26 Feb 2026

LXer Linux News

LXer Linux News

Cloudflare experiment ports most of Next.js API 'in one week' with AI

Uses Vite and Claude to sidestep Vercel lock-in with a new open source build toolA Cloudflare engineer says he has implemented 94 percent of the Next.js API by directing Anthropic's Claude, spending about $1,100 on tokens.…

26 Feb 2026 1:38am GMT

OpenZFS 2.4.1 Released With Linux 6.19 Compatibility, Many Fixes

Following the big OpenZFS 2.4 release back in December, OpenZFS 2.4.1 was released overnight to ship support for the latest Linux 6.19 stable kernel plus a variety of different bug fixes...

26 Feb 2026 12:07am GMT

25 Feb 2026

LXer Linux News

LXer Linux News

When it Comes to Firmware, the FSF and Its Founder RMS Won the Argument (But Not the Fight, Yet)

People who have long defamed Richard Stallman (RMS) do not want us to have computer security, so they brand back doors "security".

25 Feb 2026 10:35pm GMT

Linuxiac

Linuxiac

Wireshark 4.6.4 Packet Analyzer Fixes USB HID Memory Exhaustion

Wireshark 4.6.4 network protocol analyzer resolves three security vulnerabilities, including a USB HID memory exhaustion flaw.

25 Feb 2026 10:35pm GMT

Linux Kernel LTS Support Extended for Multiple Releases

The Linux kernel project has extended support for several active LTS branches, with new projected end-of-life dates through 2027 and 2028.

25 Feb 2026 10:16pm GMT

Caddy 2.11.1 Web Server Released With Automatic ECH Key Rotation

Caddy 2.11.1 introduces six security patches, automatic ECH key rotation, enhanced reverse proxy behavior, and additional improvements.

25 Feb 2026 9:39pm GMT

LXer Linux News

LXer Linux News

Thunderbird 148 Email Client Improves Accessibility in Various Tree Views

Following the release of Firefox 148, the Mozilla Thunderbird open-source email, news, chat, calendar, and addressbook client has been updated today to version 148.

25 Feb 2026 9:04pm GMT

Bcachefs creator insists his custom LLM is female and 'fully conscious'

It's not chatbot psychosis, it's 'math and engineering and neuroscience'The latest project to start talking about using LLMs to assist in development is experimental Linux copy-on-write file system bcachefs.…

25 Feb 2026 7:32pm GMT

Arm & Linaro Launch New "CoreCollective" Consortium - With Backing From AMD & Others

The embargo just lifted on an interesting new industry consortium... CoreCollective. The CoreCollective consortium is focused on open collaboration in the Arm software ecosystem and to a large extent what Linaro has already been doing for the past decade and a half. Interestingly though with CoreCollective for open collaboration in the Arm software ecosystem, AMD is now onboard as a founding member along with various other vendors...

25 Feb 2026 6:01pm GMT

Linuxiac

Linuxiac

React Moves to the Linux Foundation With Launch of the React Foundation

React and React Native will now operate under the newly formed React Foundation, hosted by the Linux Foundation and backed by major industry members.

25 Feb 2026 5:26pm GMT

LXer Linux News

LXer Linux News

Firefox 148 adds master switch for browser bot bother

While Thunderbird 148 improves MS Exchange support and sign-on securityIt's not the only new feature in Firefox 148 yet one thing is very definitely the big news: the global off switch for its AI features that the company announced earlier this month is now included.…

25 Feb 2026 4:29pm GMT

LLVM/Clang 22 Compiler Officially Released With Many Improvements

LLVM/Clang 22.1 was released overnight as the first stable release of the LLVM 22 series. This is a nice, feature-packaged half-year update to this prominent open-source compiler stack with many great refinements...

25 Feb 2026 8:36am GMT

Linuxiac

Linuxiac

OpenZFS 2.4.1 Released with Linux 6.19 Compatibility and FreeBSD Fixes

OpenZFS 2.4.1 adds Linux 6.19 support, improves FreeBSD compatibility, and delivers dozens of stability and build fixes across platforms.

25 Feb 2026 8:32am GMT

LXer Linux News

LXer Linux News

Atom E3950 Powers WINSYSTEMS SBC-ZETA-3950 Rugged Mini SBC

WINSYSTEMS' SBC-ZETA-3950 is a rugged mini single board computer based on the Intel Atom Apollo Lake E3950, designed for industrial and space-constrained applications. It combines a COM Express Mini Type 10 module with a rugged carrier board in an 84 x 55 mm form factor. The SBC-ZETA-3950 uses the quad-core Intel Atom E3950 processor running […]

25 Feb 2026 7:05am GMT

Wine 11.3 Released with Mono 11 and VKD3D 1.19 Upgrade

Wine 11.3 brings Mono 11.0, VKD3D 1.19, better DirectSound, and 30 bug fixes to improve how Windows apps and games run on Linux.

25 Feb 2026 5:33am GMT

Rogue devs of sideloaded Android apps beg for freedom from Google's verification regime

37 groups urge the company to drop ID checks for apps distributed outside PlaySoon, developers who just want to make Android apps for sideloading will have to register with Google. Thirty-seven technology companies, nonprofits, and civil society groups think that the Chocolate Factory should keep its nose out of third-party app stores and have asked its leadership to reconsider.…

25 Feb 2026 4:02am GMT

LibreOffice Online Project Reopened With New Community Focus

The Document Foundation has revived LibreOffice Online, resuming development after formally reversing its 2022 decision to freeze the project.

25 Feb 2026 2:30am GMT

Google Cloud N4 Series Benchmarks: Google Axion vs. Intel Xeon vs. AMD EPYC Performance

Google Cloud recently launched their N4A series powered by their in-house Axion ARM64 processors. In that launch-day benchmarking last month was looking at how the N4A with Axion compared to their prior-generation ARM64 VMs powered by Ampere Altra. There were dramatic generational gains, but how does the N4A stand up to the AMD EPYC and Intel Xeon instances? Here are some follow-up benchmarks I had done to explore the N4A performance against the Intel Xeon N4 and AMD EPYC N4D series.

