enables composable sharing. Today I'm going to start diving into Dada's permission system; permissions are Dada's equivalent to Rust's borrow checker.

Goal: richer, place-based permissions

Dada aims to exceed Rust's capabilities by using place-based permissions. Dada lets you write functions and types that capture both a value and things borrowed from that value.

As a fun example, imagine you are writing some Rust code to process a comma-separated list, just looking for entries of length 5 or more:

let list: String = format!("...something big, with commas...");

let items: Vec<&str> = list

.split(",")

.map(|s| s.trim()) // strip whitespace

.filter(|s| s.len() > 5)

.collect();

One of the cool things about Rust is how this code looks a lot like some high-level language like Python or JavaScript, but in those languages the split call is going to be doing a lot of work, since it will have to allocate tons of small strings, copying out the data. But in Rust the &str values are just pointers into the original string and so split is very cheap. I love this.

On the other hand, suppose you want to package up some of those values, along with the backing string, and send them to another thread to be processed. You might think you can just make a struct like so…

struct Message {

list: String,

items: Vec<&str>,

// ----

// goal is to hold a reference

// to strings from list

}

…and then create the list and items and store them into it:

let list: String = format!("...something big, with commas...");

let items: Vec<&str> = /* as before */;

let message = Message { list, items };

// ----

// |

// This *moves* `list` into the struct.

// That in turn invalidates `items`, which

// is borrowed from `list`, so there is no

// way to construct `Message`.

But as experienced Rustaceans know, this will not work. When you have borrowed data like an &str, that data cannot be moved. If you want to handle a case like this, you need to convert from &str into sending indices, owned strings, or some other solution. Argh!

Dada's permissions use places, not lifetimes

Dada does things a bit differently. The first thing is that, when you create a reference, the resulting type names the place that the data was borrowed from, not the lifetime of the reference. So the type annotation for items would say ref[list] String1 (at least, if you wanted to write out the full details rather than leaving it to the type inferencer):

let list: given String = "...something big, with commas..."

let items: given Vec[ref[list] String] = list

.split(",")

.map(_.trim()) // strip whitespace

.filter(_.len() > 5)

// ------- I *think* this is the syntax I want for closures?

// I forget what I had in mind, it's not implemented.

.collect()I've blogged before about how I would like to redefine lifetimes in Rust to be places as I feel that a type like ref[list] String is much easier to teach and explain: instead of having to explain that a lifetime references some part of the code, or what have you, you can say that "this is a String that references the variable list".

But what's also cool is that named places open the door to more flexible borrows. In Dada, if you wanted to package up the list and the items, you could build a Message type like so:

class Message(

list: String

items: Vec[ref[self.list] String]

// ---------

// Borrowed from another field!

)

// As before:

let list: String = "...something big, with commas..."

let items: Vec[ref[list] String] = list

.split(",")

.map(_.strip()) // strip whitespace

.filter(_.len() > 5)

.collect()

// Create the message, this is the fun part!

let message = Message(list.give, items.give)Note that last line - Message(list.give, items.give). We can create a new class and move list into it along with items, which borrows from list. Neat, right?

OK, so let's back up and talk about how this all works.

References in Dada are the default

Let's start with syntax. Before we tackle the Message example, I want to go back to the Character example from previous posts, because it's a bit easier for explanatory purposes. Here is some Rust code that declares a struct Character, creates an owned copy of it, and then gets a few references into it.

struct Character {

name: String,

class: String,

hp: u32,

}

let ch: Character = Character {

name: format!("Ferris"),

class: format!("Rustacean"),

hp: 22

};

let p: &Character = &ch;

let q: &String = &p.name;

The Dada equivalent to this code is as follows:

class Character(

name: String,

klass: String,

hp: u32,

)

let ch: Character = Character("Tzara", "Dadaist", 22)

let p: ref[ch] Character = ch

let q: ref[p] String = p.nameThe first thing to note is that, in Dada, the default when you name a variable or a place is to create a reference. So let p = ch doesn't move ch, as it would in Rust, it creates a reference to the Character stored in ch. You could also explicitly write let p = ch.ref, but that is not preferred. Similarly, let q = p.name creates a reference to the value in the field name. (If you wanted to move the character, you would write let ch2 = ch.give, not let ch2 = ch as in Rust.)

Notice that I said let p = ch "creates a reference to the Character stored in ch". In particular, I did not say "creates a reference to ch". That's a subtle choice of wording, but it has big implications.

References in Dada are not pointers

The reason I wrote that let p = ch "creates a reference to the Character stored in ch" and not "creates a reference to ch" is because, in Dada, references are not pointers. Rather, they are shallow copies of the value, very much like how we saw in the previous post that a shared Character acts like an Arc<Character> but is represented as a shallow copy.

So where in Rust the following code…

let ch = Character { ... };

let p = &ch;

let q = &ch.name;

…looks like this in memory…

# Rust memory representation

Stack Heap

───── ────

┌───► ch: Character {

│ ┌───► name: String {

│ │ buffer: ───────────► "Ferris"

│ │ length: 6

│ │ capacity: 12

│ │ },

│ │ ...

│ │ }

│ │

└──── p

│

└── q

in Dada, code like this

let ch = Character(...)

let p = ch

let q = ch.namewould look like so

# Dada memory representation

Stack Heap

───── ────

ch: Character {

name: String {

buffer: ───────┬───► "Ferris"

length: 6 │

capacity: 12 │

}, │

.. │

} │

│

p: Character { │

name: String { │

buffer: ───────┤

length: 6 │

capacity: 12 │

... │

} │

} │

│

q: String { │

buffer: ───────────────┘

length: 6

capacity: 12

}

Clearly, the Dada representation takes up more memory on the stack. But note that it doesn't duplicate the memory in the heap, which tends to be where the vast majority of the data is found.

Dada talks about values not references

This gets at something important. Rust, like C, makes pointers first-class. So given x: &String, x refers to the pointer and *x refers to its referent, the String.

Dada, like Java, goes another way. x: ref String is a String value - including in memory representation! The difference between a given String, shared String, and ref String is not in their memory layout, all of them are the same, but they differ in whether they own their contents.2

So in Dada, there is no *x operation to go from "pointer" to "referent". That doesn't make sense. Your variable always contains a string, but the permissions you have to use that string will change.

In fact, the goal is that people don't have to learn the memory representation as they learn Dada, you are supposed to be able to think of Dada variables as if they were all objects on the heap, just like in Java or Python, even though in fact they are stored on the stack.3

Rust does not permit moves of borrowed data

In Rust, you cannot move values while they are borrowed. So if you have code like this that moves ch into ch1…

let ch = Character { ... };

let name = &ch.name; // create reference

let ch1 = ch; // moves `ch`

…then this code only compiles if name is not used again:

let ch = Character { ... };

let name = &ch.name; // create reference

let ch1 = ch; // ERROR: cannot move while borrowed

let name1 = name; // use reference again

…but Dada can

There are two reasons that Rust forbids moves of borrowed data:

- References are pointers, so those pointers may become invalidated. In the example above,

namepoints to the stack slot forch, so ifchwere to be moved intoch1, that makes the reference invalid. - The type system would lose track of things. Internally, the Rust borrow checker has a kind of "indirection". It knows that

chis borrowed for some span of the code (a "lifetime"), and it knows that the lifetime in the type ofnameis related to that lifetime, but it doesn't really know thatnameis borrowed fromchin particular.4

Neither of these apply to Dada:

- Because references are not pointers into the stack, but rather shallow copies, moving the borrowed value doesn't invalidate their contents. They remain valid.

- Because Dada's types reference actual variable names, we can modify them to reflect moves.

Dada tracks moves in its types

OK, let's revisit that Rust example that was giving us an error. When we convert it to Dada, we find that it type checks just fine:

class Character(...) // as before

let ch: given Character = Character(...)

let name: ref[ch.name] String = ch.name

// -- originally it was borrowed from `ch`

let ch1 = ch.give

// ------- but `ch` was moved to `ch1`

let name1: ref[ch1.name] = name

// --- now it is borrowed from `ch1`Woah, neat! We can see that when we move from ch into ch1, the compiler updates the types of the variables around it. So actually the type of name changes to ref[ch1.name] String. And then when we move from name to name1, that's totally valid.

In PL land, updating the type of a variable from one thing to another is called a "strong update". Obviously things can get a bit complicated when control-flow is involved, e.g., in a situation like this:

let ch = Character(...)

let ch1 = Character(...)

let name = ch.name

if some_condition_is_true() {

// On this path, the type of `name` changes

// to `ref[ch1.name] String`, and so `ch`

// is no longer considered borrowed.

ch1 = ch.give

ch = Character(...) // not borrowed, we can mutate

} else {

// On this path, the type of `name`

// remains unchanged, and `ch` is borrowed.