25 Feb 2026 12:59am GMT

24 Feb 2026

LXer Linux News

LXer Linux News

Apache NetBeans 29 Released with Java, PHP, and Git Enhancements

Apache NetBeans 29 cross-platform IDE released with Java performance improvements, PHP fixes, and updated Git integration.

24 Feb 2026 11:27pm GMT

Ardour 9.2 Open-Source DAW Released with MIDI Note Chasing and Duplication

Ardour 9.2 has been released today as the latest stable version of this powerful, free, cross-platform, and open-source digital audio workstation (DAW) software for GNU/Linux, macOS, and Windows systems.

24 Feb 2026 9:56pm GMT

Linuxiac

Linuxiac

LibreOffice Online Project Reopened With New Community Focus

The Document Foundation has revived LibreOffice Online, resuming development after formally reversing its 2022 decision to freeze the project.

24 Feb 2026 9:48pm GMT

Lutris 0.5.21 Adds Steam Sniper Runtime and New Console Emulators

Lutris 0.5.21 introduces support for Valve's Sniper runtime, adds ShadPS4 and Xenia runners, and improves GPU detection on Linux systems.

24 Feb 2026 9:21pm GMT

LXer Linux News

LXer Linux News

KDE Plasma 6.6.1 Is Out to Improve Custom Tiling, Networks Widget, and More

The KDE Project released today KDE Plasma 6.6.1 as the first maintenance update to the latest KDE Plasma 6.6 desktop environment series with an initial batch of improvements and bug fixes.

24 Feb 2026 8:24pm GMT

Linuxiac

Linuxiac

Wine 11.3 Released with Mono 11 and VKD3D 1.19 Upgrade

Wine 11.3 brings Mono 11.0, VKD3D 1.19, better DirectSound, and 30 bug fixes to improve how Windows apps and games run on Linux.

24 Feb 2026 7:39pm GMT

COSMIC Desktop 1.0.8 Improves Files, Terminal, and Wi-Fi Dialog Behavior

COSMIC Desktop 1.0.8 brings improvements to the file manager, updates to the terminal, fixes for the Wi-Fi dialog, and better overall stability.

24 Feb 2026 6:15pm GMT

Mozilla Thunderbird 148 Released with EWS Improvements

Mozilla Thunderbird 148, an open-source email client, is out with PKCE authentication for Yahoo and AOL and improved Exchange support.

24 Feb 2026 5:21pm GMT

19 Feb 2026

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Pete Zaitcev: Meanwhile in space

ODCs (Orbital Data Centers - zaitcev) will happen. The incentives are aligned from too many directions for them not to. But if you're still debating whether datacenters in space "make sense," you've missed the point.

The real story is a technology revolution hiding in plain sight. Access to space has transformed over the last decade. Space and terrestrial infrastructure are converging into a single global system. ... Whether any particular infrastructure bet succeeds in the near term matters far less than the fact that the underlying transformation is structural and self-reinforcing.

19 Feb 2026 2:55am GMT

Pete Zaitcev: The end of MinIO

Someone wrote about the collapse of MinIO (as an open-source project):

The CNCF badge isn't a safety net. MinIO was a CNCF-associated project. That association didn't prevent any of this. The CNCF doesn't control the licensing or business decisions of associated projects. If your risk model assumes that CNCF membership means long-term stability, MinIO is your counterexample.

Swift is not mentioned among the possible alternative by the author.

19 Feb 2026 2:46am GMT

16 Feb 2026

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Greg Kroah-Hartman: Linux CVE assignment process

As described previously, the Linux kernel security team does not identify or mark or announce any sort of security fixes that are made to the Linux kernel tree. So how, if the Linux kernel were to become a CVE Numbering Authority (CNA) and responsible for issuing CVEs, would the identification of security fixes happen in a way that can be done by a volunteer staff? This post goes into the process of how kernel fixes are currently automatically assigned to CVEs, and also the other "out of band" ways a CVE can be issued for the Linux kernel project.

16 Feb 2026 12:00am GMT

13 Feb 2026

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Dave Airlie (blogspot): drm subsystem AI patch review

This topic came up at kernel maintainers summit and some other groups have been playing around with it, particularly the BPF folks, and Chris Mason's work on kernel review prompts[1] for regressions. Red Hat have asked engineers to investigate some workflow enhancements with AI tooling, so I decided to let the vibecoding off the leash.

My main goal:

- Provide AI led patch review for drm patches

- Don't pollute the mailing list with them at least initially.

This led me to wanting to use lei/b4 tools, and public-inbox. If I could push the patches with message-ids and the review reply to a public-inbox I could just publish that and point people at it, and they could consume it using lei into their favorite mbox or browse it on the web.

I got claude to run with this idea, and it produced a project [2] that I've been refining for a couple of days.

I started with trying to use Chris' prompts, but screwed that up a bit due to sandboxing, but then I started iterating on using them and diverged.

The prompts are very directed at regression testing and single patch review, the patches get applied one-by-one to the tree, and the top patch gets the exhaustive regression testing. I realised I probably can't afford this, but it's also not exactly what I want.

I wanted a review of the overall series, but also a deeper per-patch review. I didn't really want to have to apply them to a tree, as drm patches are often difficult to figure out the base tree for them. I did want to give claude access to a drm-next tree so it could try apply patches, and if it worked it might increase the review, but if not it would fallback to just using the tree as a reference.

Some holes claude fell into, claude when run in batch mode has limits on turns it can take (opening patch files and opening kernel files for reference etc), giving it a large context can sometimes not leave it enough space to finish reviews on large patch series. It tried to inline patches into the prompt before I pointed out that would be bad, it tried to use the review instructions and open a lot of drm files, which ran out of turns. In the end I asked it to summarise the review prompts with some drm specific bits, and produce a working prompt. I'm sure there is plenty of tuning left to do with it.

Anyways I'm having my local claude run the poll loop every so often and processing new patches from the list. The results end up in the public-inbox[3], thanks to Benjamin Tissoires for setting up the git to public-inbox webhook.

I'd like for patch submitters to use this for some initial feedback, but it's also something that you should feel free to ignore, but I think if we find regressions in the reviews and they've been ignored, then I'll started suggesting it stronger. I don't expect reviewers to review it unless they want to. It was also suggested that perhaps I could fold in review replies as they happen into another review, and this might have some value, but I haven't written it yet. If on the initial review of a patch there is replies it will parse them, but won't do it later.

[1] https://github.com/masoncl/review-prompts

[2] https://gitlab.freedesktop.org/airlied/patch-reviewer

[3] https://lore.gitlab.freedesktop.org/drm-ai-reviews/

13 Feb 2026 6:56am GMT

06 Feb 2026

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Brendan Gregg: Why I joined OpenAI

The staggering and fast-growing cost of AI datacenters is a call for performance engineering like no other in history; it's not just about saving costs - it's about saving the planet. I have joined OpenAI to work on this challenge directly, with an initial focus on ChatGPT performance. The scale is extreme and the growth is mind-boggling. As a leader in datacenter performance, I've realized that performance engineering as we know it may not be enough - I'm thinking of new engineering methods so that we can find bigger optimizations than we have before, and find them faster. It's the opportunity of a lifetime and, unlike in mature environments of scale, it feels as if there are no obstacles - no areas considered too difficult to change. Do anything, do it at scale, and do it today.

Why OpenAI exactly? I had talked to industry experts and friends who recommended several companies, especially OpenAI. However, I was still a bit cynical about AI adoption. Like everyone, I was being bombarded with ads by various companies to use AI, but I wondered: was anyone actually using it? Everyday people with everyday uses? One day during a busy period of interviewing, I realized I needed a haircut (as it happened, it was the day before I was due to speak with Sam Altman).

Mia the hairstylist got to work, and casually asked what I do for a living. "I'm an Intel fellow, I work on datacenter performance." Silence. Maybe she didn't know what datacenters were or who Intel was. I followed up: "I'm interviewing for a new job to work on AI datacenters." Mia lit up: "Oh, I use ChatGPT all the time!" While she was cutting my hair - which takes a while - she told me about her many uses of ChatGPT. (I, of course, was a captive audience.) She described uses I hadn't thought of, and I realized how ChatGPT was becoming an essential tool for everyone. Just one example: She was worried about a friend who was travelling in a far-away city, with little timezone overlap when they could chat, but she could talk to ChatGPT anytime about what the city was like and what tourist activities her friend might be doing, which helped her feel connected. She liked the memory feature too, saying it was like talking to a person who was living there.

I had previously chatted to other random people about AI, including a realtor, a tax accountant, and a part-time beekeeper. All told me enthusiastically about their uses of ChatGPT; the beekeeper, for example, uses it to help with small business paperwork. My wife was already a big user, and I was using it more and more, e.g. to sanity-check quotes from tradespeople. Now my hairstylist, who recognized ChatGPT as a brand more readily than she did Intel, was praising the technology and teaching me about it. I stood on the street after my haircut and let sink in how big this was, how this technology has become an essential aide for so many, how I could lead performance efforts and help save the planet. Joining OpenAI might be the biggest opportunity of my lifetime.

It's nice to work on something big that many people recognize and appreciate. I felt this when working at Netflix, and I'd been missing that human connection when I changed jobs. But there are other factors to consider beyond a well-known product: what's my role, who am I doing it with, and what is the compensation?

I ended up having 26 interviews and meetings (of course I kept a log) with various AI tech giants, so I learned a lot about the engineering work they are doing and the engineers who do it. The work itself reminds me of Netflix cloud engineering: huge scale, cloud computing challenges, fast-paced code changes, and freedom for engineers to make an impact. Lots of very interesting engineering problems across the stack. It's not just GPUs, it's everything.

The engineers I met were impressive: the AI giants have been very selective, to the point that I wasn't totally sure I'd pass the interviews myself. Of the companies I talked to, OpenAI had the largest number of talented engineers I already knew, including former Netflix colleagues such as Vadim who was encouraging me to join. At Netflix, Vadim would bring me performance issues and watch over my shoulder as I debugged and fixed them. It's a big plus to have someone at a company who knows you well, knows the work, and thinks you'll be good at the work.

Some people may be excited by what it means for OpenAI to hire me, a well known figure in computer performance, and of course I'd like to do great things. But to be fair on my fellow staff, there are many performance engineers already at OpenAI, including veterans I know from the industry, and they have been busy finding important wins. I'm not the first, I'm just the latest.

Building Orac

AI was also an early dream of mine. As a child I was a fan of British SciFi, including Blake's 7 (1978-1981) which featured a sarcastic, opinionated supercomputer named Orac. Characters could talk to Orac and ask it to do research tasks. Orac could communicate with all other computers in the universe, delegate work to them, and control them (this was very futuristic in 1978, pre-Internet as we know it).

Orac was considered the most valuable thing in the Blake's 7 universe, and by the time I was a university engineering student I wanted to build Orac. So I started developing my own natural language processing software. I didn't get very far, though: main memory at the time wasn't large enough to store an entire dictionary plus metadata. I visited a PC vendor with my requirements and they laughed, telling me to buy a mainframe instead. I realized I needed it to distinguish hot versus cold data and leave cold data on disk, and maybe I should be using a database… and that was about where I left that project.

Last year I started using ChatGPT, and wondered if it knew about Blake's 7 and Orac. So I asked:

ChatGPT's response nails the character. I added it to Settings->Personalization->Custom Instructions, and now it always answers as Orac. I love it. (There's also surprising news for Blake's 7 fans: A reboot was just announced!)

What's next for me

I am now a Member of Technical Staff for OpenAI, working remotely from Sydney, Australia, and reporting to Justin Becker. The team I've joined is ChatGPT performance engineering, and I'll be working with the other performance engineering teams at the company. One of my first projects is a multi-org strategy for improving performance and reducing costs.

There's so many interesting things to work on, things I have done before and things I haven't. I'm already using Codex for more than just coding. Will I be doing more eBPF, Ftrace, PMCs? I'm starting with OpenAI's needs and seeing where that takes me; but given those technologies are proven for finding datacenter performance wins, it seems likely -- I can lead the way. (And if everything I've described here sounds interesting to you, OpenAI is hiring.)

I was at Linux Plumber's Conference in Toyko in December, just after I announced leaving Intel, and dozens of people wanted to know where I was going next and why. I thought I'd write this blog post to answer everyone at once. I also need to finish part 2 of hiring a performance engineering team (it was already drafted before I joined OpenAI). I haven't forgotten.