}

// Here, the types are merged, so the

// type of `name` is `ref[ch.name, ch1.name] String`.

// Therefore, `ch` is considered borrowed here.Renaming lets us call functions with borrowed values

OK, let's take the next step. Let's define a Dada function that takes an owned value and another value borrowed from it, like the name, and then call it:

fn character_and_name(

ch1: given Character,

name1: ref[ch1] String,

) {

// ... does something ...

}We could call this function like so, as you might expect:

let ch = Character(...)

let name = ch.name

character_and_name(ch.give, name)So…how does this work? Internally, the type checker type-checks a function call by creating a simpler snippet of code, essentially, and then type-checking that. It's like desugaring but only at type-check time. In this simpler snippet, there are a series of let statements to create temporary variables for each argument. These temporaries always have an explicit type taken from the method signature, and they are initialized with the values of each argument:

// type checker "desugars" `character_and_name(ch.give, name)`

// into more primitive operations:

let tmp1: given Character = ch.give

// --------------- -------

// | taken from the call

// taken from fn sig

let tmp2: ref[tmp1.name] String = name

// --------------------- ----

// | taken from the call

// taken from fn sig,

// but rewritten to use the new

// temporariesIf this type checks, then the type checker knows you have supplied values of the required types, and so this is a valid call. Of course there are a few more steps, but that's the basic idea.

Notice what happens if you supply data borrowed from the wrong place:

let ch = Character(...)

let ch1 = Character(...)

character_and_name(ch, ch1.name)

// --- wrong place!This will fail to type check because you get:

let tmp1: given Character = ch.give

let tmp2: ref[tmp1.name] String = ch1.name

// --------

// has type `ref[ch1.name] String`,

// not `ref[tmp1.name] String`Class constructors are "just" special functions

So now, if we go all the way back to our original example, we can see how the Message example worked:

class Message(

list: String

items: Vec[ref[self.list] String]

)Basically, when you construct a Message(list, items), that's "just another function call" from the type system's perspective, except that self in the signature is handled carefully.

This is modeled, not implemented

I should be clear, this system is modeled in the dada-model repository, which implements a kind of "mini Dada" that captures what I believe to be the most interesting bits. I'm working on fleshing out that model a bit more, but it's got most of what I showed you here.5 For example, here is a test that you get an error when you give a reference to the wrong value.

The "real implementation" is lagging quite a bit, and doesn't really handle the interesting bits yet. Scaling it up from model to real implementation involves solving type inference and some other thorny challenges, and I haven't gotten there yet - though I have some pretty interesting experiments going on there too, in terms of the compiler architecture.6

This could apply to Rust

I believe we could apply most of this system to Rust. Obviously we'd have to rework the borrow checker to be based on places, but that's the straight-forward part. The harder bit is the fact that &T is a pointer in Rust, and that we cannot readily change. However, for many use cases of self-references, this isn't as important as it sounds. Often, the data you wish to reference is living in the heap, and so the pointer isn't actually invalidated when the original value is moved.

Consider our opening example. You might imagine Rust allowing something like this in Rust:

struct Message {

list: String,

items: Vec<&{self.list} str>,

}

In this case, the str data is heap-allocated, so moving the string doesn't actually invalidate the &str value (it would invalidate an &String value, interestingly).

In Rust today, the compiler doesn't know all the details of what's going on. String has a Deref impl and so it's quite opaque whether str is heap-allocated or not. But we are working on various changes to this system in the Beyond the & goal, most notably the Field Projections work. There is likely some opportunity to address this in that context, though to be honest I'm behind in catching up on the details.

-

I'll note in passing that Dada unifies

strandStringinto one type as well. I'll talk in detail about how that works in a future blog post. ↩︎ -

This is kind of like C++ references (e.g.,

String&), which also act "as if" they were a value (i.e., you writes.foo(), nots->foo()), but a C++ reference is truly a pointer, unlike a Dada ref. ↩︎ -

This goal was in part inspired by a conversation I had early on within Amazon, where a (quite experienced) developer told me, "It took me months to understand what variables are in Rust". ↩︎

-

I explained this some years back in a talk on Polonius at Rust Belt Rust, if you'd like more detail. ↩︎

-

No closures or iterator chains! ↩︎

-

As a teaser, I'm building it in async Rust, where each inference variable is a "future" and use "await" to find out when other parts of the code might have added constraints. ↩︎

27 Feb 2026 10:20am GMT