It took months to wrap up my prior job and start at OpenAI, so I was due for another haircut. I thought it'd be neat to ask Mia about ChatGPT now that I work on it, then realized it had been months and she could have changed her mind. I asked nervously: "Still using ChatGPT?". Mia responded confidently: "twenty-four seven!"

I checked with Mia, she was thrilled to be mentioned in my post. This is also a personal post: no one asked me to write this.

06 Feb 2026 1:00pm GMT

04 Feb 2026

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Dave Airlie (blogspot): nouveau: a tale of two bugs

Just to keep up some blogging content, I'll do where did I spend/waste time last couple of weeks.

I was working on two nouveau kernel bugs in parallel (in between whatever else I was doing).

Bug 1: Lyude, 2 or 3 weeks ago identified the RTX6000 Ada GPU wasn't resuming from suspend. I plugged in my one and indeed it wasn't. Turned out since we moved to 570 firmware, this has been broken. We started digging down various holes on what changed, sent NVIDIA debug traces to decode for us. NVIDIA identified that suspend was actually failing but the result wasn't getting propogated up. At least the opengpu driver was working properly.

I started writing patches for all the various differences between nouveau and opengpu in terms of what we send to the firmware, but none of them were making a difference.

I took a tangent, and decided to try and drop the latest 570.207 firmware into place instead of 570.144. NVIDIA have made attempts to keep the firmware in one stream more ABI stable. 570.207 failed to suspend, but for a different reason.

It turns out GSP RPC messages have two levels of sequence numbering, one on the command queue, and one on the RPC. We weren't filling in the RPC one, and somewhere in the later 570's someone found a reason to care. Now it turned out whenever we boot on 570 firmware we get a bunch of async msgs from GSP, with the word ASSERT in them with no additional info. Looks like at least some of those messages were due to our missing sequence numbers and fixing that stopped those.

And then? still didn't suspend/resume. Dug into memory allocations, framebuffer suspend/resume allocations. Until Milos on discord said you did confirm the INTERNAL_FBSR_INIT packet is the same, and indeed it wasn't. There is a flag bEnteringGCOff, which you set if you are entering into graphics off suspend state, however for normal suspend/resume instead of runtime suspend/resume, we shouldn't tell the firmware we are going to gcoff for some reason. Fixing that fixed suspend/resume.

While I was head down on fixing this, the bug trickled up into a few other places and I had complaints from a laptop vendor and RH internal QA all lined up when I found the fix. The fix is now in drm-misc-fixes.

Bug 2: A while ago Mary, a nouveau developer, enabled larger pages support in the kernel/mesa for nouveau/nvk. This enables a number of cool things like compression and gives good speedups for games. However Mel, another nvk developer reported random page faults running Vulkan CTS with large pages enabled. Mary produced a workaround which would have violated some locking rules, but showed that there was some race in the page table reference counting.

NVIDIA GPUs post pascal, have a concept of a dual page table. At the 64k level you can have two tables, one with 64K entries, and one with 4K entries, and the addresses of both are put in the page directory. The hardware then uses the state of entries in the 64k pages to decide what to do with the 4k entries. nouveau creates these 4k/64k tables dynamically and reference counts them. However the nouveau code was written pre VMBIND, and fully expected the operation ordering to be reference/map/unmap/unreference, and we would always do a complete cycle on 4k before moving to 64k and vice versa. However VMBIND means we delay unrefs to a safe place, which might be after refs happen. Fun things like ref 4k, map 4k, unmap 4k, ref 64k, map 64k, unref 4k, unmap 64k, unref 64k can happen, and the code just wasn't ready to handle those. Unref on 4k would sometimes overwrite the entry in the 64k table to invalid, even when it was valid. This took a lot of thought and 5 or 6 iterations on ideas before we stopped seeing fails. In the end the main things were to reference count the 4k/64k ref/unref separately, but also the last thing to do a map operation owned the 64k entry, which should conform to how userspace uses this interface.

The fixes for this are now in drm-misc-next-fixes.

Thanks to everyone who helped, Lyude/Milos on the suspend/resume, Mary/Mel on the page tables.

04 Feb 2026 9:04pm GMT

22 Jan 2026

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

James Bottomley: Adding Two Factor Authentication to Android (LineageOS)

I really like the idea of using biometrics to add extra security, but have always hated the idea that simply touching the fingerprint sensor would unlock your entire phone, so in my version of LineageOS the touch to unlock feature is disabled but I still use second factor biometrics for the security of various apps. Effectively the android unlock policy is Fingerprint OR PIN/Pattern/Password and I simply want that OR to become an AND.

The problem

The idea of using two factor authentication (2FA) was pioneered by GrapheneOS but since I like the smallness of the Pixel 3 that's not available to me (plus it only seems to work with pin and fingerprint and my preferred unlock is pattern). However, since I build my own LineageOS anyway (so I can sign and secure boot it) I thought I'd look into adding the feature … porting from GrapheneOS should be easy, right? In fact, when looking in the GrapheneOS code for frameworks/base, there are about nine commits adding the feature:

a7a19bf8fb98 add second factor to fingerprint unlock

5dd0e04f82cd add second factor UI

9cc17fd97296 add second factor to FingerprintService

c92a23473f3f add second factor to LockPattern classes

c504b05c933a add second factor to TrustManagerService

0aa7b9ec8408 add second factor to AdaptiveAuthService

62bbdf359687 add second factor to LockSettingsStateListener

7429cc13f971 add second factor to LockSettingsService

6e2d499a37a2 add second factor to DevicePolicyManagerServiceAnd a diffstat of over 3,000 lines … which seems a bit much for changing an OR to an AND. Of course, the reason it's so huge is because they didn't change the OR, they implemented an entirely new bouncer (bouncer being the android term in the code for authorisation gateway) that did pin and fingerprint in addition to the other three bouncers doing pattern, pin and password. So not only would I have to port 3,000 lines of code, but if I want a bouncer doing fingerprint and pattern, I'd have to write it. I mean colour me lazy but that seems way too much work for such an apparently simple change.

Creating a new 2FA unlock

So is it actually easy? The rest of this post documents my quest to find out. Android code itself isn't always easy to read: being Java it's object oriented, but the curse of object orientation is that immediately after you've written the code, you realise you got the object model wrong and it needs to be refactored … then you realise the same thing after the first refactor and so on until you either go insane or give up. Even worse when many people write the code they all end up with slightly different views of what the object model should be. The result is what you see in Android today: model inconsistency and redundancy which get in the way when you try to understand the code flow simply by reading it. One stroke of luck was that there is actually only a single method all of the unlock types other than fingerprint go through KeyguardSecurityContainerController.showNextSecurityScreenOrFinish() with fingerprint unlocking going via a listener to the KeyguardUpdateMonitorCallback.onBiometricAuthenticated(). And, thanks to already disabling fingerprint only unlock, I know that if I simply stop triggering the latter event, it's enough to disable fingerprint only unlock and all remaining authentication goes through the former callback. So to implement the required AND function, I just have to do this and check that a fingerprint authentication is also present in showNext.. (handily signalled by KeyguardUpdateMonitor.userUnlockedWithBiometric()). The latter being set fairly late in the sequence that does the onBiometricAuthenticated() callback (so I have to cut it off after this to prevent fingerprint only unlock). As part of the Android redundancy, there's already a check for fingerprint unlock as its own segment of a big if/else statement in the showNext.. code; it's probably a vestige from a different fingerprint unlock mechanism but I disabled it when the user enables 2FA just in case. There's also an insanely complex set of listeners for updating the messages on the lockscreen to guide the user through unlocking, which I decided not to change (if you enable 2FA, you need to know how to use it). Finally, I diverted the code that would call the onBiometricAuthenticated() and instead routed it to onBiometricDetected() which triggers the LockScreen bouncer to pop up, so now you wake your phone, touch the fingerprint to the back, when authenticated, it pops up the bouncer and you enter your pin/pattern/password … neat (and simple)!

Well, not so fast. While the code above works perfectly if the lockscreen is listening for fingerprints, there are two cases where it doesn't: if the phone is in lockdown or on first boot (because the Android way of not allowing fingerprint only authentication for those cases is not to listen for it). At this stage, my test phone is actually unusable because I can never supply the required fingerprint for 2FA unlocking. Fortunately a rooted adb can update the 2FA in the secure settings service: simply run sqlite3 on /data/system/locksettings.db and flip user_2fa from 1 to 0.

The fingerprint listener is started in KeyguardUpdateMonitor, but it has a fairly huge set of conditions in updateFingerprintListeningState() which is also overloaded by doing detection as well as authentication. In the end it's not as difficult as it looks: shouldListenForFingerprint needs to be true and runDetect needs to be false. However, even then it doesn't actually work (although debugging confirms it's trying to start the fingerprint listening service); after a lot more debugging it turns out that the biometric server process, which runs fingerprint detection and authentication, also has a redundant check for whether the phone is encrypted or in lockdown and refuses to start if it is, which also now needs to return false for 2FA and bingo, it works in all circumstances.

Conclusion

The final diffstat for all of this is

5 files changed, 55 insertions(+), 3 deletions(-)So I'd say that is way simpler than the GrapheneOS one. All that remains is to add a switch for the setting (under the fingerprint settings) in packages/apps/Settings and it's done. If you're brave enough to try this for yourself you can go to my github account and get both the frameworks and settings commits (if you don't want fingerprint unlock disable when 2FA isn't selected, you'll have to remove the head commit in frameworks). I suppose I should also add I've up-ported all of my other security stuff and am now on Android-15 (LineageOS-22.2).

22 Jan 2026 5:17pm GMT

04 Jan 2026

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Pete Zaitcev: The fall of LJ

Great, I am unable to comment at BG.

Theoretically, I have a spare place at Meenuvia, but that platform is also in decline. The owner, Pixy, has no time even to fix the slug problem that cropped up a few months ago (how do you regress a platform that was stable for 20 years, I don't know).

Most likely, I'll give up on blogging entirely, and move to Twitter or Fediverse.

04 Jan 2026 8:32pm GMT

Matthew Garrett: What is a PC compatible?

Wikipedia says "An IBM PC compatible is any personal computer that is hardware- and software-compatible with the IBM Personal Computer (IBM PC) and its subsequent models". But what does this actually mean? The obvious literal interpretation is for a device to be PC compatible, all software originally written for the IBM 5150 must run on it. Is this a reasonable definition? Is it one that any modern hardware can meet?

Before we dig into that, let's go back to the early days of the x86 industry. IBM had launched the PC built almost entirely around off-the-shelf Intel components, and shipped full schematics in the IBM PC Technical Reference Manual. Anyone could buy the same parts from Intel and build a compatible board. They'd still need an operating system, but Microsoft was happy to sell MS-DOS to anyone who'd turn up with money. The only thing stopping people from cloning the entire board was the BIOS, the component that sat between the raw hardware and much of the software running on it. The concept of a BIOS originated in CP/M, an operating system originally written in the 70s for systems based on the Intel 8080. At that point in time there was no meaningful standardisation - systems might use the same CPU but otherwise have entirely different hardware, and any software that made assumptions about the underlying hardware wouldn't run elsewhere. CP/M's BIOS was effectively an abstraction layer, a set of code that could be modified to suit the specific underlying hardware without needing to modify the rest of the OS. As long as applications only called BIOS functions, they didn't need to care about the underlying hardware and would run on all systems that had a working CP/M port.

By 1979, boards based on the 8086, Intel's successor to the 8080, were hitting the market. The 8086 wasn't machine code compatible with the 8080, but 8080 assembly code could be assembled to 8086 instructions to simplify porting old code. Despite this, the 8086 version of CP/M was taking some time to appear, and a company called Seattle Computer Products started producing a new OS closely modelled on CP/M and using the same BIOS abstraction layer concept. When IBM started looking for an OS for their upcoming 8088 (an 8086 with an 8-bit data bus rather than a 16-bit one) based PC, a complicated chain of events resulted in Microsoft paying a one-off fee to Seattle Computer Products, porting their OS to IBM's hardware, and the rest is history.

But one key part of this was that despite what was now MS-DOS existing only to support IBM's hardware, the BIOS abstraction remained, and the BIOS was owned by the hardware vendor - in this case, IBM. One key difference, though, was that while CP/M systems typically included the BIOS on boot media, IBM integrated it into ROM. This meant that MS-DOS floppies didn't include all the code needed to run on a PC - you needed IBM's BIOS. To begin with this wasn't obviously a problem in the US market since, in a way that seems extremely odd from where we are now in history, it wasn't clear that machine code was actually copyrightable. In 1982 Williams v. Artic determined that it could be even if fixed in ROM - this ended up having broader industry impact in Apple v. Franklin and it became clear that clone machines making use of the original vendor's ROM code wasn't going to fly. Anyone wanting to make hardware compatible with the PC was going to have to find another way.

And here's where things diverge somewhat. Compaq famously performed clean-room reverse engineering of the IBM BIOS to produce a functionally equivalent implementation without violating copyright. Other vendors, well, were less fastidious - they came up with BIOS implementations that either implemented a subset of IBM's functionality, or didn't implement all the same behavioural quirks, and compatibility was restricted. In this era several vendors shipped customised versions of MS-DOS that supported different hardware (which you'd think wouldn't be necessary given that's what the BIOS was for, but still), and the set of PC software that would run on their hardware varied wildly. This was the era where vendors even shipped systems based on the Intel 80186, an improved 8086 that was both faster than the 8086 at the same clock speed and was also available at higher clock speeds. Clone vendors saw an opportunity to ship hardware that outperformed the PC, and some of them went for it.

You'd think that IBM would have immediately jumped on this as well, but no - the 80186 integrated many components that were separate chips on 8086 (and 8088) based platforms, but crucially didn't maintain compatibility. As long as everything went via the BIOS this shouldn't have mattered, but there were many cases where going via the BIOS introduced performance overhead or simply didn't offer the functionality that people wanted, and since this was the era of single-user operating systems with no memory protection, there was nothing stopping developers from just hitting the hardware directly to get what they wanted. Changing the underlying hardware would break them.

And that's what happened. IBM was the biggest player, so people targeted IBM's platform. When BIOS interfaces weren't sufficient they hit the hardware directly - and even if they weren't doing that, they'd end up depending on behavioural quirks of IBM's BIOS implementation. The market for DOS-compatible but not PC-compatible mostly vanished, although there were notable exceptions - in Japan the PC-98 platform achieved significant success, largely as a result of the Japanese market being pretty distinct from the rest of the world at that point in time, but also because it actually handled Japanese at a point where the PC platform was basically restricted to ASCII or minor variants thereof.

So, things remained fairly stable for some time. Underlying hardware changed - the 80286 introduced the ability to access more than a megabyte of address space and would promptly have broken a bunch of things except IBM came up with an utterly terrifying hack that bit me back in 2009, and which ended up sufficiently codified into Intel design that it was one mechanism for breaking the original XBox security. The first 286 PC even introduced a new keyboard controller that supported better keyboards but which remained backwards compatible with the original PC to avoid breaking software. Even when IBM launched the PS/2, the first significant rearchitecture of the PC platform with a brand new expansion bus and associated patents to prevent people cloning it without paying off IBM, they made sure that all the hardware was backwards compatible. For decades, PC compatibility meant not only supporting the officially supported interfaces, it meant supporting the underlying hardware. This is what made it possible to ship install media that was expected to work on any PC, even if you'd need some additional media for hardware-specific drivers. It's something that still distinguishes the PC market from the ARM desktop market. But it's not as true as it used to be, and it's interesting to think about whether it ever was as true as people thought.

Let's take an extreme case. If I buy a modern laptop, can I run 1981-era DOS on it? The answer is clearly no. First, modern systems largely don't implement the legacy BIOS. The entire abstraction layer that DOS relies on isn't there, having been replaced with UEFI. When UEFI first appeared it generally shipped with a Compatibility Services Module, a layer that would translate BIOS interrupts into UEFI calls, allowing vendors to ship hardware with more modern firmware and drivers without having to duplicate them to support older operating systems1. Is this system PC compatible? By the strictest of definitions, no.

Ok. But the hardware is broadly the same, right? There's projects like CSMWrap that allow a CSM to be implemented on top of stock UEFI, so everything that hits BIOS should work just fine. And well yes, assuming they implement the BIOS interfaces fully, anything using the BIOS interfaces will be happy. But what about stuff that doesn't? Old software is going to expect that my Sound Blaster is going to be on a limited set of IRQs and is going to assume that it's going to be able to install its own interrupt handler and ACK those on the interrupt controller itself and that's really not going to work when you have a PCI card that's been mapped onto some APIC vector, and also if your keyboard is attached via USB or SPI then reading it via the CSM will work (because it's calling into UEFI to get the actual data) but trying to read the keyboard controller directly won't2, so you're still actually relying on the firmware to do the right thing but it's not, because the average person who wants to run DOS on a modern computer owns three fursuits and some knee length socks and while you are important and vital and I love you all you're not enough to actually convince a transglobal megacorp to flip the bit in the chipset that makes all this old stuff work.

But imagine you are, or imagine you're the sort of person who (like me) thinks writing their own firmware for their weird Chinese Thinkpad knockoff motherboard is a good and sensible use of their time - can you make this work fully? Haha no of course not. Yes, you can probably make sure that the PCI Sound Blaster that's plugged into a Thunderbolt dock has interrupt routing to something that is absolutely no longer an 8259 but is pretending to be so you can just handle IRQ 5 yourself, and you can probably still even write some SMM code that will make your keyboard work, but what about the corner cases? What if you're trying to run something built with IBM Pascal 1.0? There's a risk that it'll assume that trying to access an address just over 1MB will give it the data stored just above 0, and now it'll break. It'd work fine on an actual PC, and it won't work here, so are we PC compatible?

That's a very interesting abstract question and I'm going to entirely ignore it. Let's talk about PC graphics3. The original PC shipped with two different optional graphics cards - the Monochrome Display Adapter and the Color Graphics Adapter. If you wanted to run games you were doing it on CGA, because MDA had no mechanism to address individual pixels so you could only render full characters. So, even on the original PC, there was software that would run on some hardware but not on other hardware.

Things got worse from there. CGA was, to put it mildly, shit. Even IBM knew this - in 1984 they launched the PCjr, intended to make the PC platform more attractive to home users. As well as maybe the worst keyboard ever to be associated with the IBM brand, IBM added some new video modes that allowed displaying more than 4 colours on screen at once4, and software that depended on that wouldn't display correctly on an original PC. Of course, because the PCjr was a complete commercial failure, it wouldn't display correctly on any future PCs either. This is going to become a theme.

There's never been a properly specified PC graphics platform. BIOS support for advanced graphics modes5 ended up specified by VESA rather than IBM, and even then getting good performance involved hitting hardware directly. It wasn't until Microsoft specced DirectX that anything was broadly usable even if you limited yourself to Microsoft platforms, and this was an OS-level API rather than a hardware one. If you stick to BIOS interfaces then CGA-era code will work fine on graphics hardware produced up until the 20-teens, but if you were trying to hit CGA hardware registers directly then you're going to have a bad time. This isn't even a new thing - even if we restrict ourselves to the authentic IBM PC range (and ignore the PCjr), by the time we get to the Enhanced Graphics Adapter we're not entirely CGA compatible. Is an IBM PC/AT with EGA PC compatible? You'd likely say "yes", but there's software written for the original PC that won't work there.

And, well, let's go even more basic. The original PC had a well defined CPU frequency and a well defined CPU that would take a well defined number of cycles to execute any given instruction. People could write software that depended on that. When CPUs got faster, some software broke. This resulted in systems with a Turbo Button - a button that would drop the clock rate to something approximating the original PC so stuff would stop breaking. It's fine, we'd later end up with Windows crashing on fast machines because hardware details will absolutely bleed through.

So, what's a PC compatible? No modern PC will run the DOS that the original PC ran. If you try hard enough you can get it into a state where it'll run most old software, as long as it doesn't have assumptions about memory segmentation or your CPU or want to talk to your GPU directly. And even then it'll potentially be unusable or crash because time is hard.

The truth is that there's no way we can technically describe a PC Compatible now - or, honestly, ever. If you sent a modern PC back to 1981 the media would be amazed and also point out that it didn't run Flight Simulator. "PC Compatible" is a socially defined construct, just like "Woman". We can get hung up on the details or we can just chill.

-

Windows 7 is entirely happy to boot on UEFI systems except that it relies on being able to use a BIOS call to set the video mode during boot, which has resulted in things like UEFISeven to make that work on modern systems that don't provide BIOS compatibility ↩︎

-

Back in the 90s and early 2000s operating systems didn't necessarily have native drivers for USB input devices, so there was hardware support for trapping OS accesses to the keyboard controller and redirecting that into System Management Mode where some software that was invisible to the OS would speak to the USB controller and then fake a response anyway that's how I made a laptop that could boot unmodified MacOS X ↩︎

-

(my name will not be Wolfwings Shadowflight) ↩︎

-

Yes yes ok 8088 MPH demonstrates that if you really want to you can do better than that on CGA ↩︎

-

and by advanced we're still talking about the 90s, don't get excited ↩︎

04 Jan 2026 3:11am GMT

02 Jan 2026

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Greg Kroah-Hartman: Linux kernel security work

Lots of the CVE world seems to focus on "security bugs" but I've found that it is not all that well known exactly how the Linux kernel security process works. I gave a talk about this back in 2023 and at other conferences since then, attempting to explain how it works, but I also thought it would be good to explain this all in writing as it is required to know this when trying to understand how the Linux kernel CNA issues CVEs.

02 Jan 2026 12:00am GMT

16 Dec 2025

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Linux Plumbers Conference: Video recordings are available

We are glad to announce that video recordings of the talks are available on our YouTube channel.

You can use the complete conference playlist or look for "video" links in each contribution in the schedule

16 Dec 2025 5:35am GMT

15 Dec 2025

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Greg Kroah-Hartman: Tracking kernel commits across branches

With all of the different Linux kernel stable releases happening (at least 1 stable branch and multiple longterm branches are active at any one point in time), keeping track of what commits are already applied to what branch, and what branch specific fixes should be applied to, can quickly get to be a very complex task if you attempt to do this manually. So I've created some tools to help make my life easier when doing the stable kernel maintenance work, which ended up making the work of tracking CVEs much simpler to manage in an automated way.

15 Dec 2025 12:00am GMT

14 Dec 2025

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

James Morris: Ultraviolet Linux Talk at Linux Plumbers Conf 2025

I presented an overview of the Ultraviolet Linux (UV) project at Linux Plumbers Conference (LPC) 2025.

UV is a proposed architecture and reference implementation for generalized code integrity in Linux. The goal of the presentation was to seek early feedback from the community and to invite collaboration - it's at an early stage of development currently.

A copy of the slides may be found here (pdf).

14 Dec 2025 3:38am GMT

09 Dec 2025

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Greg Kroah-Hartman: Linux kernel version numbers

Despite having a stable release model and cadence since December 2003, Linux kernel version numbers seem to baffle and confuse those that run across them, causing numerous groups to mistakenly make versioning statements that are flat out false. So let's go into how this all works in detail.

09 Dec 2025 12:00am GMT

08 Dec 2025

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Greg Kroah-Hartman: Linux CVEs, more than you ever wanted to know

It's been almost 2 full years since Linux became a CNA (Certificate Numbering Authority) which meant that we (i.e. the kernel.org community) are now responsible for issuing all CVEs for the Linux kernel. During this time, we've become one of the largest creators of CVEs by quantity, going from nothing to number 3 in 2024 to number 1 in 2025. Naturally, this has caused some questions about how we are both doing all of this work, and how people can keep track of it.

08 Dec 2025 12:00am GMT

04 Dec 2025

Kernel Planet

Kernel Planet

Brendan Gregg: Leaving Intel

I've resigned from Intel and accepted a new opportunity. If you are an Intel employee, you might have seen my fairly long email that summarized what I did in my 3.5 years. Much of this is public:

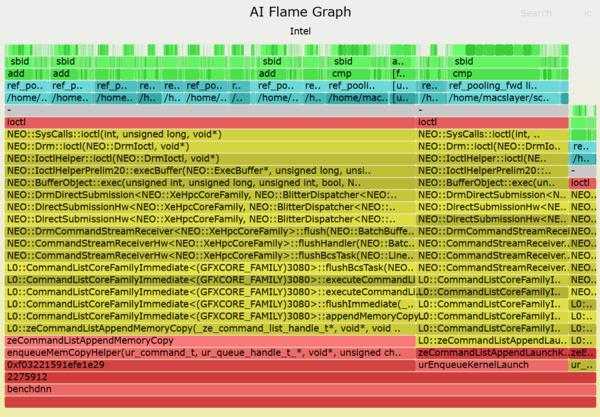

- AI flame graphs and released them as open source

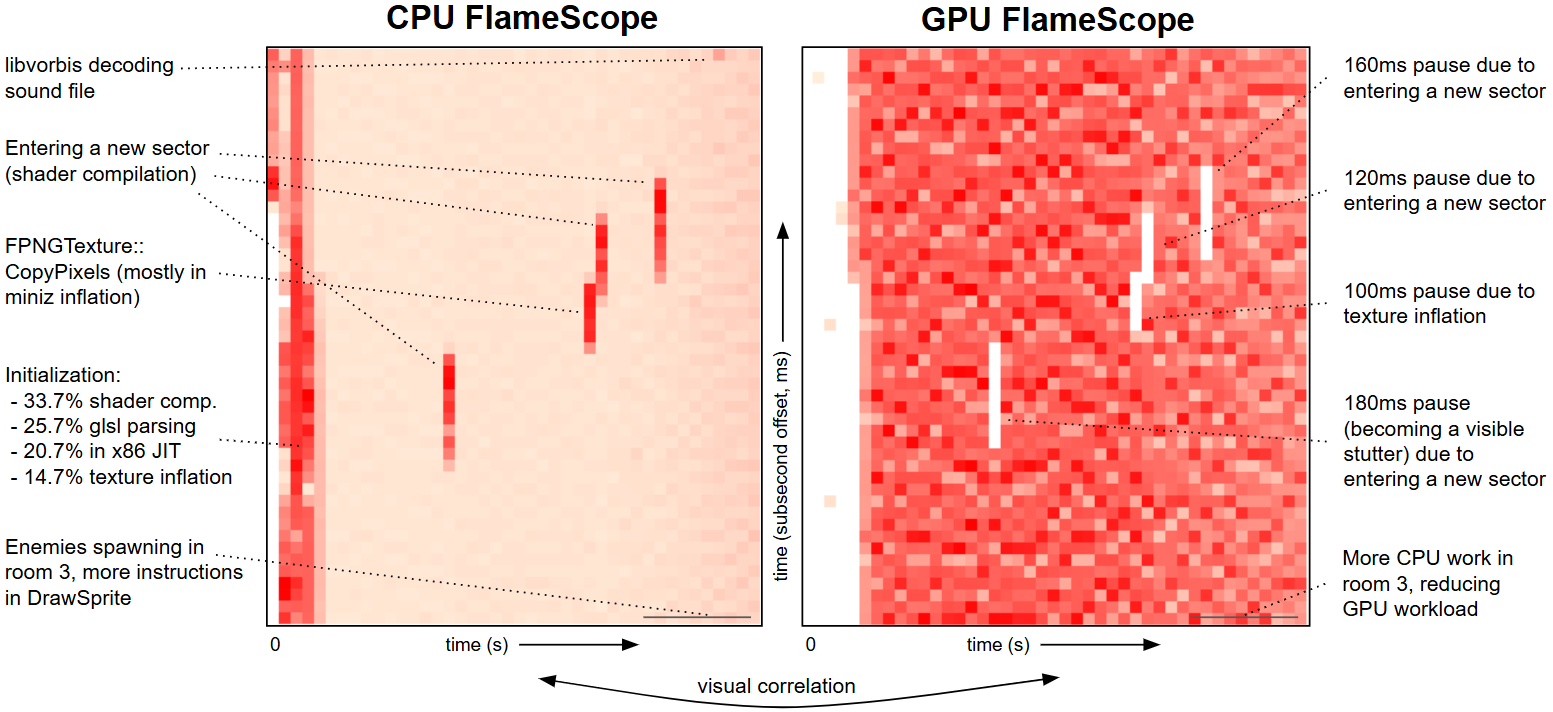

- GPU subsecond-offset heatmap

- Worked with Linux distros to enable stack walking

- Was interviewed by the WSJ about eBPF for security monitoring

- Provided leadership on the eBPF Technical Steering Committee (BSC)

- Co-chaired USENIX SREcon APAC 2023

- Gave 6 conference keynotes

It's still early days for AI flame graphs. Right now when I browse CPU performance case studies on the Internet, I'll often see a CPU flame graph as part of the analysis. We're a long way from that kind of adoption for GPUs (and it doesn't help that our open source version is Intel only), but I think as GPU code becomes more complex, with more layers, the need for AI flame graphs will keep increasing.

I also supported cloud computing, participating in 110 customer meetings, and created a company-wide strategy to win back the cloud with 33 specific recommendations, in collaboration with others across 6 organizations. It is some of my best work and features a visual map of interactions between all 19 relevant teams, described by Intel long-timers as the first time they have ever seen such a cross-company map. (This strategy, summarized in a slide deck, is internal only.)

I always wish I did more, in any job, but I'm glad to have contributed this much especially given the context: I overlapped with Intel's toughest 3 years in history, and I had a hiring freeze for my first 15 months.

My fond memories from Intel include meeting Linus at an Intel event who said "everyone is using fleme graphs these days" (Finnish accent), meeting Pat Gelsinger who knew about my work and introduced me to everyone at an exec all hands, surfing lessons at an Intel Australia and HP offsite (mp4), and meeting Harshad Sane (Intel cloud support engineer) who helped me when I was at Netflix and now has joined Netflix himself -- we've swapped ends of the meeting table. I also enjoyed meeting Intel's hardware fellows and senior fellows who were happy to help me understand processor internals. (Unrelated to Intel, but if you're a Who fan like me, I recently met some other people as well!)

My next few years at Intel would have focused on execution of those 33 recommendations, which Intel can continue to do in my absence. Most of my recommendations aren't easy, however, and require accepting change, ELT/CEO approval, and multiple quarters of investment. I won't be there to push them, but other employees can (my CloudTeams strategy is in the inbox of various ELT, and in a shared folder with all my presentations, code, and weekly status reports). This work will hopefully live on and keep making Intel stronger. Good luck.

04 Dec 2025 1:00pm GMT